Throughout the TTTT programme there were several moments of collective reflection, some instigated by the participants, some by the organizers. We list these “check-in moments” at specific points in time here in chronological order and link to the respective documents.

The main part of this page is concerned with the one-day Reflection Workshop facilitated by cultural worker Teresa Cisneros.1 towards the end of the programme in December 2021. You find the short version of this collective reflection in the Reflection Workshop Summary summarized by Femke Snelting 2 coming to this task with fresh eyes. This summary will give the reader an overview of the pitfalls, tensions and successes of the programme both from the participants and organisers perspectives in the hope others can learn from us and our mistakes. The workshop’s method could also be applied in similar situations, when a collective reflection is needed.

The summarized transcript is followed by the annotated and copy-edited Reflection Workshop Transcript. This original record invites the reader into the richness and diversity of voices and experiences made, describing the take-aways, the thank-yous, next to articulating frustrations and highlighting the programme’s contradictions.

Timeline, Collective Moments of Reflection

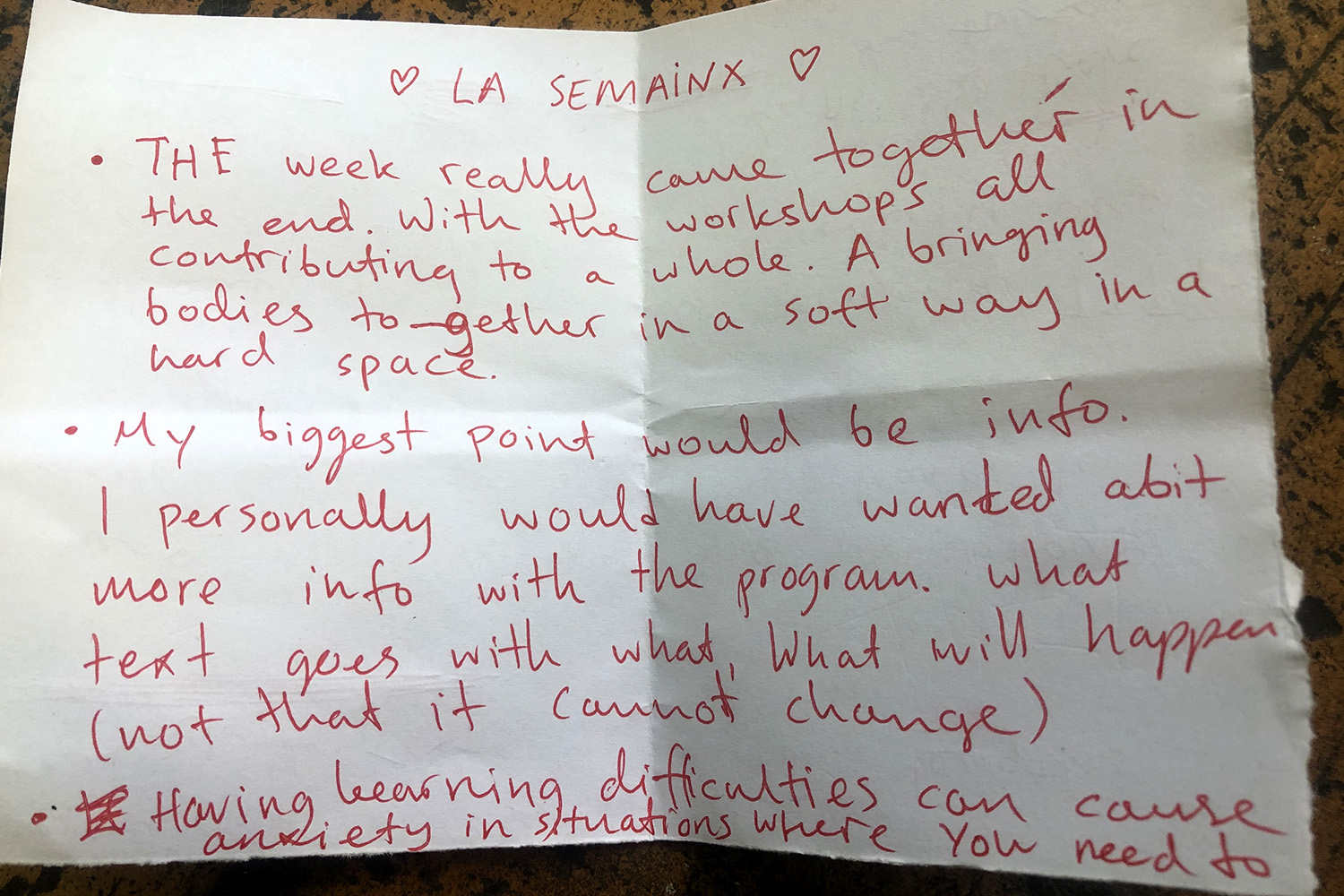

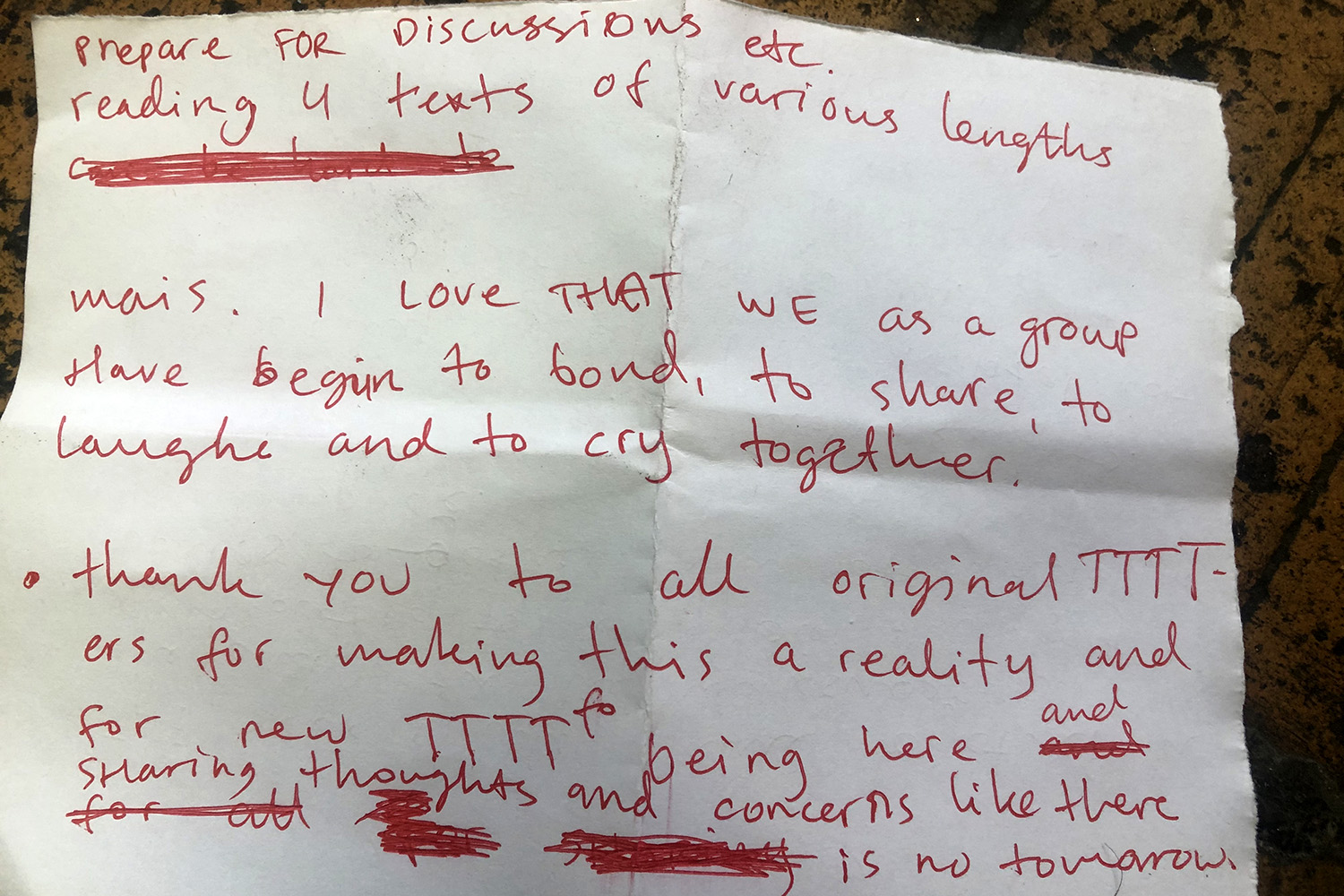

Checking-out, Jan 2020

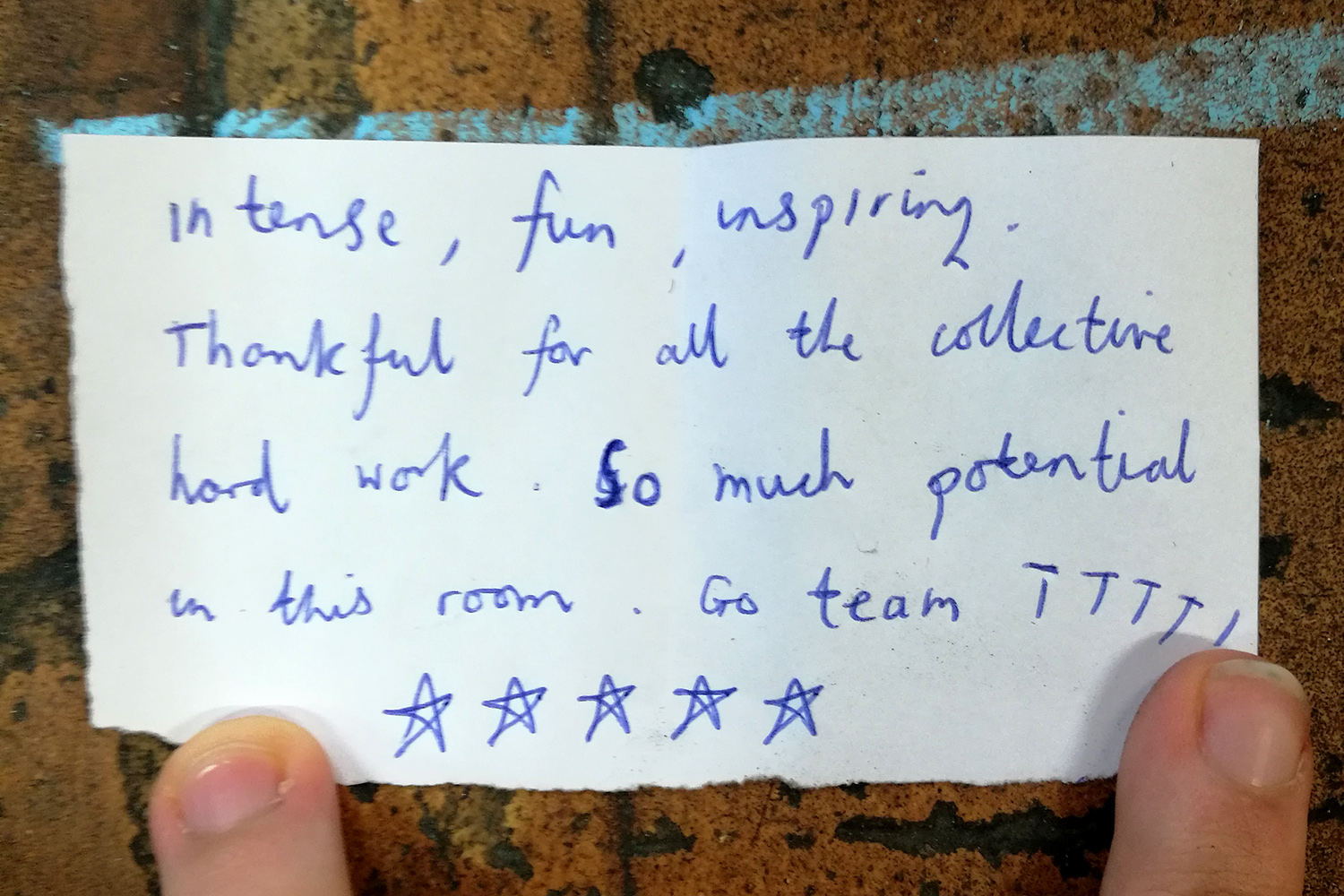

