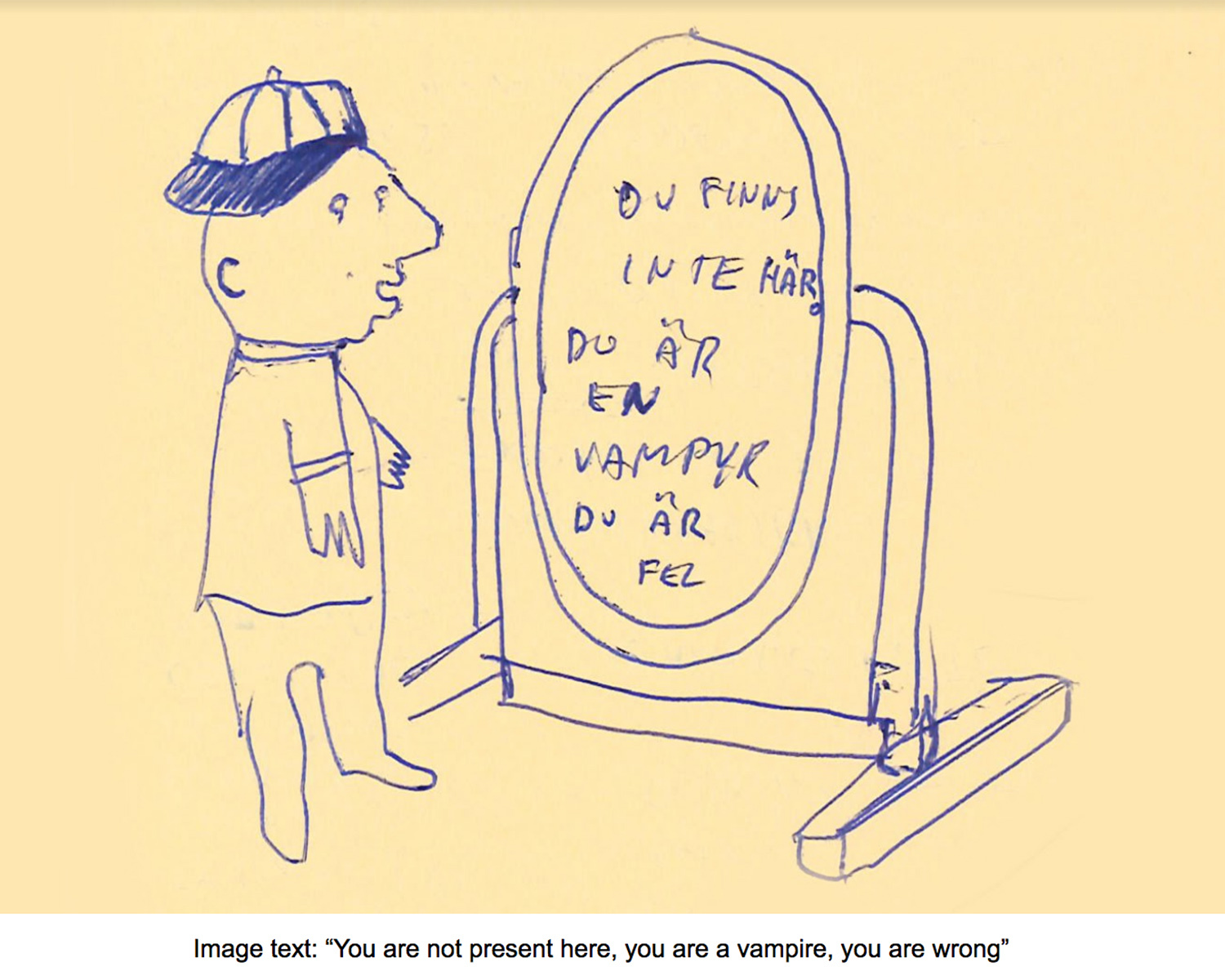

“When those who have the power to name and to socially construct reality choose not to see you or hear you… when someone with the authority of a teacher, say, describes the world and you are not in it, there is a moment of psychic disequilibrium, as if you looked in the mirror and saw nothing. It takes some strength of soul — and not just individual strength, but collective understanding — to resist this void, this non-being, into which you are thrust, and to stand up, demanding to be seen and heard.”

(Adrienne Rich, Blood, Bread, and Poetry: Selected Prose, 1979-1985)

Intro

This text’s purpose is creating understanding for people who don’t necessarily fit into the normalised world of a classroom It aims to generate literacy on the issues faced by transgender and gender non-conforming students and staff in educational settings. We observe a lack of such knowledge in the European higher education institutions of which we are (or were) part. We also identify a lack of staff that are gender diverse (or feel confident being identified as gender diverse), which would enable students to recognise themselves and be inspired.

This text is for people who are curious about inclusive classrooms. It is written for those who are already allies and for those who wish to become allies, who seek to educate themselves and need resources in order to educate others. In short it is addressed to students, teachers, administrators, cleaners, technicians and managers alike, at all those who together build institutions. The text is collectively written and edited by the “Who is in the classroom?” working group, in the framework of the EU-funded collective research and study programme Teaching to Transgress Toolbox (2019–22).

In the following, we will share contexts, experiments, discussions, as well as hands-on guidance material. This includes how to introduce and instigate pronoun and access go-rounds in classrooms, which ensure everybody present is seen and supported in their needs. In this research we focus particularly on the needs of people that are atypical, those of trans*persons and people with mental health problems or visible and invisible impairments.1

As a multilingual (Swedish, French, German, English) working group, we chose to write our reflections in English, whereas the hands-on guidance material, the handout, is translated into Swedish and French in order to be downloaded, printed and used in local contexts. Some of the experiences, proposals and recommendations are linked to specific contexts, but they are adaptable. We acknowledge that sometimes trans*rights or disability rights are not understood as urgent, yet we try to provide guidance in these cases.

- Download Guide, English, PDF 24 pages

- Download Guide, Swedish, PDF 24 pages

- Download Guide, French, PDF 24 pages

Our methods

Our research methods for this piece vary: we have drawn on our own experiences in a range of places (supportive activist contexts). We experimented hands-on with facilitating and participating in go-rounds during the first TTTT workshop week “How to say it” in Brussels (January 2020). We followed the debate between Dean Spade and Jen Manion about the advantages and disadvantages of doing pronoun go-rounds 8 and we consulted the vast range of material available such as manuals and guides (see “References & Resources”).

We connected to friends and people who do not identify with the pronoun they were assigned at birth. We reached out to networks with experience of trans* practices and of changing pronouns, as well as to people with access needs and/or mental health problems. With some of them we recorded conversations that significantly helped us to understand the complexities and to gain practical knowledge on what might work and what might be problematic when teachers do go-rounds in their classrooms.9 You’ll find snippets of the recorded conversations inserted in the following text. We have edited some of the interviews for you to listen and watch in their entirety. Others are not published at the request of the interviewees.

Important to keep in mind: tools are situated

With the TTTT programme we are trying to create accessible knowledge and resources to practice critical pedagogy in the arts. Our aim is to develop tools for dealing with complex and conflicted situations and with the structural problems of the educational institutions of which we are part, be it as students, teachers or administrators.

The ttttoolbox.net homepage states: “Critical intersectional feminist pedagogies [...] provide valuable conceptual and practical tools with which to focus on inclusivity”. However, in a public event titled Engaged Pedagogy that TTTToolbox organized during the first workshop week in Brussels in January 2020, Nassira Hedjerassi from the Institut bell hooks - Paulo Freire in Paris pointed towards the for her problematic term “toolbox” in the title of the project. Nassira said: “I’m not comfortable with tools, even if it is the name of this project [...] it is not the tools [...] the key is the process of questioning our practice all the time [...] no tools, no recipe, just practice [...] and reflecting on our practice all the time.”

Nassira Hedjerassi (bell hooks institute, Paris): “I’m not comfortable with tools”.

Nassira critiques the zeitgeist term “tools”, which suggests it is all about inventing something to solve our problems, when rather it is us who must do the work to change problematic environments (“praxis” = practice and reflection). There must be feedback throughout the process of implementing a tool in order to re-evaluate the impact of the tool on the environment in which it is being used.

Is it really enough to create tools? Isn’t the human value system shifting toward a right-wing, racist and patriarchal one? And how and for what purpose might the tools we provide on this website be used in such a hateful culture? How can we prevent our tools from being used for the “pinkwashing” of institutions, while processes of oppression still continue under the surface?

This means we cannot just do some go-rounds in the classroom and say “everything is solved”. Practice means experimenting with modes of doing things, evaluating how it went, adjusting and trying again. It can be the start of collectively and critically reflecting on what’s going on in learning situations.

Practice is also always contextual to and contingent on the people involved. Therefore we would like to introduce the members of our working group before using the “we”.

I am a trans*dyke who grew up in France, with dyscalculia. I have light skin and also the experience of a non-white household. I never really understood school but at the same time it was an escape from my household, which was sometimes toxic. I am now in a French art school and see the limits of the pedagogy there but I enjoy the “hands-on” approach to learning.

I am a multiple and grew up in a middle class household in a pretty monocultural, white, Catholic environment in post-war Germany. I strongly felt the oppressions and exclusions connected to the unified “we”.

I am a gender-queer, flexi-presenting, all-genital loving, pan-romantic person. A white cis-heteronormative middle class environment made me and the processes of its normative societal enforcements angered me.

I am cis-male artist and researcher. I grew up in a Swedish rural working class family in which neurodivergence and mental health problems were and are present. Because of my non-normal body and personality I experience social and structural oppressions.

The go-round as a tool to create a safe(r) space is mostly used in activist environments, where people share common goals and sensibilities. Therefore, separating a contingent and situated tool from the activist context and applying it universally across different contexts has potential to become problematic. Classrooms accommodate many different people with different interests, backgrounds, opinions and goals. Ostensibly, the only commonality in the classroom is the fact that the students are in the same year, class or course. There is also a difference between a university course, where people meet around a certain field or discipline and a classroom at a primary or secondary school, where mandatory schooling brings a range of pupils together to form a group.

Seen as a mere tool, the go-round, just like a chainsaw or a scalpel, can be really effective and it can also be dangerous. It depends on who uses it, how it is being used, where, when and why. Therefore we suggest that you view this material as a tool that comes with a driver's license. With the following we hope to provide guidance concerning some important teachings and practices. We will also direct you to a range of other resources and to support organisations.

Glossary

As a reading aid for this multimodal piece (text, recordings, images) we wanted to share this great glossary (English). It has been put together by the folks at Straight for Equality, an outreach and education programme in the United States helping allies understand their role in supporting and advocating for LGBTQI+ people. The glossary might be helpful to get a better understanding of the vocabulary we use in the following text and to create deeper insight and understanding of trans* and non-binary issues more generally. 2

For a glossary explaining gender and trans* vocabulary in Swedish, see Swedish trans organisation Transformering, Ordlista. and RFSL’s glossary Begrepsordlista.

For a French vocabulary of trans*identities, see the short glossary Lexique created by the French transfeminist association “Outrans”.

Don’t assume

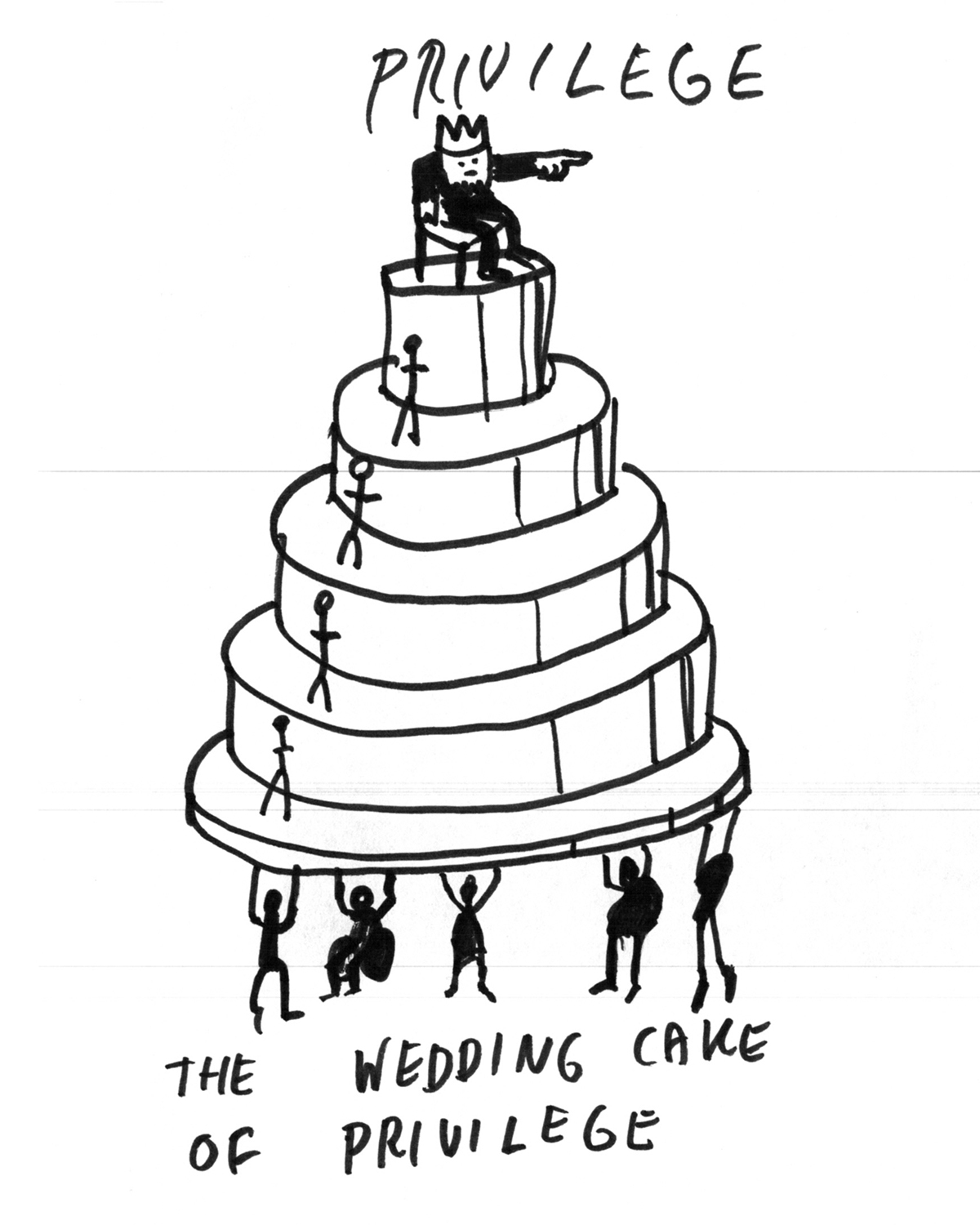

We need to begin with privilege

“From the top where you are, it is really difficult to see the rows behind you.” (Sja'iesta Badloe in the Dazed film “Wypipo” with Mykki Blanco, 2018)

Imagine we are sitting in a cinema watching a movie. The ones sitting in the front rows seldom know what the view from the rear rows is, because the view at the front is good for them. It is interesting that when we assume, we tend to only assume things we know or have experienced before. If during our upbringing we were never introduced to experiences and identities that differ from our own, for example, in terms of ethnicity, cultural background, disability, sexuality, gender identity, economic situation, and so on, it tends to be hard to imagine the challenges that might come with those experiences and identities.

MC Coble, Nika Dahlberg-Melin, Eva Weinmayr. Clip: “Learning to unlearn”10

Things are not always as they seem

We do go-rounds because we want to understand who is in the room with us without assuming. We learned that we cannot assume what someone’s needs are by looking at them – especially if these assumptions come from a cis-hetero 3, patriarchal 4, white 5, ableist 6, classist 7 perspective. The go-round is a tool for trying to reduce some of the impact of projections and assumptions. It is not perfect, but as Dean Spade (2018) says:

“The thing about the pronoun go-round is that it is not meant to and cannot take care of all the many complex problems of judgment, identity and anxiety that exist around our complex lives and our political movements. It is merely an attempt to create a practice of not assuming we know what someone goes by just by looking at them.”

The problem is the fact that people, and we as people, assume. We as people because all of us play a part in this violent narrative of assuming – in whichever manner the assumption takes place. One way to tackle assumptions and bring practices of care into the classroom is go-rounds.

A question of care

Practicing not assuming is a question of care. Care, it could be said, is about trying to meet the needs of somebody else in order to prevent harm and suffering and allow them to flourish.11 According to Melanie Joy, the topic of care, or caring for each other, is not something that has always been a priority in classrooms or curricula. She says we are taught a bunch of things in school but that we rarely learn to care for each other (Joy 2013). If we don’t see or experience care from teachers how can we implement such practices in our own lives? From the perspective of a teacher, however, caring about student wellbeing is often an emotional labour that is undervalued and overlooked and often leads to exhaustion.12

As an atypical person I often experience the university as a stressful and emotionally cold place. It takes so little, only a few words or the recognition from a teacher letting me know that they see me and my struggles, to make everything shift in a positive direction.

Giving and receiving care

Care is often understood in terms of who most needs it or what is most needed. The feminist project looks at the ethics of care and recognises the complex interpersonal and collective nature of the relational. Care, here, becomes an exchange of acts that are not necessarily based on need but rather on an awareness, desire and collective understanding of what it means to “meet” each other. Intersectional ethics of care conceives bodies in their different abilities and disabilities, in their ability to give and to receive care. Caring should not be explored through an ableist hierarchy of who can give care (physically or mentally) to whom but rather how care is or can be exchanged, supported and encouraged beyond the realm of need. Care is not a one-way street. It comprises both needs-based care and interpersonal and interdependent relations.13

Through my work as a care-worker, where I assist a person living with disabilities, I myself am cared for in such a way that I have never before experienced in a working environment. My employer and her husband, who both rely on personal assistance, have a valuable and deep understanding of the complex and multifaceted ethics of care. Their extensive dealings with receiving and providing care makes their ethics and application of care revolutionary.

What are we talking about when we talk about care in the context of education, the arts, the classroom, pedagogy?

Are we talking about listening and mindfulness as acts of care?

Are we talking about accessibility as an act of care?

Are we talking about caring for one another?

Are we talking about what politics are at play and who is talking about the labour of care?

Are we talking about how female socialisation is premised on emotional labour?

Are we talking about making sure that the emotional labour of minorities is not exploited?

Are we talking about the distribution of labour and tasks in working groups?

These are some of the questions that you can ask of yourself and your environment. A good way to begin understanding the ethics of care in the classroom is to evaluate how a group works. For example it can be good to ask, who tends to organise, who tends to volunteer, who is inclined to talk a lot, and who seems to remain quiet? Introducing the concept of care into the classroom can help people to understand their roles in the group and just taking time for everyone to share their experience could improve the general atmosphere.

Taking care of others can be a lot of work and more often than not this physical and emotional labour is expected of a certain class or group of people. It is important to work towards an equal distribution of care within groups and not to rely on certain people to guarantee the care. It’s a big responsibility that needs to be constantly re-evaluated. In the context of a classroom it might be good to actively decide what type of care we want to practice and build within the group and how to distribute it – keeping in mind that some might be very vocal about their needs and others might not be familiar with sharing their needs or are uncomfortable with doing so.

Access and accessibility

Access go-round: What do people need to access the space and each other?

An access go-round is the act of taking time and asking participants of the group (any group) about their access needs. When we talk about access needs we need to approach it from a non-able-bodied perspective. We need to decentralise internalised ableism by constantly checking ourselves on our differently-abled and disabled bodied privileges, particularly in a world built first and foremost for enabled bodies and minds. To talk about access in this context is a complex exercise, and we will address a range of different approaches in what follows.

Access needs

An access need could be that somebody has hearing difficulties. Once people in the room learn about these difficulties they can speak louder. It could be that somebody has difficulties sitting still during the class. Once others know about this more breaks can be planned for students to get up and stretch their legs, or physical exercises may be proposed. Your needs might be normative, such as toilet breaks, internet access and a good night’s sleep, or you might be on the atypical part of the spectrum and have needs connected to dyslexia, being hard of hearing or a wheelchair user, having ADHD or food allergies. You may have access needs related to a language barrier. Your access needs may also change depending on the psychosocial environment, in relation to the group of people you are with or the physical environment.

During our one-week TTTT workshop in Brussels it turned out that some of the French speakers had access needs in terms of understanding the English language. Once the group understood this, we set up a space in the room where the discussions were temporarily live -translated into French.

If we consider access needs as a technicality to be met for a better collective experience rather than a way to point out our differences, we can begin to approach needs from an equitable standpoint. This means everyone departs from their needs either being met or not being met.

Access empathy

Even when we try, access is not always possible, since we live in an ableist world with predominantly ableist infrastructures. Here, genuine intent, understanding of access needs and empathy help a lot. Sometimes it means asking what actual needs someone has before, during and after the event – so that next time you can be better prepared and more aware. Sometimes it means just being available when there isn’t access and to understand and acknowledge this lack. Mia Mingus, a writer, educator and trainer for transformative justice and disability justice, calls this empathy “access intimacy”. It “is that elusive, hard to describe feeling when someone else ’gets’ your access needs. [...] Sometimes access intimacy doesn’t even mean that everything is 100% accessible.” (Mingus, 2011)

Checklist of access points 14

It might be helpful to follow a checklist of access points. Is there an elevator? Is there toilet access? Is the space easy to get to? How to set up the seating area in ways that improve accessibility? Our interviewees Håkan and Tori explained, for instance, that the idea of the designated wheelchair spot can be quite alienating. A more equal access for wheelchair users could mean having the opportunity to choose their own seating arrangement. However, for some it might be a stressful experience to enter a space without predetermined seating. Therefore, it becomes important to allow the space to be negotiated amongst the different access needs people might have.

Pronoun go-round

What is it and why is it important?

A pronoun go-round is the act of taking time and asking participants of the group (any group) to state which pronoun they want other people to use when referring to them, and which name they go by. For example, “I am Flo*Souad and I go by they”. It’s as simple as that.

MC Coble, Nika Dahlberg-Melin, Eva Weinmayr. Clip: “As a teacher you need to take responsibility”

In group settings such as classrooms, a pronoun go-round can be held by asking participants to introduce themselves one by one. Doing a pronoun go-round can help to create “access” to each other. The pronoun go-round facilitates relations and sometimes enables students to be able to communicate at all.