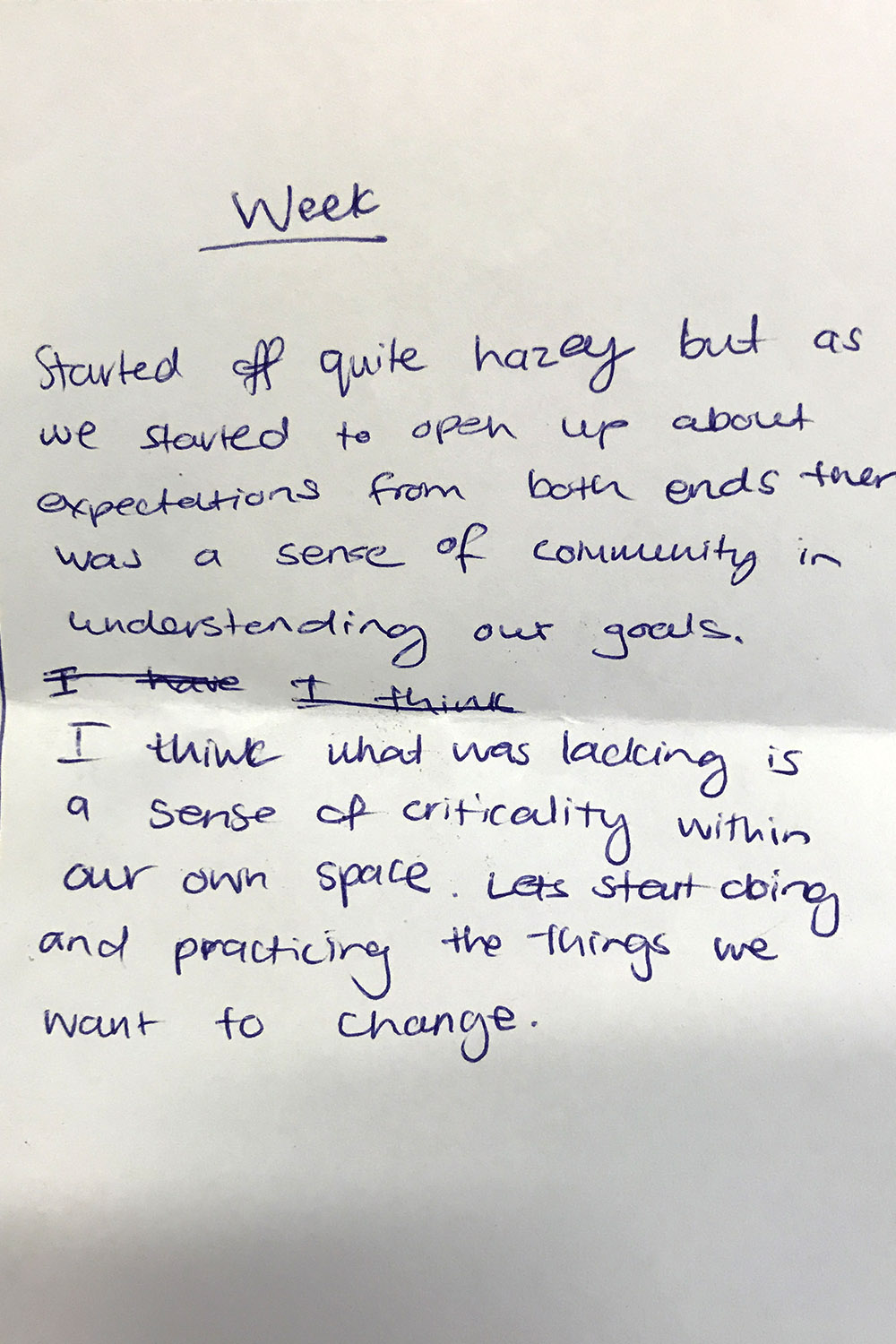

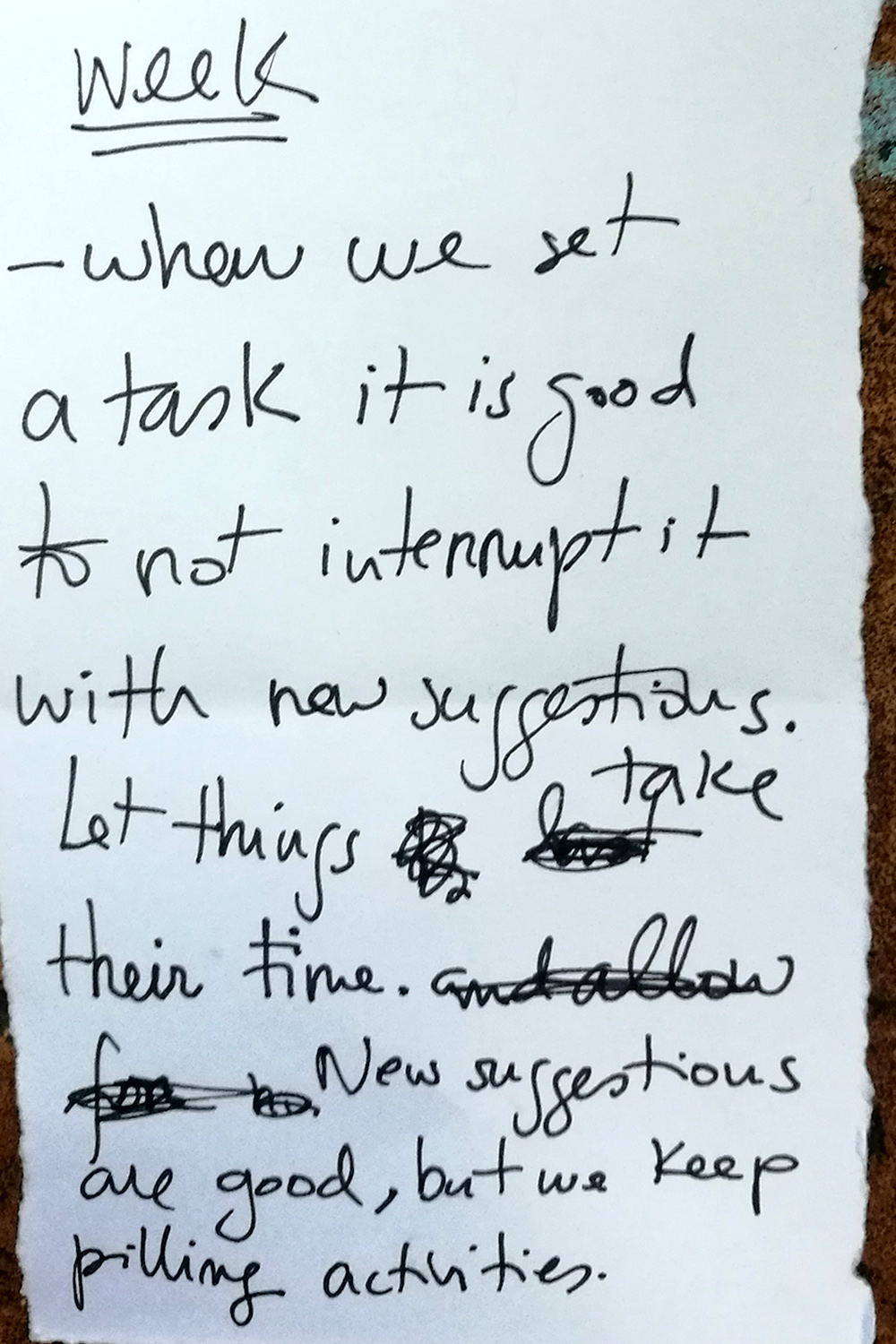

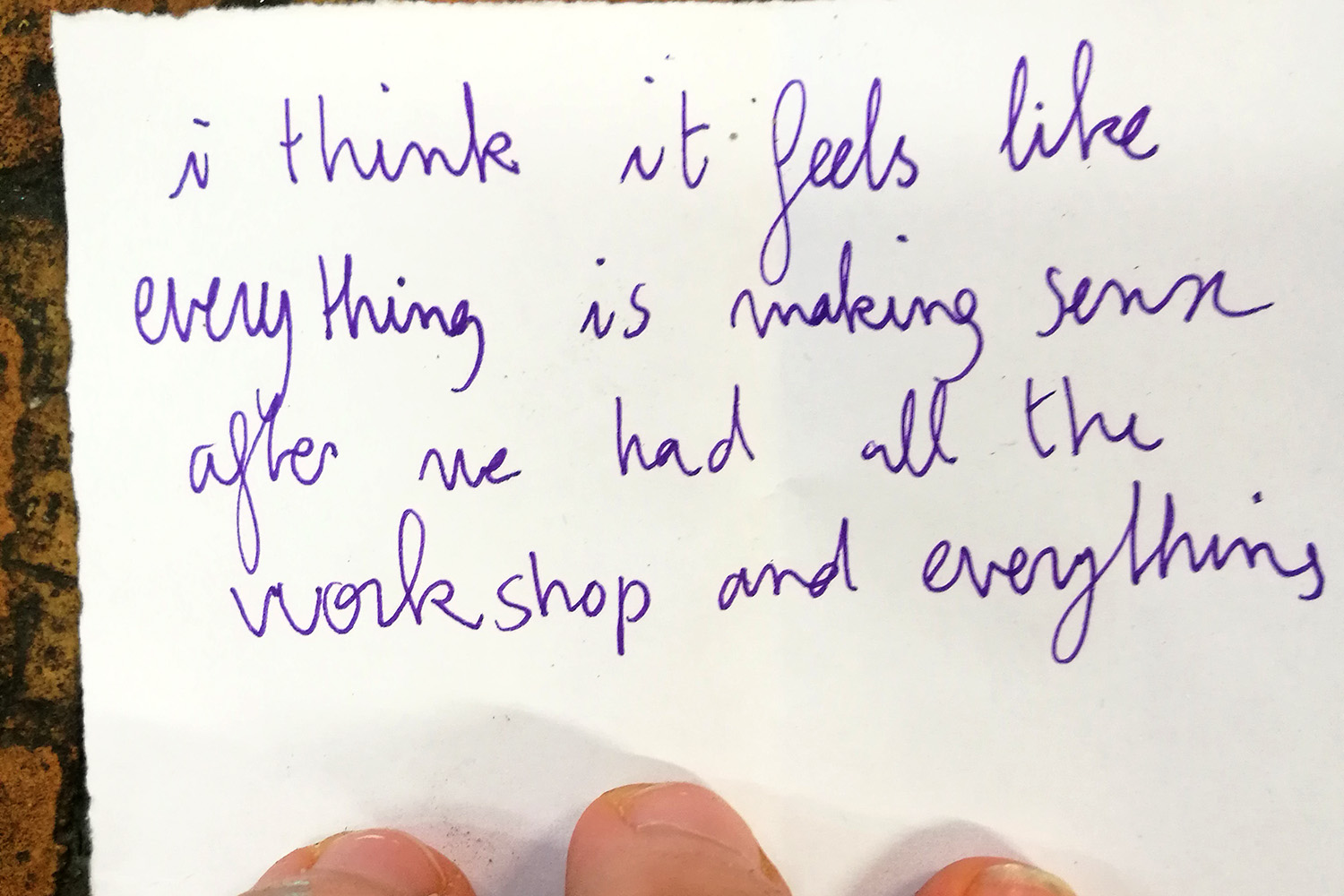

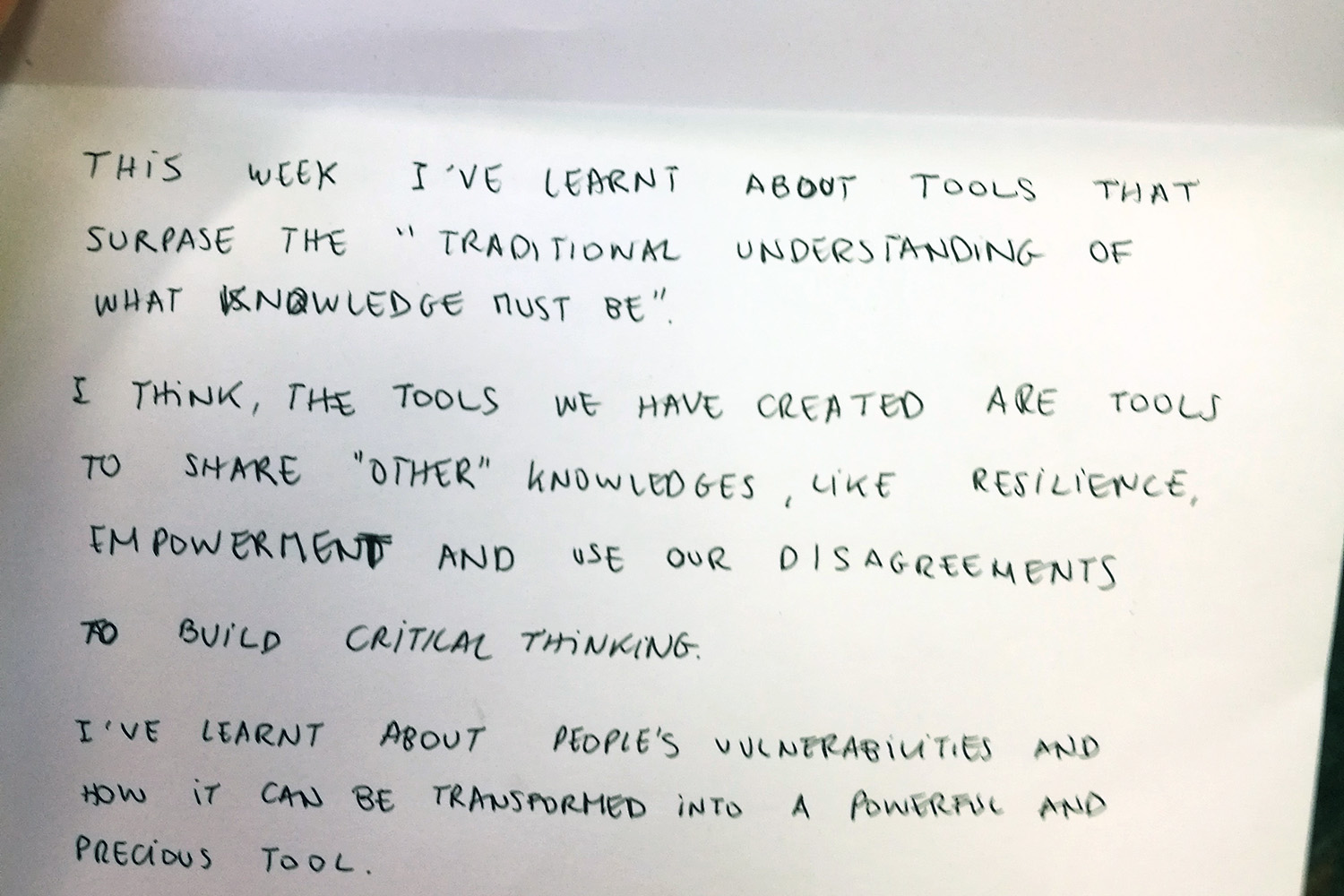

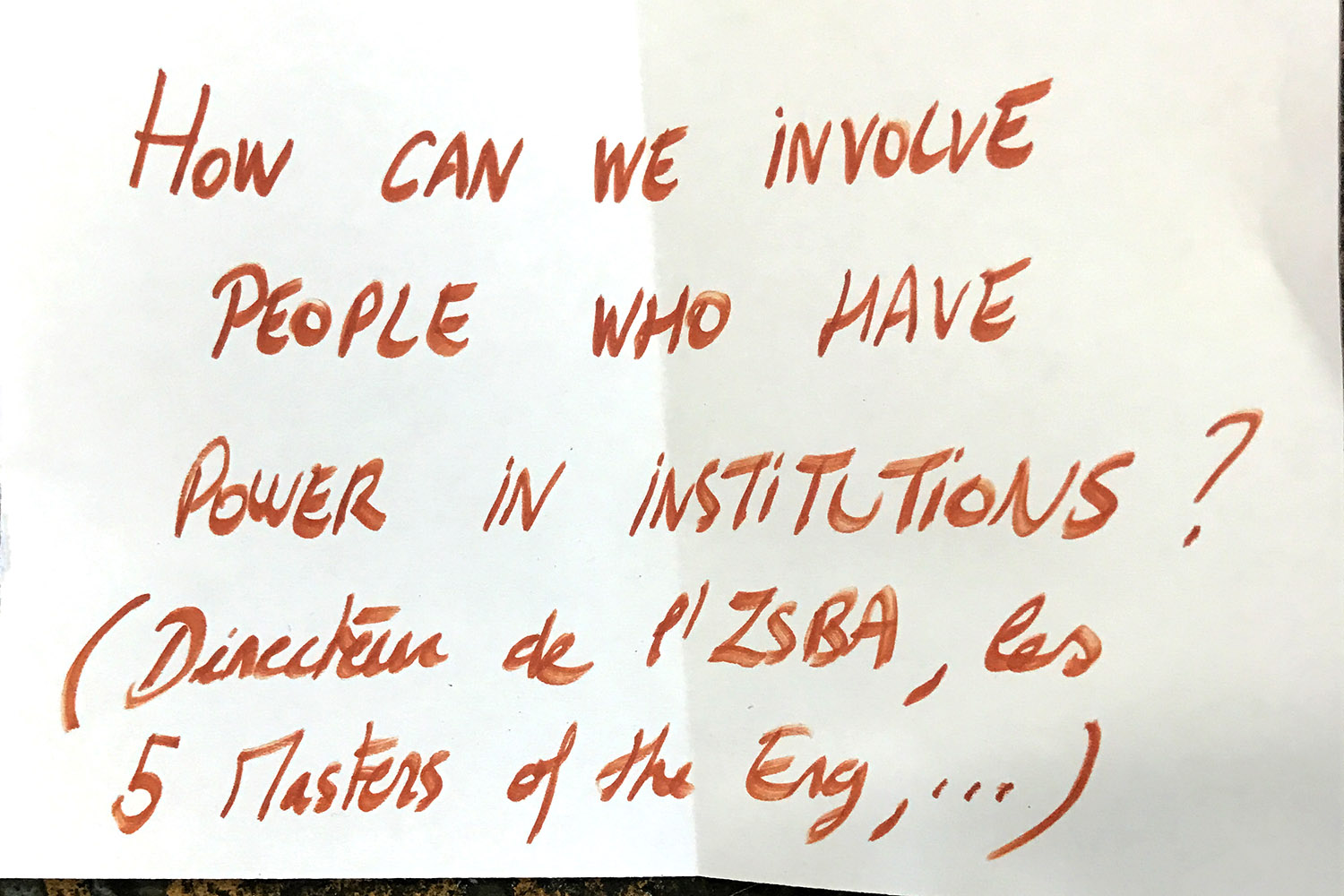