MC Coble, Nika Dahlberg-Melin, Eva Weinmayr. Clip: “That’s not stuff I’ve always known or felt”

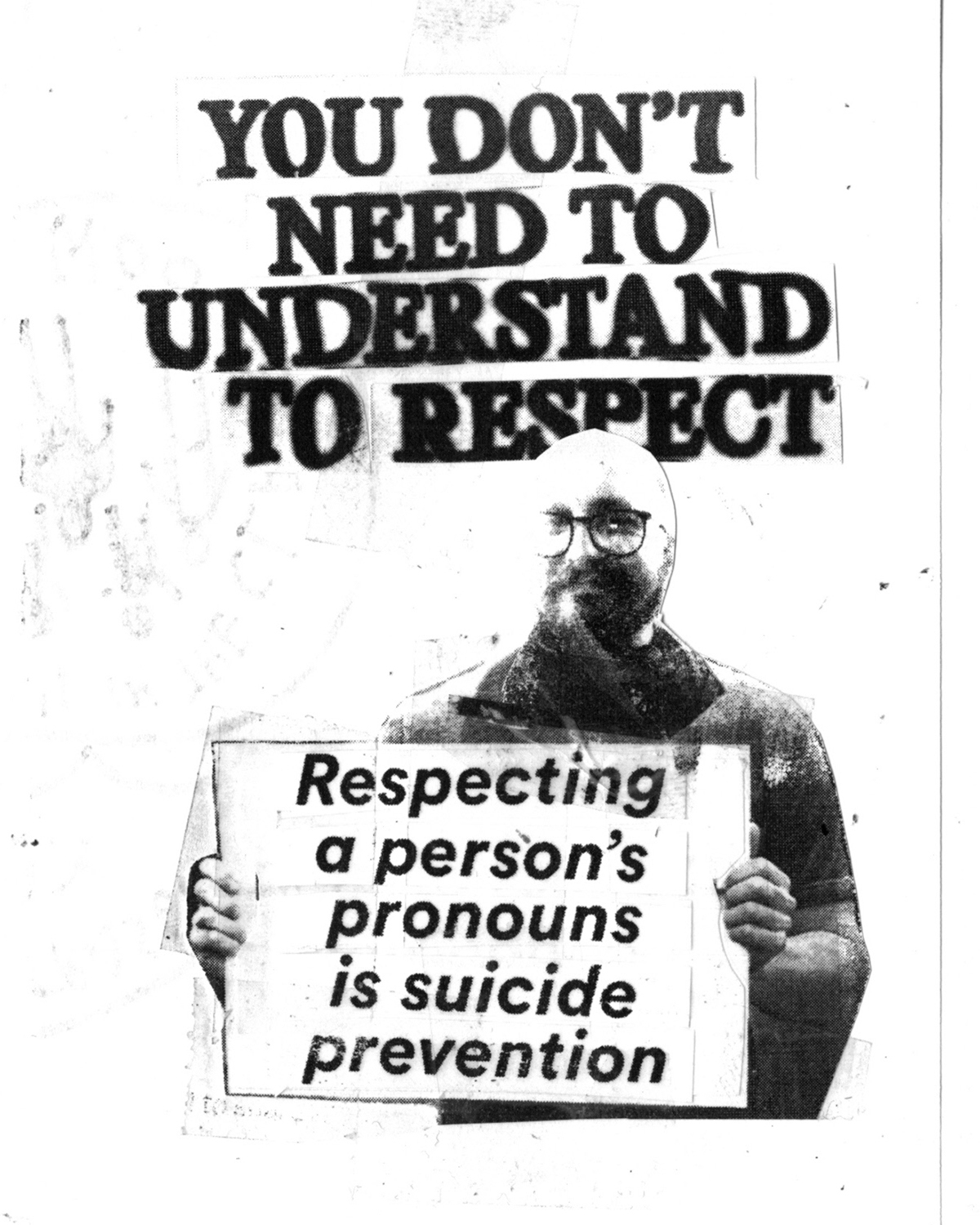

“One way to understand the importance of pronoun go-rounds”, says Nika “has to do with the emotional experience when you are misgendered.” She explains, for example, that being misgendered can make her mind circle around the question of how to deal with the situation and when this happens she’s not capable to participate in the content of the meeting. Nika stresses that being trans or having mental health problems is like “having two jobs at once”. You have to do your actual work in the meeting, but at the same time educate other people and find alternative ways of working together that make it possible for you to function in that situation.

MC Coble, Nika Dahlberg-Melin, Eva Weinmayr. Clip: “Why is it so important?”

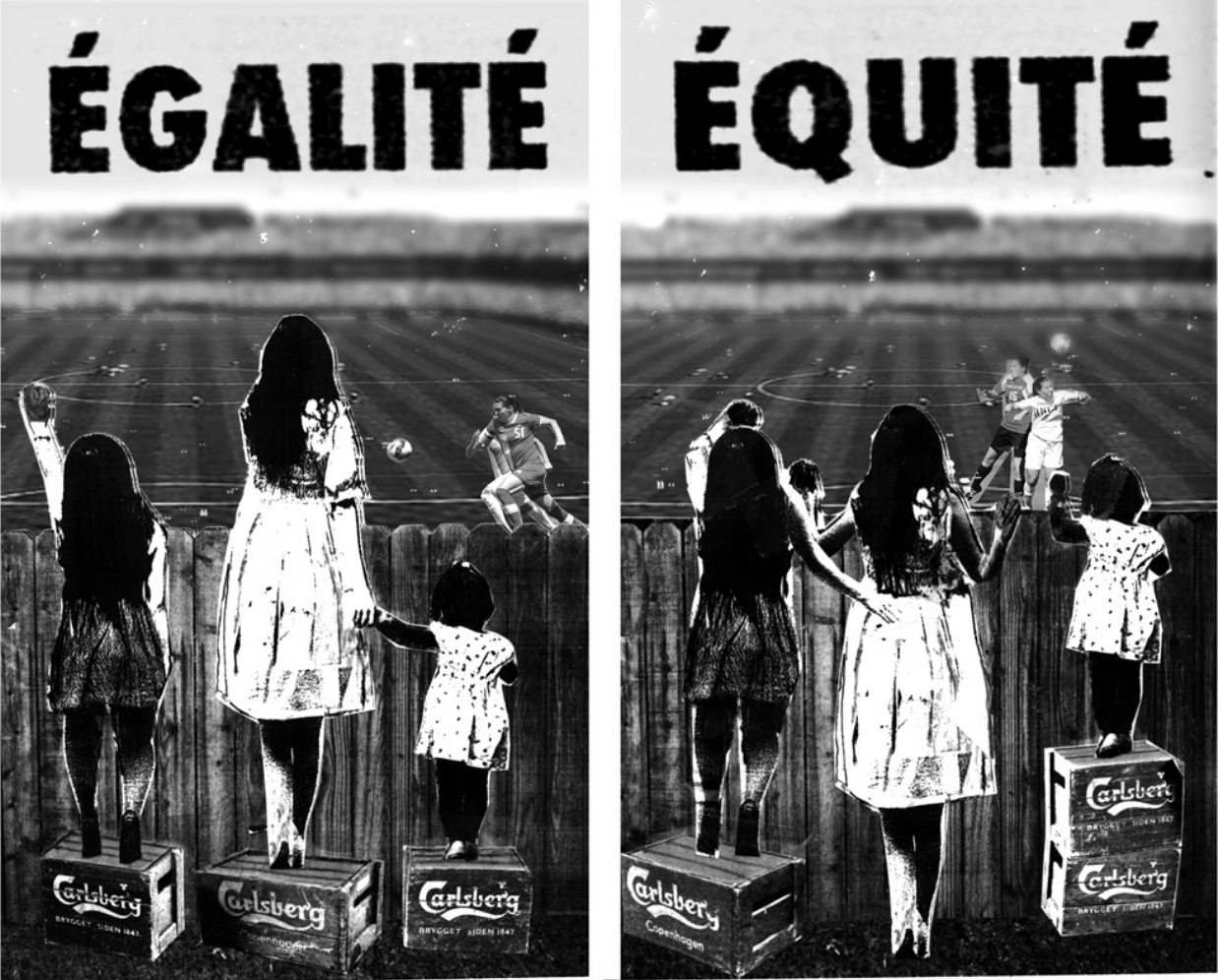

It is important to understand that the “freedom” to choose the pronoun implies different things for different people depending on their needs. We are not referring here to freedom as it is understood within the logic of social equality – meaning that everybody has equal rights from the start. We relate these questions to the concept of social equity that puts emphasis on whether something results in a fair outcome.15 For example, if someone needs to be addressed with their correct pronoun to be able to participate (and not to be forced to leave the space), then we care for that need. In the same logic, when a cis person decides that they want to be called “the master” or “the cow” (see clip below) highlighting their privilege by mocking the importance of pronouns for some, we must recognise that these are not needs to be cared for. We must be able to address the kind of oppression that might be taking place similarly to how we would address sexist, ableist or racist oppression.

MC Coble, Nika Dahlberg-Melin, Eva Weinmayr. Clip: “A proper introduction is crucial”

Facilitating a pronoun go-round

“Pronoun go-rounds can be useful when people know why they are doing them and what they are doing.” Dean Spade (2018) describes how important it is to inform people about why we are doing the pronoun go-round, what pronouns mean and their importance in trans*inclusion. In situations where the pronoun go-round is not properly introduced, it can cause confusion and unease in the group that might lead people to joke and thereby unintentionally reproduce oppression and unequal access to the classroom.

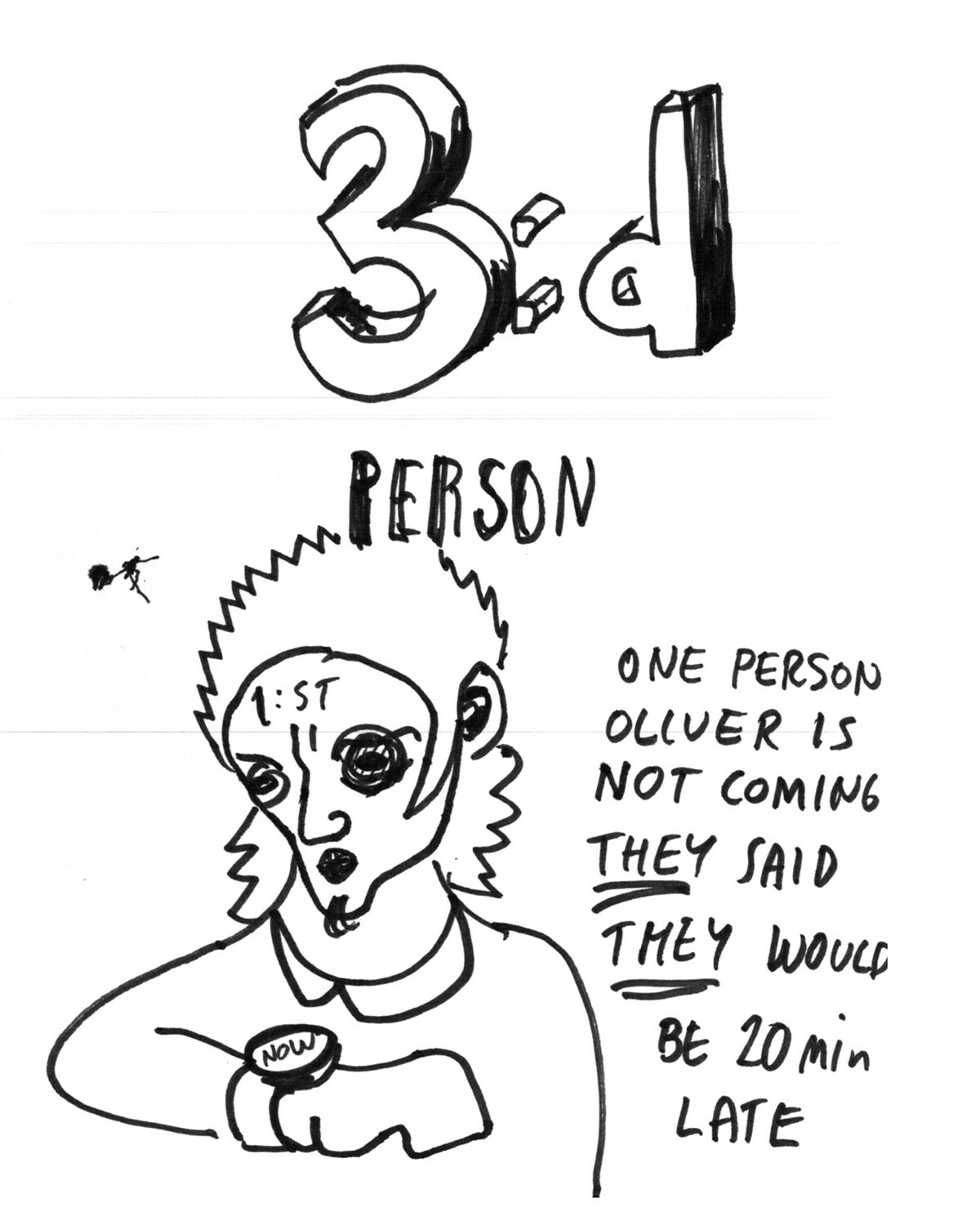

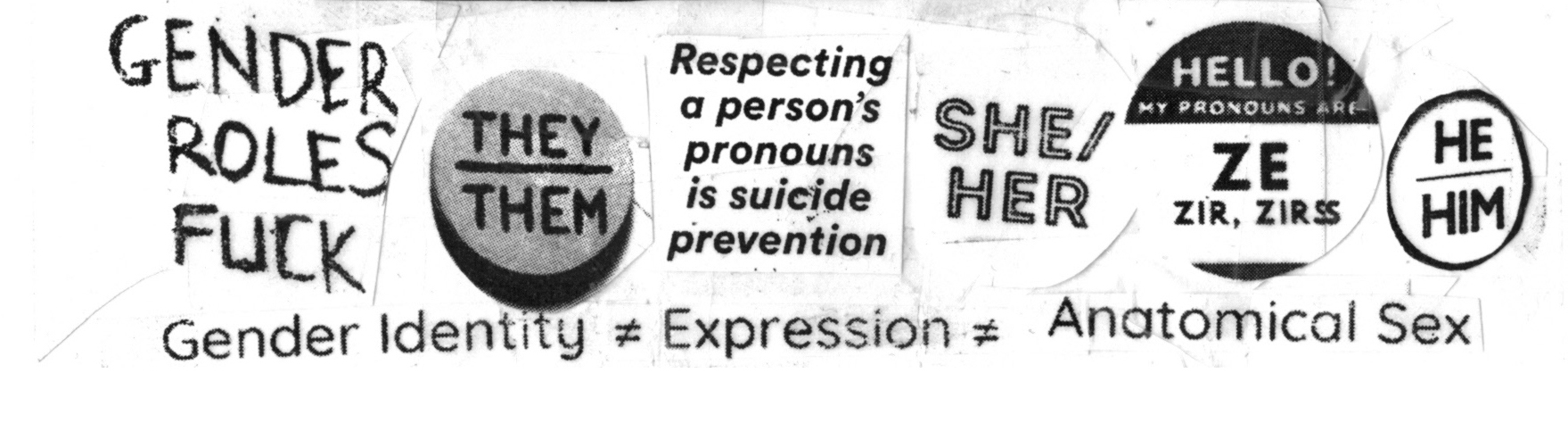

When you are introducing a pronoun go-round explain that pronouns in the third person are words that replace proper names. They are used in order to not repeat the name over and over again. In most languages third-person pronouns are gendered (English: he, she). You can point out that one often assumes a pronoun based on a person’s gender expression. And for some people, their gender identity does not go hand-in-hand with their gender expression. Or they are not comfortable with being referred to by any of the standard gendered pronouns (“he”, “she”) and prefer to go by “neo-pronouns”. In English these include, for example, “they” (used for a single person), “ze” or “xe”. In Swedish the gender-neutral pronouns are ‘’hen’’ and ‘’den’’. In French there is “iel”, “iels” or “ielle”. Remember to respect these choices. You can also explain that even if someone cannot understand the importance of pronouns it is critical to respect that they can be important to others.

Dean Spade (2018, 7) provides helpful instructions on how to introduce a pronoun go-round:

“So when we go around, each person is invited to share their name and information about what pronoun they go by. Some people may use “he/him/his,” “she/her/hers,” some may prefer to be referred to just by their names and not have a pronoun used, some people use “they/them/theirs” as a gender-neutral pronoun, and some people use gender-neutral pronouns that may be new to some people in this room, such as “ze/hir/hirs” or others, and some people are open to being called by more than one set of pronouns. Please listen closely to each other and remember that if you forget what someone said later, you can ask them to remind you before you refer to them. It’s better to ask than to refer to someone by something they don’t like to go by. This exercise is important to helping everyone in this room participate and avoiding unintentionally disrespecting each other, so please take it serious and listen carefully.”

It is good to prepare an introduction before doing a pronoun round since there’s a risk that the situation becomes unsafe. Reb mentioned that it could easily turn into a bad experience when cis people try to show their support by arranging a pronoun go-round but don’t have enough knowledge to arrange it in a good way.

Therefore, both pronoun and access need go-rounds should form part of a larger inclusive engagement. The organisers could, Reb suggests, circulate a statement before an event, a workshop or a university course saying “these are the things we find important”, and “we do pronoun go-rounds as part of this.”

Then, there are the short video and audio clips on this website that could be played as part of an introduction to a go-round.

This is all to avoid confusion about the purpose of the pronoun go-round. “Confusion sometimes creates moments where transphobia and gender privilege are reproduced,” says Dean Spade (2018), stressing that if we were able to decrease confusion we might enable people to be their best self. Starting from a belief that mostly people want to do good and want the best for their fellow humans and the people they meet, one could argue that one of the mechanisms that hinder our ability to do good is the urge to avoid feelings of shame. When a person is not able understand they might feel ashamed. And then, instead of trying to understand the other person, they might attack the source of their shame.

Based on this logic it might be more effective to help people understand before demanding that they take part in activities (such as the pronoun go-round) or to use words that are new to them (such as neo-pronouns, “ze”, “xe” or the Swedish “hen”), if those demands are outside their comfort zone.

Understanding takes time and it is important not to rush things. Together with the group you can try things out, reflect on how they worked, adapt and try again. Experiments can fail, and that is OK. Don’t be afraid of making mistakes. We all make mistakes, what matters is how we deal with them (see “after-care”). If you happen to hurt someone’s feelings, you can apologise. That too can be a learning experience.

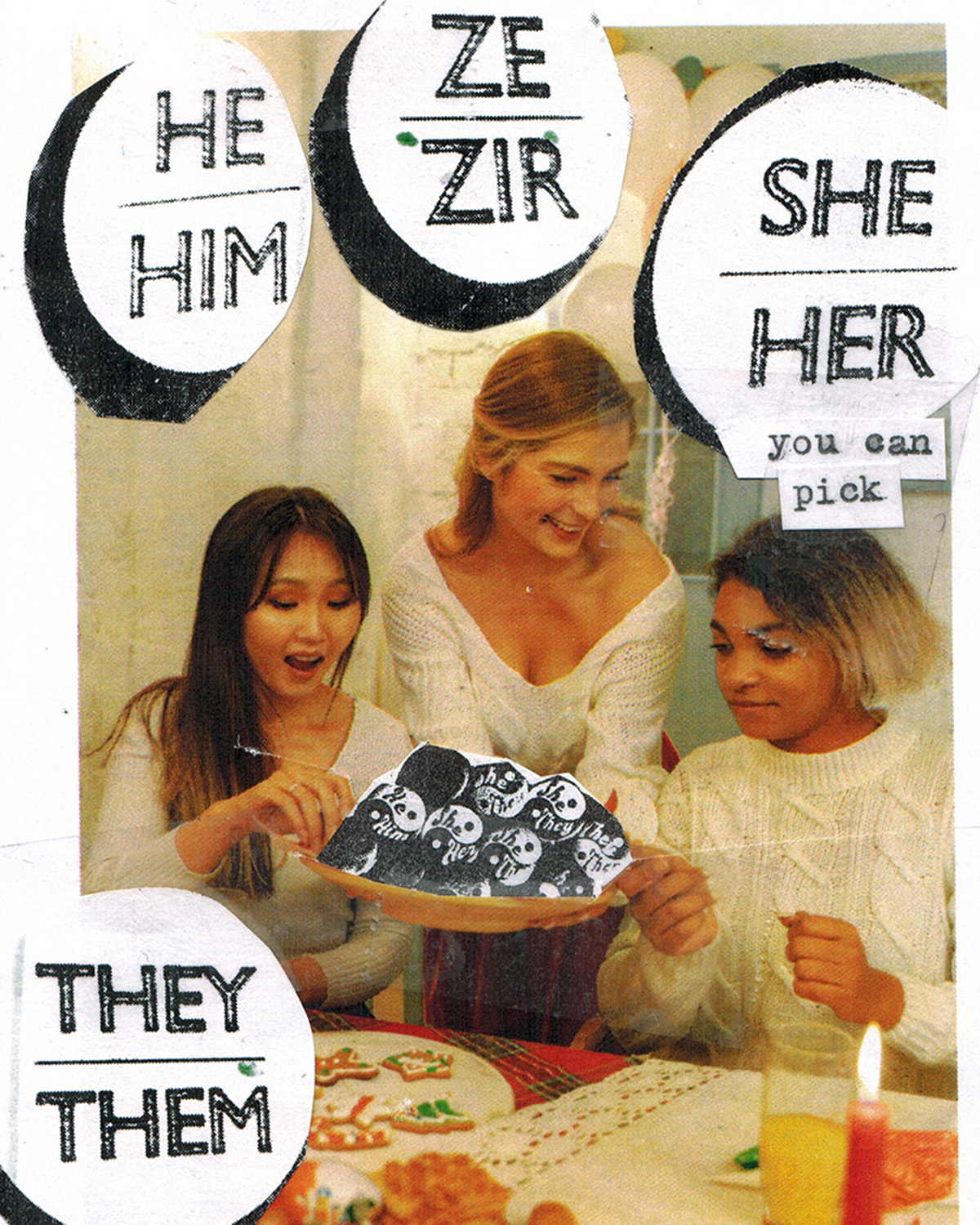

Making signs or tags

is a good alternative to the spoken pronoun go-round. During the workshop in Brussels, we did some paper tags that we could customise by writing our name and pronoun down and sticking them onto us. Wearing these showed how participants wanted to be referred to. This was also good for those who were unable or shy to share this information orally. The tags also kept reminding people who had difficulties hearing or remembering everyone's name and pronoun after the go-round. This was very fun because we took time doing it, around a table. It also helped people who are more crafty than talkative to get into their zone. People started chatting and it broke the ice because it was less formal than a pronoun go-round.

Safe space

“How can we be sure that we are actually creating a safe space when we are asking people to be vulnerable or to come out of the closet?” asked Jean-Paul in her interview.

Pronoun and access go-rounds do not in and of themselves create safe spaces. Although they provide basic elements that can help make a space safer for some — ideally everyone — involved. It is important to recognise the nuances of the concept of safe spaces before digging into what they could mean for the classroom. Safe spaces take on many forms according to the groups they host. They depend on an agreement about what is needed for the participants in order that the participants feel safe. Their function is to create a respectful space where everyone feels comfortable sharing and learning.

Safe spaces are sometimes referred to as emotional or academic. We will not delve into the concept of an academic safe space, however the premise is creating a space for academic dialogue that is potentially uncomfortable and confronting. 17

In the following we want to focus on the concept of emotional safe spaces, which derive from activist environments. Emotional safe spaces were brought into other settings such as festivals and student organisations and then into more institutionalised spaces. But how does a space become emotionally safer? What tools do we have for this?

When we talk about pronoun and access go-rounds as having the potential to create safe(r) emotional spaces we refer to the acts of listening, respecting and enacting. So if someone shares a pronoun choice that contradicts our own understanding of the pronoun in question, it is not appropriate to question or comment on that choice. In this example the space becomes safer by listening to the person sharing their pronoun, respecting their choice of pronoun and enacting the use of that pronoun when we refer to them, both when they are present and when they are not. This goes for access go-rounds as well. When someone says their access needs aren’t being met, it’s important to listen carefully, respect their needs and do what you can to meet their needs, without spotlighting the person.

That said, to claim that a space is safe can be tricky. Because although some might feel emotionally safer from sociocultural micro-aggressions it does not mean others feel the same. We might unintentionally be contributing to feelings of discomfort within the space. Pronoun go-rounds – intended as a tool to make a space safer – can nonetheless foster deep discomfort and unsafe emotional spaces.

So the question seems less “how can we make this space safe”, but rather, “how can we make this a safer space?” How can we listen to the people in the room - really listen - and apply the information shared in order to best be together in the space, in the safest, most respectful way? (See “ethics of care”.)

There is no universal one-size-fits-all approach to safe spaces

Sam described the pronoun go-round as the curating of human experience and social interaction and emphasised the host’s role in deciding what the event is and what we might need to know about each other to make this space the best possible for the specific situation.

Sam

Facilitating a pronoun go-round is not just “ticking a box”. Jean-Paul, for example, reports an experience where, as a trans*womyn self-identified in the initial pronoun go-round as “she” she was then misgendered in the following performance workshop and separated from the women performers’ group.

Jean-Paul

Reb, too, points out that when in a go-round one shares a non-gendered pronoun, and then the people who listened don’t use that pronoun, that it “feels twice as bad. You can’t excuse them because of their ignorance. You know that they know – or at least that you've informed them.”

Sam said in their interview that sometimes they feel the pronoun go-round is being done only for them, among predominantly cis people that are OK with their gender and pronoun assigned at birth (or have never been introduced to the possibility of exploring their identity beyond the socioculturally constructed cis-heteronormative gender binary.)

Sam

The pronoun go-round could be seen as validation and recognition of Sam’s identity, but for Sam the pronoun go-round in mostly heteronormative circles is often alienating.

Sam 21

Reb and Jean Paul, each in different ways, explain in the interviews that their visibility often depends on how safe they feel in a pronoun go-round and how much they trust the people participating in it.

Jean Paul

In the interview Kasra, for example, criticises an instance of an introduction round where participants were asked to introduce themselves by saying which country they come from. Kasra makes clear how alienating it can be to differentiate participants by their nationality or background.

Kasra

A good experience was created for Kasra when a pronoun go-round was done at the end of a workshop, as participants had already gotten to know each other a bit and had developed some trust.

Kasra

When participants are not able to tolerate differences; scapegoating

Building trust in group situations and in classrooms in particular can be difficult when participants do not tolerate differences. Conflicts are important but of course difficult and demanding when scapegoating replaces personal and collective self-criticism. 18

When you witness a student or a group of students being disrespectful to another it’s helpful to bring in an external facilitator who is not familiar with the classroom. One question you can ask yourself and your students at the beginning of the year is “what does safety mean to you?”, and then build from there. Take into consideration that sometimes the classroom is the safest place students have in their lives (or, conversely, the most unsafe) because sometimes students are “out” at school and not at home.

After-care

Sharing your pronoun during a go-round or in any other situation sadly won’t guarantee that people will gender you as you asked to be. Indeed a pronoun go-round is only the beginning of a more respectful classroom. It’s an ongoing effort to create a trans*- and disability-friendly environment. It takes time and won’t happen overnight but we are learning. And if one tries, one also makes mistakes.

MC Coble, Nika Dahlberg-Melin, Eva Weinmayr. Clip: “You can practice”

If we take time to listen and make space to acknowledge potential problems that might come up, then there is plenty of room for improvement. In this chapter we will dig into the “after-care” that can take place after sharing pronouns.

If you have misgendered someone

MC: “If you are the one who is misgendering, first, it’s not about you. Accept and move on. It happens, it’s a process we are all learning. Listen to how the person who has been misgendered is feeling.” 0:21 “practising, taking responsibility for it” MC. (See “safe spaces” for more.)

MC Coble, Nika Dahlberg-Melin, Eva Weinmayr. Clip: “If I, as a teacher, misgender someone”

If you are being misgendered or you witness misgendering

If you do not feel comfortable to address it right away, there are different things to do.

When you don’t have the strength to publicly address it, write an email. If you feel like you have enough energy to send an email to the person who misgendered you or someone else it can have a lot of impact. Most of the time people who receive a letter or email telling them precisely what they have done wrong tend to remember and be a lot more careful in the future.

You don’t have to do this if you feel like you can’t or don’t want to. Sometimes we have enough on our plate. However if you are in a situation of privilege (even in the slightest) and feel like you are confident in addressing misgendering (either because you are a trans*person or because you are an ally) please do. Indeed the more people who address this issue the more benefit there will be to the trans*community, especially to those who are not in a position to address it themselves.

If you’re misgendered in a video conference

During the 2020-2021 COVID-19 pandemic most classes were online. Here it can be tricky to correct people. You could begin an online meeting with doing a pronoun go-round or invite people to put their pronoun next to their username. Not doing a pronoun go-round and rather putting your pronoun beside your name during online meetings can be more comfortable, especially when it is with people you have never met and if online meetings make you anxious. Sometimes, even if people know your pronoun, misgendering might still occur during the online meeting. It can be hard to interrupt people in real life, let alone online.

You can use the chat box as a reminder. There is not necessarily a need to point out who misgendered who or who was misgendered but simply remind participants by writing something like, “Our pronouns are written next to the username. Let’s use them!”

At the beginning of the online meeting you may agree on a letter or symbol that can be entered in the chat when misgendering occurs, so people can see it quickly without interrupting the conversation. In meetings with the camera on you may wear a handmade name and pronoun tag (as you would in a regular meeting) and if misgendering occurs you can just point to it with your fingers.

Start a conversation with the person who has been misgendered

The trans*community is as diverse as any other community and not everyone agrees on how they want to be treated. That’s why it is important to talk to the misgendered person directly. Do not blindly follow guidelines that make you feel comfortable and not the person affected.

If someone outs themselves as a binary and/or non-binary trans*person, it is the group’s responsibility to make the place accessible for them. Find a moment to talk to them directly. Understand what their needs are. Acknowledge that they might not know what they need, that they don’t feel comfortable talking about it yet or don’t want to. Do your research and let them know that once they feel comfortable you are there to listen.

Sometimes outing oneself is exhausting and it is an ongoing practice when living a non-cis-heteronormative identity. If someone has misgendered you, you don’t have to be nice to them about it. As much as diplomacy can help in some situations it is equally important to give space to anger. Bursting out in anger can be a powerful tool for educating in some situations and it is not your duty to protect cis-hetero-fragility.

But then again anger is also an emotion that is often weaponised against those – often from marginalised and minority groups – who speak up about mistreatment and discrimination.

Fluidity

Repeating pronoun go-rounds. Unlearning the binaries. Testing things out

There is a challenging complexity to repeated pronoun go-rounds. We expect others to memorise and to practice our pronoun in order to avoid the pain that results from being misgendered. Here a certain obligation and heaviness comes in. People who want to respect each other’s pronouns don’t want to say the wrong thing, and repeated pronoun go-rounds can also be moments of experimentation.

Undoing the gender binary

Many of our interviewees described an experience of enlightenment when they first understood that pronouns can shift, and they indicated the benefits of having repeated pronoun go-rounds in the same group. MC said, “it really struck me, when I understood that the regular pronoun go-round allowed me to test things out. I could be ‘they’ today or ‘he’ tomorrow”. The pronoun go-round is a way of trying things out as a resistance to the framework of a static binary. Repeating the pronoun go-round regularly with the same people could provide a space for testing out and disrupting the gender binary and for the possibility of presenting oneself as a multiplicity of genders. Regular pronoun go-rounds are important for putting emphasis on the process. Imagine doing a pronoun go-round at the beginning of every class. Maybe students who were first scared or unsure of how to talk about their gender identity will start to see the pronoun go-round as a way to experiment and figure out what feels best.

This is my experience of the pronoun go-round. During the first TTTT workshop I felt like I was “forced” to come out, only to realise I just needed that moment to accept that I wanted to be referred to as “they/them”, and then a few weeks later as “he”.

Resisting categorisation

The process-oriented aspect of pronoun go-rounds can go one step further. By constantly shifting a pronoun and its implicit identity category, the go-round could help to dismantle a logic of fixed identity categories. Kate Drabinski, a scholar in transgender studies in the US, observes: “Is our subject matter women and men, gays and lesbians, transgender people? Or is it rather the production of those categories and how they come to matter?” Identity categories have been constructed and, as Drabinski says, “identities are historical artifacts rather than static realities” (Drabinski 2014, 140). She underlines the importance of understanding how these categories operate and acknowledging the struggles they invoke for those who live on their margins. Many transgender studies scholars stress that transgender does not signify a static identity category but a multiplicity of practices. Susan Stryker proposes, for example, to think of transgender phenomena as practices and acts rather than identities (Stryker and Aizura 2013, 7). For her, transgender phenomena are any practices or acts that step outside the boundaries of gender normativity. 19

Stryker and Drabinski’s suggestion that transgender phenomena extend far beyond questions of identity stresses that, rather than cementing identity categories the pronoun go-round opens them up, creating new constellations and configurations.

Insisting on absence: I am not something

“It’s taken a lot of resistance that I want to leave my gender and my sex life uninscribed – that it took me years to consider the fact that I did not have to name my gender or sexuality at all, so that now I must always tell people that I am not something. I insist on this absence more, even, than I used to insist on my identities.” (Fleischmann 2019, 64)

The naming of identity categories has its complexities, problems and benefits. On the one hand, we critically challenge normative sociocultural categorisation. On the other, we recognise the importance of self-categorisation, precisely because it claims recognition for marginalised identities that do not always want to be understood as external or in relation to the cis-hetero norm.

Through affiliating ourselves with an identity category we can develop a sense of belonging, become part of communities and better escape the loneliness of non-normative life. It can help to develop an understanding of our identities in a more nuanced and complex way than the cis-normative patriarchal society gives space for.

Gender binarism can help the visibility, for example, of butch/fem or butch/butch relationships. Those types of relationships play with aspects of the gender binary. However, they are not replaying the heteronormative cis-binary system, as some might think. As Leslie Feinberg shows in Stone Butch Blues (1993) being a lesbian butch was sometimes the only category available to people who were trans* and did not have access to or knowledge of transgender people.

Experimenting with sexuality within a rigid binary can allow people to experience different gender expressions and/or identities, and sometimes helps them to come out as trans*. That was my personal experience and C. J. Hale (1997, 223) also talks about it in “Leatherdyke Boys and Their Daddies: How to Have Sex without Women or Men”. It’s important to remember that sometimes identifying with a category is all you have to survive in a violent world. Indeed, in medical settings in France you often have to play a role to get what you need, if you want surgery and/or hormones, for example.

The point is not full opposition to normative gender and sexuality categories, but rather critical reflection on them, and the re-evaluation of the strict codes of conduct that are enforced. It is about opening the categories up to criticism, to expand and broaden the ways in which we access our identity development and to reimagine the status quo not as binary but as a spectrum or constellation. This includes multiple identities, identities that are not fixed but rather in an ongoing process, identities that are not framed by a simple and restrictive gendered coding.

The prefix trans- (“across”, “beyond”, “through”) indicates a movement, an in betweenness that does not belong to one category or another. As an umbrella term, trans* makes room for countless identities that find themselves identifying with the binary or being on the gender spectrum. These identities are often informed by years of self-reflection and introspection. They break free from the rigid and internalised cis-normative categorisation and exist as fluid and adjustable. They are in constant processes of invention or experimentation with new descriptors, which rethink, reimagine and rename gender non-conforming experiences.

When I am asked in a pronoun go-round to name my identity, for example, formed by gender, race, nationality, etc., it is often assumed that these are stable, or at least temporarily stabilised identity categories ... to me there is a huge problem with being categorised from the very start. As Marquis Bey says: “In being uninscribed, one gives oneself over to movement. It is a refusal to name oneself because one knows that the name will ultimately be inadequate, it coming from the language available, a language from without and dictatorial of how we can exist. This language, we know, cannot be escaped entirely, but we refuse it anyway …” (Bey, 2020, chapter Uninscription).

Still, the pronoun go-round does not necessarily break with the classificatory logic. Even if we are able to move back and forth between the different available gender signifiers it is still an exercise that buys into the logic of categorisation and naming. Thus, naming can be limiting and liberating at the same time. Liberating, when the pronoun go-rounds are done repeatedly over a period of time because one can experiment with different pronouns and therefore make space for fluidity; make space for practice in the sense of experimenting, trying, testing, reflecting, adjusting and by that pushing the archaic logic of assumed fixed identities, and of course the binary logic of female and male. Dean Spade (2018) summarises the complexities and anxieties related to naming and categorisation in the following way:

“I know many people can relate to fearing the moment when the pronoun go-round gets to you, and feeling like a set of assumptions are made based on the answer to that simple question. To me, the problem is not the pronoun go-round, it’s the gender system, and binaristic thinking of all kinds. In an ideal world, after having heard you state your name and pronoun in the go-round, people would assume nothing other than that is what you want to go by. It would not mean they know what kind of identity, body, behaviour, or politics you have. [...] People may assume someone is or is not trans because of the pronoun they use, or that they are or are not queer, radical, feminist, relevant, interesting, etc. I think this judgment flows in many directions. I have feared others would think I was too “square” for using he/him pronouns. Other people I know have feared others would erase their transness because they used the same pronoun that was assigned to them at birth. Some friends who are trans and using a pronoun different than what they were assigned, but who are perceived as non-trans, also feel unseen in these moments.”

As already quoted in the beginning of this piece, Dean Spade concludes:

“The thing about the pronoun go-round is that it is not meant to and cannot take care of all the many complex problems of judgment, identity and anxiety that exist around our complex lives and our political movements. It is merely an attempt to create a practice of not assuming we know what someone goes by just by looking at them.” (Spade 2018)

“Pass” option

Celebrating the choice to say “pass” is an act of inclusivity and empathy. Being able to choose what one wants to share and what one doesn’t is important because not everyone is comfortable with sharing their pronoun. The option to “pass” is a mechanism enabling someone who might feel distressed by sharing their pronoun to still take part in the go-round. You can pass your turn by saying the word “pass”, by making a gesture of crossing your arms over your chest or using other signs or words that have been agreed upon.

MC Coble, Nika Dahlberg-Melin, Eva Weinmayr. Clip: “What is ‘pass’ in a pronoun go-round?”

The pass should be used freely but also mindfully. “Pass” is tricky because of the politics of the pass when it comes to micro-aggressions or violence. For example, it can be problematic if a cis person who has never had any problems or thoughts about their pronoun assigned at birth passes on saying their pronoun during the go-round. It can potentially invalidate the importance of the correct pronoun of somebody else in the room. It also puts other participants in a situation of having to assume, or having to ask later. If you don’t want to be assumed about, having to assume about someone else is usually something you don’t want to do.

Words matter

Descriptors are not neutral

Not having a pronoun preference is absolutely fine but can become problematic when cisgender people say “I don’t care what pronoun you use for me”. This statement can invalidate a trans* person’s need for particular pronouns (Anderson 2016). MC describes how this – often unintentional, but nonetheless ignorant – way of wording makes them feel like their pronoun needs are silly or won’t be taken seriously.

MC Coble, Nika Dahlberg-Melin, Eva Weinmayr. Clip: “Different reactions to a pronoun go-round”

West Anderson suggests saying, “all pronouns are fine", rather than “I don’t care what pronouns you use”, because it allows cisgender and questioning people to experiment with pronouns without unintentionally communicating that pronoun choice is not important (Anderson 2016).

Unintentional bias

Similar unintentional bias can be heard in access go-rounds. In these go-rounds, common in activist spaces, people can share what their access needs are (see “Access go-round” above). Dean Spade brings the example that people who have not been exposed to a disability justice framework sometimes say “I do not have access needs” when it is their turn, rather than “my access needs are being met”. This small difference in wording has major implications. The first (“I do not have access needs”) confirms an ableist idea that some people’s needs are “neutral” or “normal” or that there are no access needs at all. This wording forgets, as Spade points out, that “the way spaces and activities are constructed has some people’s needs in mind while others’ are erased and excluded” (Spade 2018, 3). Instead, when you say “my access needs are being met” you acknowledge that everybody has access needs, but some needs are met and others are not.

Beyond the straightforward suggestions mentioned above lies the use of language, terminology and descriptors. Words, the ways they are used and by whom is often based on conventions and habits that affirm binary language structures. And so, as we move towards more inclusive and intersectional environments, the way we use language must follow. We have to be careful that we are not indirectly misgendering someone by referring to them through a gendered lens. As an example, if a non-binary person or a trans man becomes pregnant we can refer to them as a “pregnant person” rather than using the gendered, binaristic equivalent.

This is an ongoing practice of unlearning, of constant revisiting and rethinking how we use language. It requires understanding where and why violence in language occurs and at whose cost. We can start by detaching our learned gendered linguistic conventions from biological understanding, clothing, expression or professions. But most importantly we must actively reset our way of thinking through language, of reading coded elements in our lives through a gendered lens.

How to become an ally

Did you know that people who are transgender or gender non-conforming can be fired from their jobs under state law in more than half of the states in the US simply for being transgender – and that it is perfectly legal because there’s no federal law that explicitly bans this kind of discrimination? (Straight for Equality 2020, 49)

You can become an ally. Outspoken allyship is crucial to support vulnerable trans* persons in their struggles and to prevent self-harm.20 Particularly in educational settings, a broad spectrum of diverse allies are needed – and that also includes people who are not members of the LGBTQI+ community.

During our first TTTT workshop in Brussels, one participant told me that, as a cis-person, she felt it was very important to name herself “she”. With this, she hoped to counter the widespread assumption that there is no need to state a cis person’s pronoun because it is seen as the norm. I see this as an example of active allyship.

The Straight for Equality Workbook has come up with great tips what allyship implies:

- Allies want to learn. Allies are people who don’t necessarily know all that can be known on LGBTQI+ issues or about people who are LGBTQI+, but want to learn more.

- Allies address their barriers. Allies are people who might have to grapple with some barriers to being openly and actively supportive of people who are LGBTQI+, and they’re willing to take on the challenge.

- Allies are people who know that “support” comes in many forms. It can mean something super-public [...] It can also mean expressing support in more personal ways through the language we use, conversations we choose to have and signals that we send. And true allies know that all aspects of ally expression are important, effective and should be valued equally.

- Allies are diverse. Allies are people who know that there’s no one way to be an ally, and that everyone gets to adopt the term in a different way …and that’s OK.

Besides cis-hetero allyship it is also important to advocate for intersectional allyship, because one can observe discrimination and micro-aggressions within and between LQBTQI+ communities as well.

See also Davey Shlasko’s Trans*Ally workbook as a further learning resource.

In your school

The following tips are for all trans*people, trans*allies and people who want to become a trans*ally. Therefore this section addresses students, teachers, administrators and school managers.

As a trans*person, it’s sometimes hard to be on your own and reaching out to other trans*people can help a lot. If you know other “out” trans*persons in your school you can create a group with them about the issues faced. Sometimes creating an entity helps build strength in a transphobic institution – much like a workers’ union. You can make flyers and posters to create awareness around trans*issues. You can also create a programme for your school to improve the curricula and classroom for trans*students. Gathering in a group can make you less vulnerable and more visible.

You can ask your tutors and managers for a staff training by trans*feminist associations so the teachers are more aware and don’t feel confused or helpless.

That’s something that we tried at my art school in France. We contacted a French association called Outrans (FR) to see how they could give a training/workshop to everyone at the school who wanted it. There are also ways to get funding for this kind of work, for example, from the student union or from the university, which give funding to “students action”.

If the administration isn’t making it easy and you need to find allies, if you feel comfortable enough you can circulate the booklet Mon proche est trans, comment l’aider au mieux? to potential allies .

Also remember that now in France you are legally entitled to request that your university use your chosen name. If no one is listening to you you can print out the official state declaration by the French Ministry of Education “Recommendations de favoriser l’inclusion des personnes transgenre dans la vie étudiante et dans les établissements d’enseignement supérieurs et de recherche”, 2019.. Give it to those who make it hard for you to change your name.

Furthermore, there is this great booklet in French Prénoms d’usage à l’université made by the student union Solidaires Etudiant*e*s in 2017 on how to change your name in your school. Why not use the printers at your school to print and circulate them?

In case you feel lost there is this great map Carte des associations trans en France. listing all the French trans*associations, in case you need extra help. For Belgium there is Tous.tes bien informé.es by Genre.s Pluriel.le.s, which talks about the laws concerning schools respecting trans*students.

Swedish resources include the manual Oavsett kön written by RFSL (Riksförbundet för homosexuellas, bisexuellas, transpersoners och queeras rättigheter) for working with equality and trans issues. And Skolverket, the Swedish National Agency for Education, published the book Tyst i klassen in 2006, including tools to deal with heteronormativity and homophobia when working with school children. Swedish trans*association Transformering has several informative articles about trans* issues such as pronouns (Pronomen) and trans* issues relating to school contexts (I skolan.).

Transammans’ Åsiktsprogram, 2020. is a good source of information in Swedish and on the Swedish teachers’ association’s web platform you can find Tips från transpersoner (English: “some hints from trans*persons”) published by Sara Lövestam in 2013.

We mostly focused on gathering resources for Swedish- and French-speaking communities to complement the many sources already circulating widely in English.

These resources are helpful for students, teachers and administrators alike. It is for all that want and need to learn more about trans*issues at school, whether as a trans*person, an ally or somebody wanting to become an ally.

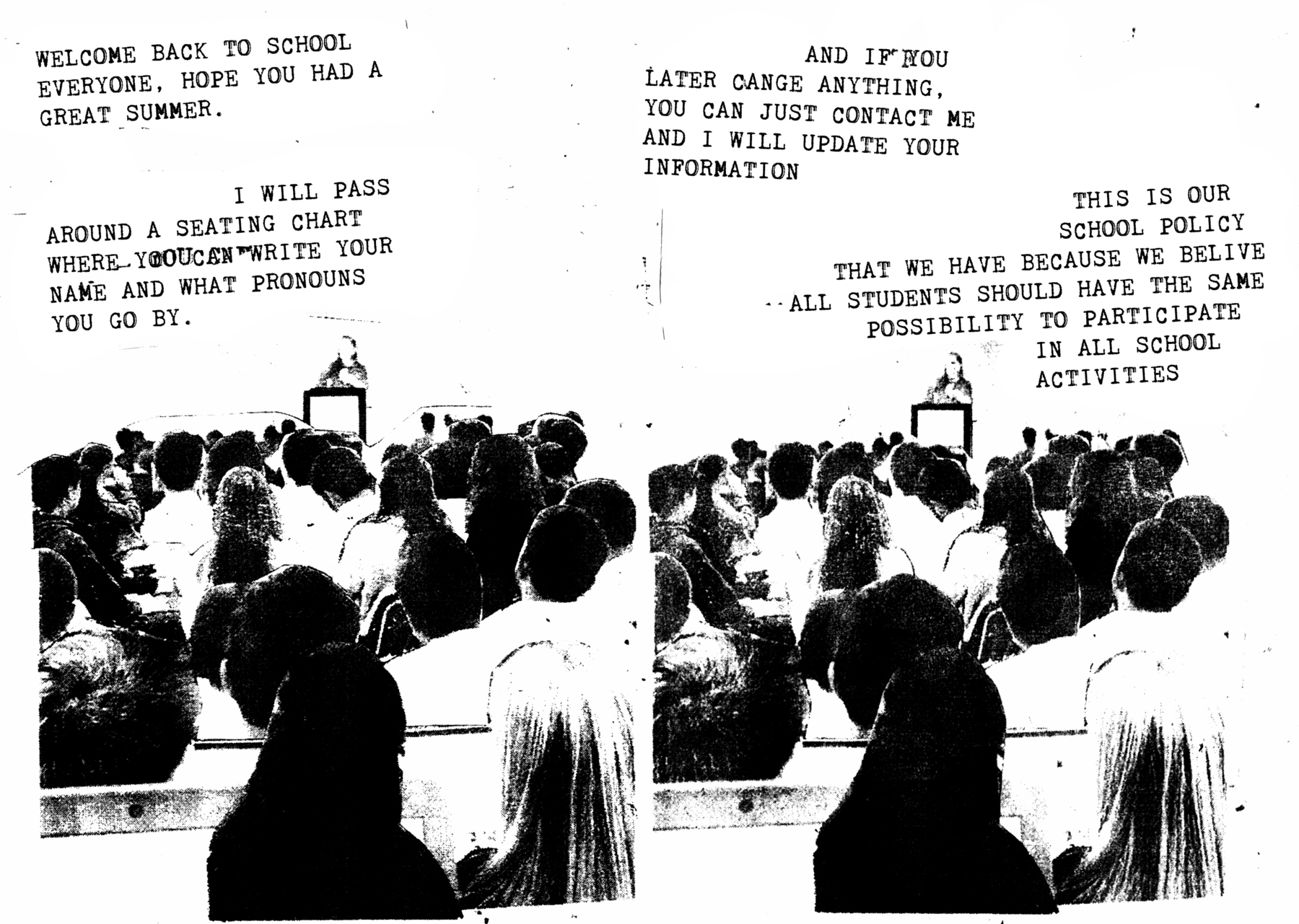

We are only at the beginning of understanding the importance of these resources. MC, for example, points out that they, as a teacher, only recently started doing pronoun go-rounds in class and are surprised they didn’t do it sooner: “I did not understand the importance of it and had no experience of people facilitating it.”

Outing oneself as a teacher, as a person in a position of (some) power, can also help others in the room feel less alone and a bit safer.

I am thinking of my friend who is a teacher and who comes out at the beginning of every school year: “I am the teacher and my pronouns are they/them, you can tell me what your pronoun is.” Being visible and outspoken can sometimes dramatically change the setting.

Never feel bad for asking for a pronoun go-round.

I feel like we should always be asking too much. I also realised that nothing will change if someone isn’t asking too much. Being a demanding person is how you can change an institution. They also see you as a possible threat, so they take you more seriously (think about the history of unionised workers). If you demonstrate that what you are asking is a basic need they can’t really say much. I feel like if you show up with a big folder and a lot of stuff to say they can only say “OK”. Don’t be afraid to be annoying and to complain. 16.

How we wrote this text

We owe this text to many people. It began with the preparations for a pronoun go-round during the first TTTT workshop in Brussels, when Eva asked MC Coble (US, SE) and Nika Dahlberg-Melin (SE), both living in Gothenburg, for guidance and a conversation. Short video clips from this recording were used to introduce the pronoun go-round to the participants meeting in Brussels (from art schools in Belgium, France and Sweden). A big thank you goes to MC Coble for their generosity in sharing research and resources that were so helpful in kicking off the working group, and to Åke Sjöberg, Eva Weinmayr, Flo*Souad Benaddi, Kolbrún Inga Söring, who wrote this piece together.

Back from Brussels, Inga recorded interviews with Tori and Håkan (SE), Sam (UK, SE), Kasra (SE). Jean Paul (US) and Åke recorded a conversation with Reb (SE). These conversations, along with many other informal chats and exchanges, helped to get a grasp of the complexities connected to pronoun and access go-rounds in educational settings. In this text we draw heavily on the amazing work of activists and organisations that shared practical experiences in the form of guides, workbooks and manuals, which made us think and educated us. These resources are listed in the library, and under “organisations”.

This text has been written collectively via a shared online writing pad. In weekly meetings over five months we read aloud together and discussed each other’s ideas, thoughts and additions to the text. It has become a piece with multiple voices and that’s good because it shows the diversity of the working group in terms of gender, age and cultural background. To share our different experiences was very valuable and certainly added to the complexity of this multivocal text. We learned a lot from each other and that’s how we approach teaching by thinking together.

Teaching Materials

The pronoun go-round (video)

Click here to watch entire conversation between MC Coble, Nika Dahlberg-Melin and Eva Weinmayr (January 2020), 53:55 min

Click here to watch entire conversation between MC Coble, Nika Dahlberg-Melin and Eva Weinmayr (January 2020), 53:55 min

Pronoun go-round (guide, hand-out, zine)

You can download this guide as PDF and print it out as an A5 zine. We have it in English, French and Swedish.

References & Resources

- Ahmed, Sara. Complaints!. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2021.

- Anderson, West. “Pronoun Round Etiquette: How to create spaces that are more inclusive”. The Body is not an Apology. October 22, 2016.

- Bey, Marquis. “The Problem of the Negro as a Problem for Gender”. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, manifold.umn.edu, 2020.

- Blanco, Mykki. “Mykki Blanco speaks about race in whiteface”. Dazed, August 23, 2018. Watch video

- Drabinski, Kate. “Identity Matters: Teaching Transgender in the Women’s Studies Classroom”. Radical Teacher No. 100 (Fall 2014). DOI 10.5195/rt.2014.170.

- Feinberg, Leslie. Stone Butch Blues, Ann Harbour Michigan: Firebrand Books, 1993

- Fleischman T. Time Is the Thing a Body Moves Through. Minneapolis, Mn: Coffee House Press, 2019.

- Fogarty, Mignon. “Themself or Themselves”.Quick and Dirty Tips, June 8, 2017.

- Hale, C. “Leatherdyke Boys and Their Daddies: How to Have Sex without Women or Men.” Social Text, January 23, 1997.

- Hedva Johanna. “Hedva’s Disability Access Rider”, Sick Women Theory, August 22, 2019.

- Held, Virginia. “The Ethics of Care: Personal, Political, and Global” Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2006, 21.

- Ho, Katherine. “Tackling the term: What is a safe space”. Harvard Political Review, January 30, 2017.

- Evaluation des Conditions de prise en charge médicale et sociale des personnes trans e de transsexualisme. A report commissioned by the French Government evaluating the medical care for the trans*community in France. Inspection générale des affaires sociales-RM2011-197P, 2011.

- Joy, Melanie. Powerarchy: Understanding the Psychology of Oppression for Social Transformation. Oakland: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2013.

- Laugier, Sandra. ”L'éthique comme politique de l’ordinaire”, in Politique du care, Multitudes, 2009/2-3 (n° 37-38): 80–88.

- Manion, Jen. “The Performance of Transgender Inclusion: The pronoun go-round and the new gender binary”. publicseminar.org, November 27, 2018.

- Mingus, Mia. “Access Intimacy: The Missing Link”, Leaving Evidence, May 5, 2011.

- Rich Adrienne, Blood, Bread, and Poetry: Selected Prose, 1979-1985. New York and London: Norton, 1986.

- Schlauderaff, Sav and Zia Puig. “15 Tips to create a radically accessible space”, The Queer Future Collective. No date.

- Schulman, Sarah. “Conflict is Not Abuse Overstating Harm, Community Responsibility and the Duty of Repair”, Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2017.

- Spade, Dean. “We still need pronoun go-rounds”, deanspade.net, December 1, 2018.

- Spade, Dean. “Some Very Basic Tips for Making Higher Education More Accessible to Trans Students and Rethinking How We Talk about Gendered Bodies”, in The Radical Teacher, No 92, 57–62.

- Spence Messih and Archie Barry. “Clear Expectations, Guidelines for institutions, diverse artists, galleries and curators working with trans, non-binary and gender diverse artists”, 2019

- Stryker, Susan and Aren Z. Aizura (eds.), Transgender Studies Reader 2, New York and London: Routledge, 2013.

- Tronto, Joan C., “Who Cares? How to Reshape a Democratic Politics”. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015.

- Zeluf, Galit, and Cecilia Dhejne, Carolina Orre, Louise Nilunger Mannheimer, Charlotte Deogan, Jonas Höijer, and Anna Ekéus Thorson. “Health, disability and quality of life among trans people in Sweden–a web-based survey”. BMC Public Health, 2016.

- Walby, Sylvia quoted in Giddens, Anthony and Simon Griffiths. Sociology (5th ed.). Cambridge: Polity, 2006, 473–4.

Guides & Workbooks

English

- Trans*Ally Workbook – Getting Pronouns Right & What It Teaches Us About Gender. Davey Shlasko, 2014.

- The guide to being a trans ally. Straight for Equality, 2020.

- Supporting LGBTQ+ Youth of Color. GLSEN, webinar

- Educator, Policy and Advocacy Resources, GLSEN.

- “Functional and Access Needs Support A toolkit for empowering inclusive action”, The American Red Cross Greater Chicago Region, 2014/19.

French

- Recommendations de favoriser l’inclusion des personnes transgenre dans la vie étudiante et dans les établissements d’enseignement supérieurs et de recherche. French Ministry of Education, 2019.

- Trans*Guide – Guide d'accompagnement pour l'inclusion des personnes trans dans l'enseignement supérieur en fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles, 2018, published by Direction de l’Egalité des chances du Ministère de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles, en collaboration avec l’Académie de Recherche et d’Enseignement Supérieur (ARES).

- La transidentité, la transphobie, Les guides de Chrysalide: N°1, 2009

- Les transidentités et les proches, Les guides de Chrysalide: N°2, 2010

- Nos brochures, Les guides de Chrysalide. Archive of Chrysalide brochures and documents

- Prénoms d’usage à l’université. Solidaires Etudiante-e-s, 2017.

- Carte des associations trans en France, Wikitrans, mapping trans*associations in France.

- Tous.tes bien informé.es. Genre.s Pluriel.le.s, Brussels, 2019.

Swedish

- Oavsett kön – Handbok för arbete med jämställdhet och trans. RFSL, 2020.

- Transformering, Ordlista. and RFSL's glossary Begrepsordlista, March 17, 2021.

- Tyst i klassen. Skolverket, National Agency for Education, Sweden, 2006.

- Tips från transpersoner by Sara Lövestam. Lärarnas Riksförbund, 2013.

- Åsiktsprogram, Transammans, 2020.

- I skolan, Transformering.

- Pronomen, Transformering.

Organisations

Links to organisations who support, advocate, educate and provide resources:

- Straight for Equality (US)

- PFLAG trans* family resources (US)

- GLSEN (US)

- Gender Spectrum (US)

- Sylvia Rivera Law Project (US)

- TGEU (EU)

- Trans-inter-action (FR)

- Outrans, Association féministe d’autosupport trans. (FR)

- Wikitrans (FR)

- Transposées (FR)

- Genre.s Pluriel.le.s (BE)

- Transformering (SE)

- RFSL, Riksförbundet för homosexuellas, bisexuellas, transpersoners, queeras och intersexpersoners rättigheter (SE)

-

We chose to use spelling conventions when writing this text. We use “trans*” instead of “trans”. Following many people's practice we use the asterisk to symbolise the unknown, the future and ongoing change, because being trans* is not a fixed identity. ↩

-

You can download the whole PDF booklet Guide to being a trans ally, which contains the glossary, published by Straight for Equality in 2020. ↩

-

“Cis-hetero” is a composite of “cis”, which refers to an individual whose gender-identity aligns with the one typically associated with the sex assigned to them at birth, and “hetero(sexual)”, which refers to a person who is emotionally, romantically and/or physically attracted to a person of the opposite sex/gender. ↩

-

“Patriarchy” refers to a system, society or government controlled by men. It is a social system in which men hold primary power and predominate in roles of political leadership, moral authority, social privilege and control of property. Patriarchy has been described “as a system of social structures and practices in which men dominate, oppress and exploit women”. (Walby 1990, 20) ↩

-

According to the National Museum of African American History, whiteness and white racialised identity refer to the ways that white people, their customs, culture and beliefs operate as the standard by which all other groups are compared. Whiteness and the normalisation of white racial identity throughout Europe, as well as its colonial history, have created a culture where non-white people are seen as inferior or abnormal. This produces structures based on white privilege and systemic racism. ↩

-

Ableism is the discrimination of and social prejudice towards people with disabilities. It is based on the belief that people with typical abilities are superior. Ableism is based on the assumption that disabled people require “fixing”, in turn defining people by their disability. Similar to racism and sexism, ableism classifies entire groups of people as “lesser” and propagates harmful stereotypes, misconceptions and generalisations of people with disabilities. Because the world we live in was not built with people with disabilities in mind it is often inherently ableist. Abled, enabled or non-disabled privilege refers to these unearned benefits. This privilege is rooted in two cultural beliefs. First, that a “normal” person is one who can see, walk, hear, talk, etc., and who has no significant physical, cognitive, emotional, developmental or intellectual divergence. And second, that disability is abnormal and therefore a (social) disadvantage. These beliefs or societal models mean that many cultures have set up social expectations, structures, cultural mores and institutions to accommodate non-disabled and/or enabled people by default and which dismiss and/or marginalise the needs and experiences of disabled and/or differently-abled people. ↩

-

Classism is a belief that a person’s social or economic station in society determines their value in that society. Classist behaviour reflects this belief in the form of prejudice or discrimination based on class. Social class refers to the grouping of individuals into a hierarchy based on wealth, income, education, occupation and social network. The term “classism” can refer to personal prejudice against lower classes as well as to institutional classism, just as the term “racism” can refer either strictly to personal prejudice or to institutional racism. ↩

-

See Dean Spade’s article “We still need pronoun go-rounds” in which he responds to Jen Manion’s text “The Performance of Transgender Inclusion: The pronoun go-round and the new gender binary”. Manion claims that pronoun go-rounds might produce more harm than good. Spade, however, argues that despite their complexities, pronoun and access go-rounds are a helpful tool for “creating a practice of not assuming”. ↩

-

The support of some people who weren’t interviewed but provided ongoing advice was extremely valuable during this process. We tried our best to credit everyone who in some way or another supported this project. ↩

-

Excerpt from recorded conversation between MC Coble, Nika Dahlberg-Melin and Eva Weinmayr, January 2020, HDK-Valand, Gothenburg. ↩

-

The act of preparing a meal, for example, can be considered caregiving if the receiver needs help (such a small child), but not considered caregiving if the receiver could have done it themselves (such as an adult male). ↩

-

Emotional labour’s low ranking in most institutional value systems today might be explained by its historical link to reproductive labour – mostly carried out by women – in the domestic sphere. Productive labour, often seen as “real” labour, has historically been carried out by men in the public realm. This dominating preference for the value of productive labour seems still very much to dictate our workplaces today, including the university. ↩

-

Often, as French philosopher Sandra Laugier (2009) claims, care work is an “ordinary reality: the fact that people look after others, care about them and thus keep the world running”. In France, professional needs-based caregiving (such as personal aid, nurse, nanny, etc.) is an underpaid job often carried out by cis women who have immigrated, and who are often people of colour from the Maghreb. Inequalities perpetuate a colonial and patriarchal ideology. (“Le care renvoie à une réalité ordinaire : le fait que des gens s’occupent d’autres, s’en soucient et ainsi veillent au fonctionnement courant du monde.” Translation by Deepl.com) ↩

-

We suggest looking into more resources about access points: “15 Tips to create a radically accessible space” by Sav Schlauderaff & Zia Puig from The Queer Future Collective. This handout provides guidelines on how to plan an event that is accessible for as many people as possible. See also the booklet “Functional and Access Needs Support” by The American Red Cross Greater Chicago Region focuses on an important range of inclusive actions to welcome and care for people with different access needs. ↩

-

Equality (in French: égalité) or social equality refers to the idea that all people in society have equal rights. The concept of “equality” differs from the concept of “equity” (in French: équité), which places more focus on whether something is fair, for example, a process that leads to an equal or fair outcome. “Equity” refers to the just and fair provision of resources to all individuals, which does not necessarily mean these provisions are equal, because there might be differing needs in order to arrive at a fair or “equal” outcome.

↩

↩ -

See Sara Ahmed’s blogpost “Complaint and Survival”, 2020. Ahmed’s upcoming book Complaints published by Duke University Press in 2021 will also challenge those issues: “In June 2017 I began working on a project on complaint, which was inspired by my own experience of supporting students through multiple enquiries into sexual harassment and sexual misconduct. Another way of saying this: my project was inspired by students. The project involves gathering written and oral testimonies from those who have made complaints about experiences of abuse, harassment and bullying within universities as well as those who decided not to make complaints despite their experiences of abuse, harassment and bullying. The university here provides a research field; one with which I am familiar. I am concerned with what it means to identify and challenge abuses of power. I have a simple premise: the experience of identifying and challenging abuses of power teaches us about power. The project is thus concerned with the experiences that lead to a decision about complaint as well as the experiences of complaint. By complaint I am not just referring to formal complaints but to a range of informal as well as formal means by which challenges are expressed.“ https://www.saranahmed.com/complaint ↩

-

The idea of an academic safe space stresses the importance of taking intellectual risks and explore lines of thought that might make others uncomfortable. Here, “safety” refers to the protection of freedom of speech. This type of safe space is commonly practiced in “classrooms and discussion groups, where open dialogue is particularly valuable” (Ho 2017). ↩

-

In her 2017 book, "Conflict is Not Abuse Overstating Harm, Community Responsibility and the Duty of Repair", Sarah Schulman explores our contemporary culture of scapegoating. Illuminating the difference between conflict and abuse Schulman reveals how punishment replaces personal and collective self-criticism, and shows why difference is so often used to justify cruelty and shunning. In the publisher’s words: "Schulman illuminates the ways in which cliques, communities, families, and religious, racial and national groups bond through the refusal to change their self-concept. She illustrates how Supremacy behaviour and Traumatised behaviour resemble each other, through a shared inability to tolerate difference.” (Schulman 2017) ↩

-

Susan Stryker, quoted in Kate Drabinski, “Identity Matters: Teaching Transgender in the Women’s Studies Classroom”, The Radical Teacher, No. 100 (Fall 2014): 143. DOI 10.5195/rt.2014.170. ↩

-

A study “Health, disability and quality of life among trans people in Sweden – a web-based survey” (Zeluf 2016, 8) found that out of 756 trans*people (the categories in the survey comprised transmasculine, transfeminine, gender non-binary and transvestites) 80% of the non-binary participants experience poor health. Out of all the participants, 53% reported having some kind of disability. “Moreover, our results demonstrate that lack of legal gender recognition and history of negative healthcare experiences due to trans-incompetence or transphobia in the healthcare system, are important predictors of worse self-rated health, increased self-reported disability and lower quality of life among study participants.” In France, official statistics concerning the health of the trans*community are sparse. However we found the 2011 report “Inspection générale des affaires sociales- RM2011-197P” with the title “Evaluation des Conditions de prise en charge médicale et sociale des personnes trans e de transsexualisme”, commissioned by the French Government and evaluating the medical care the trans*community in France receives. (https://www.vie-publique.fr/sites/default/files/rapport/pdf/124000209.pdf)