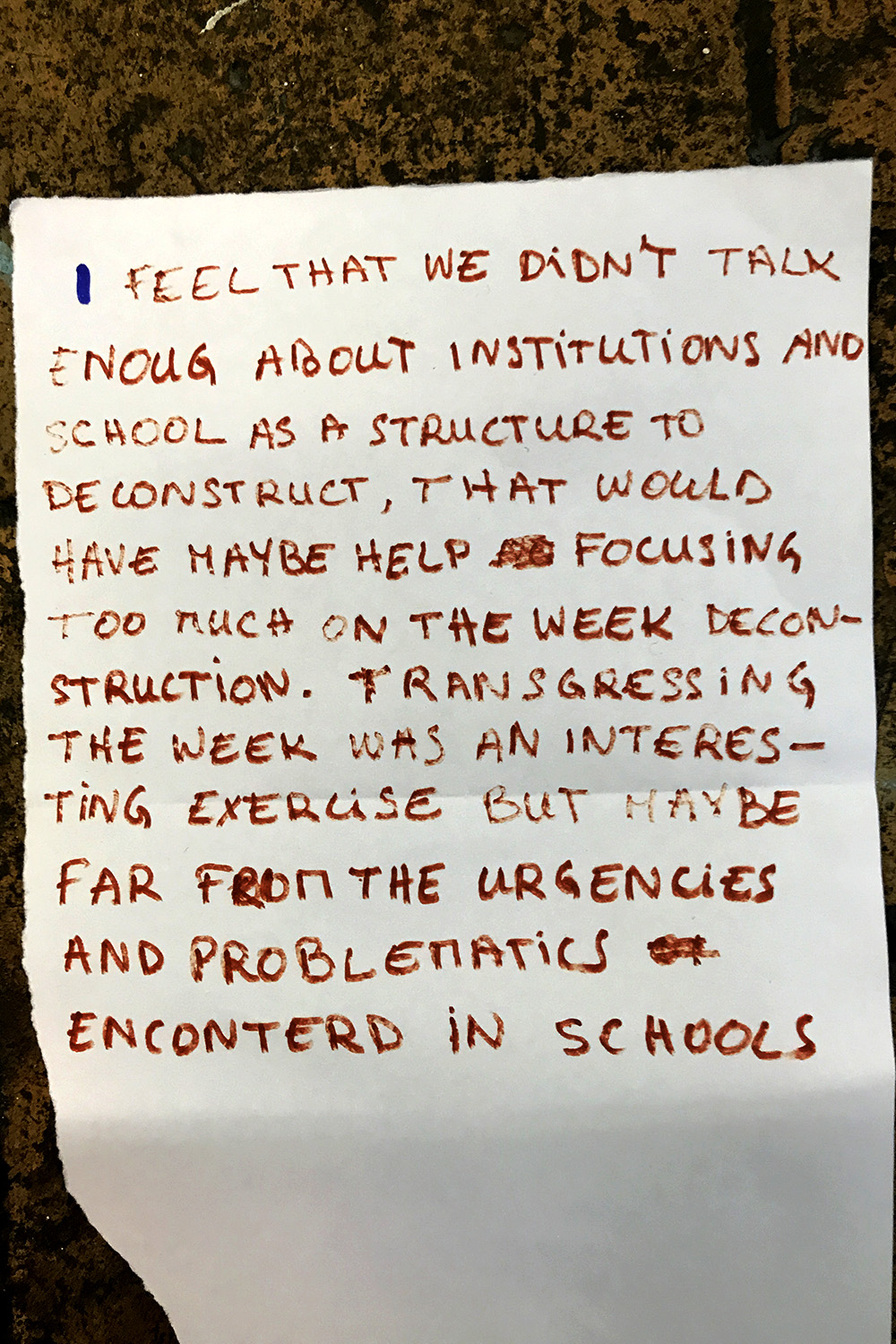

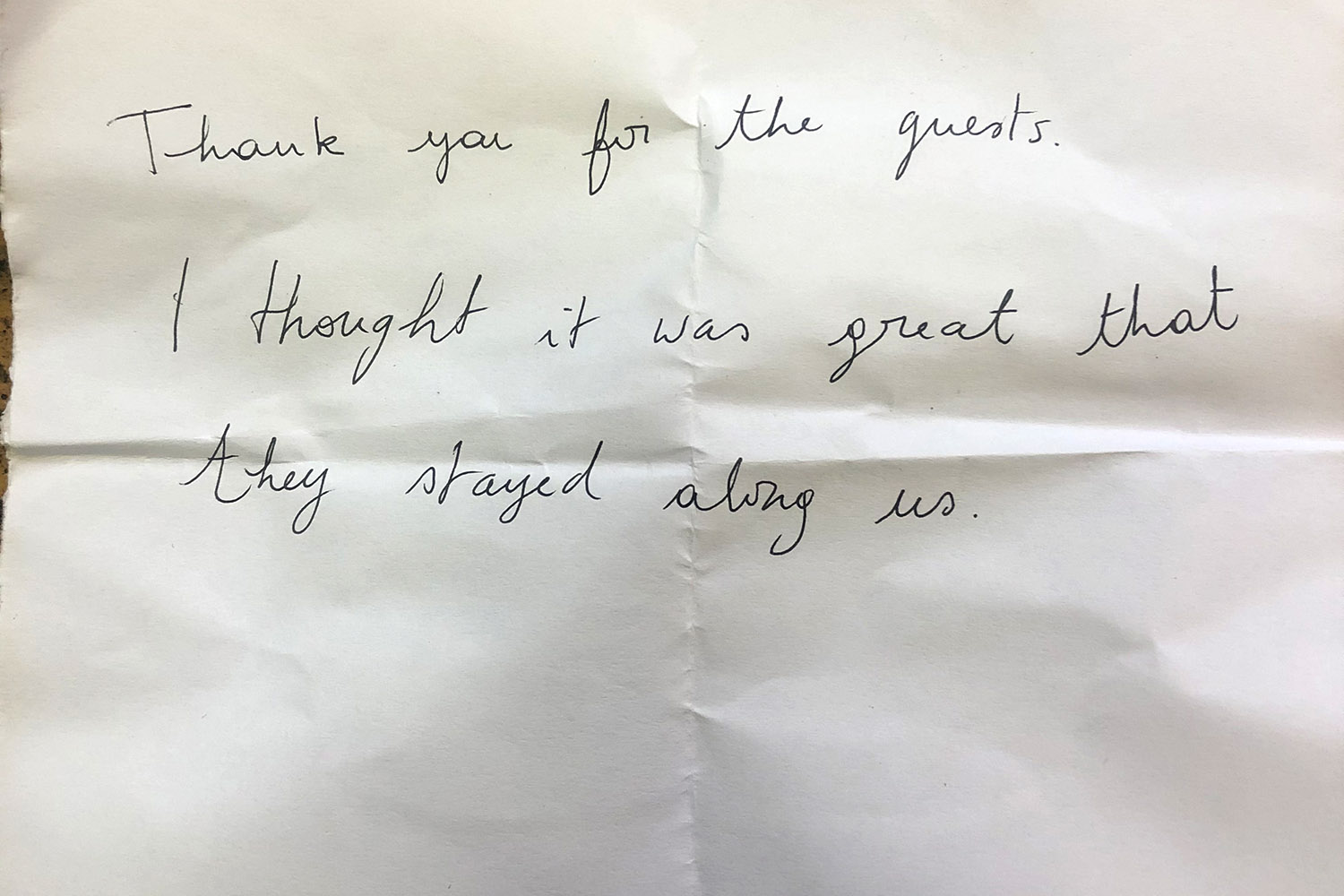

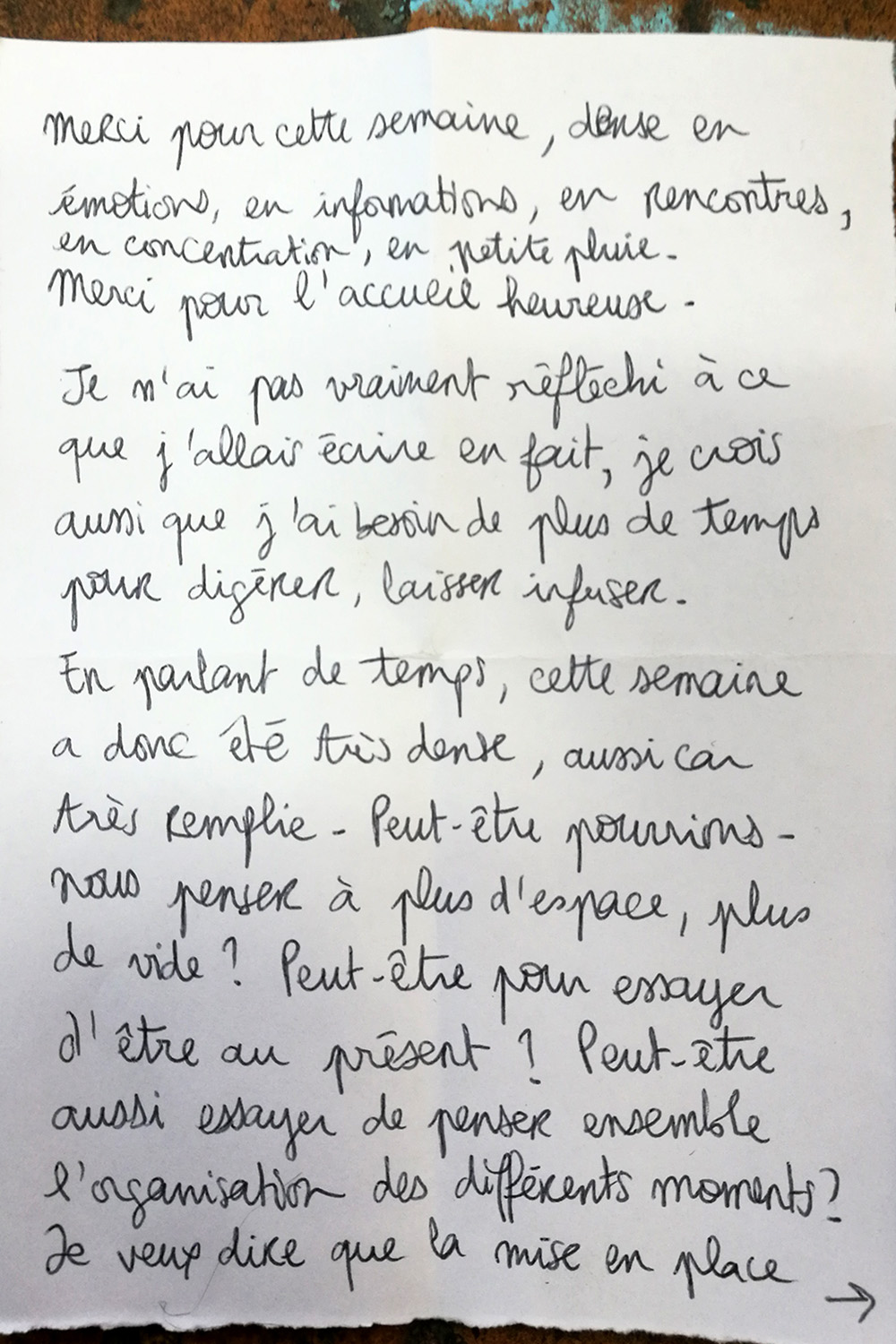

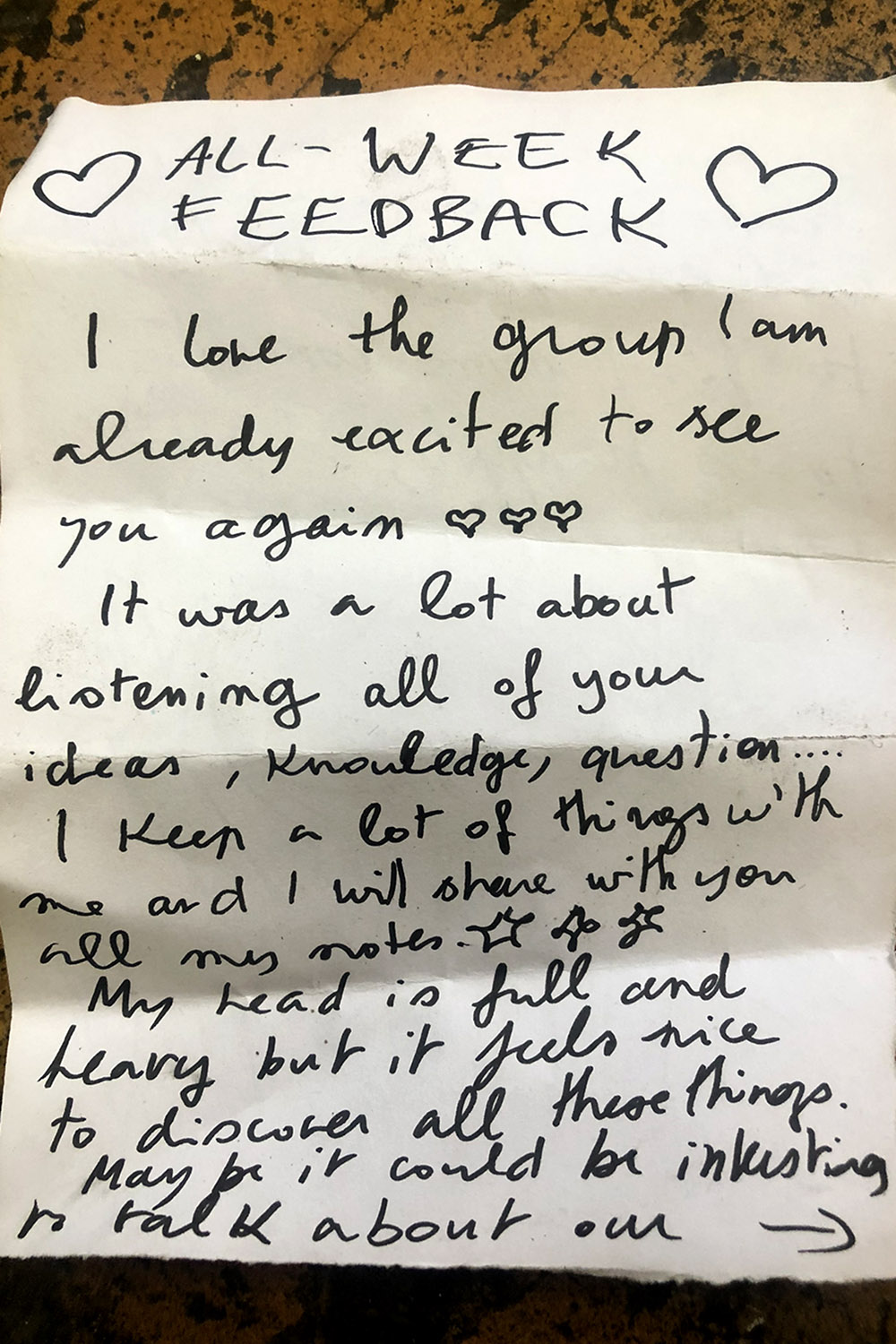

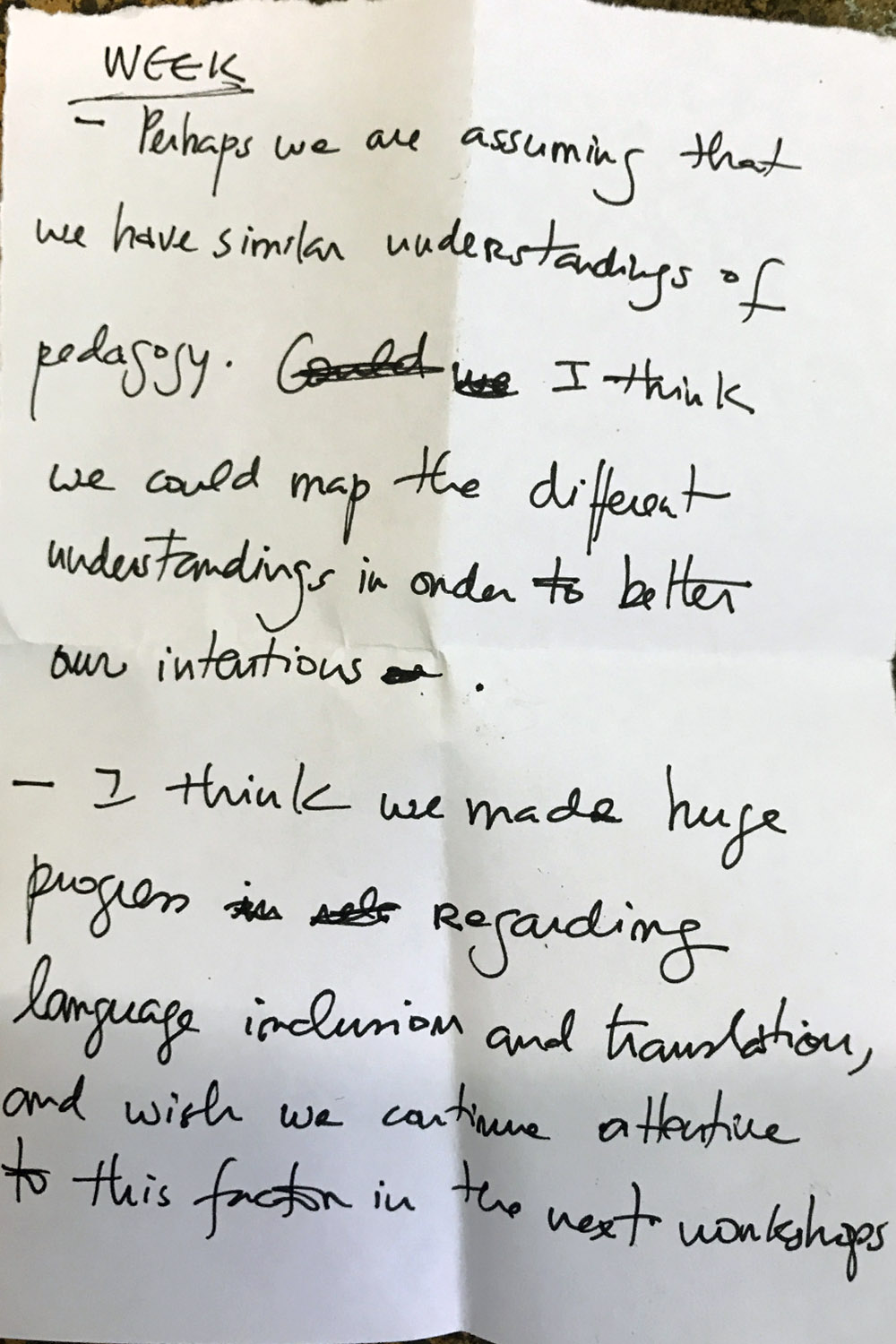

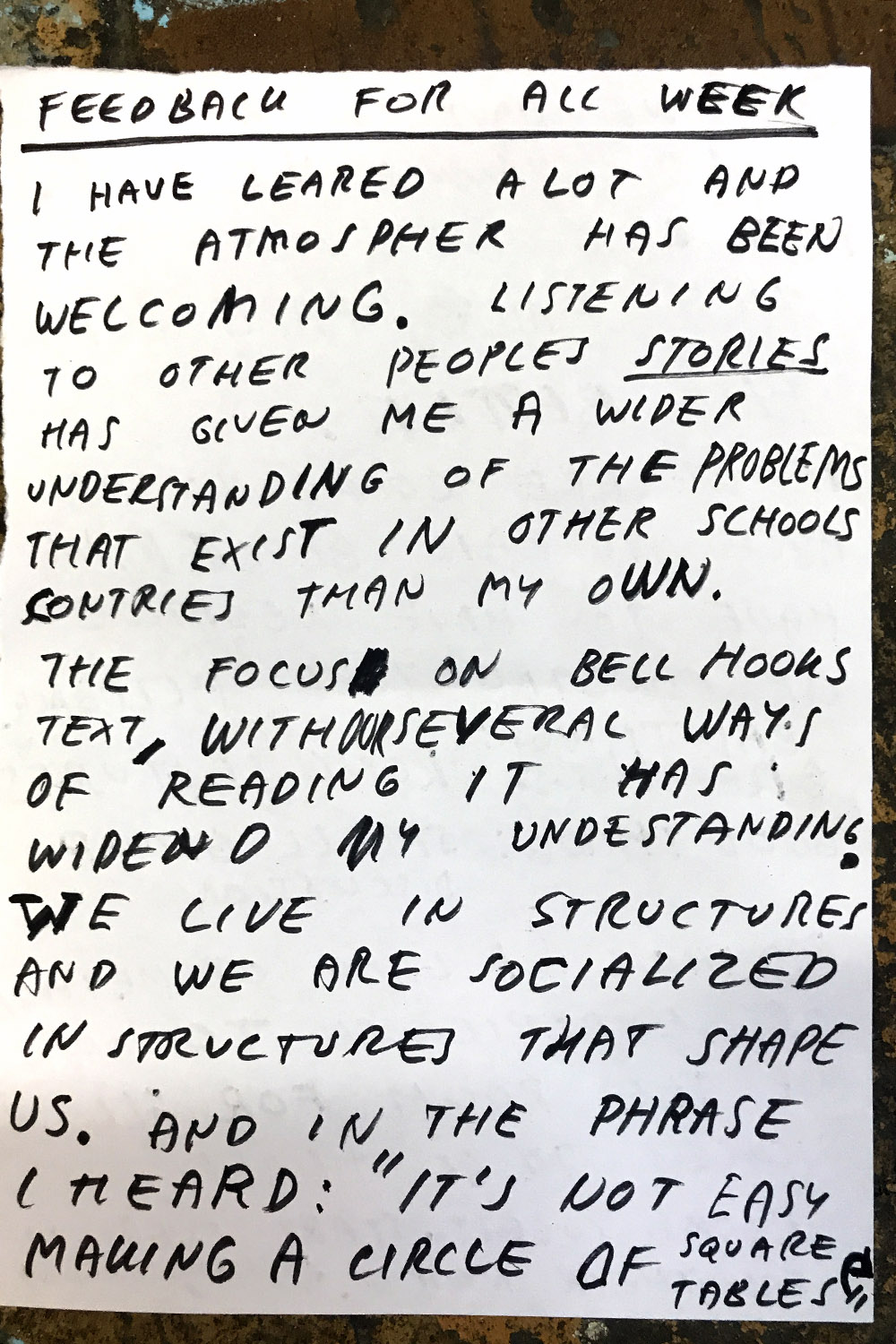

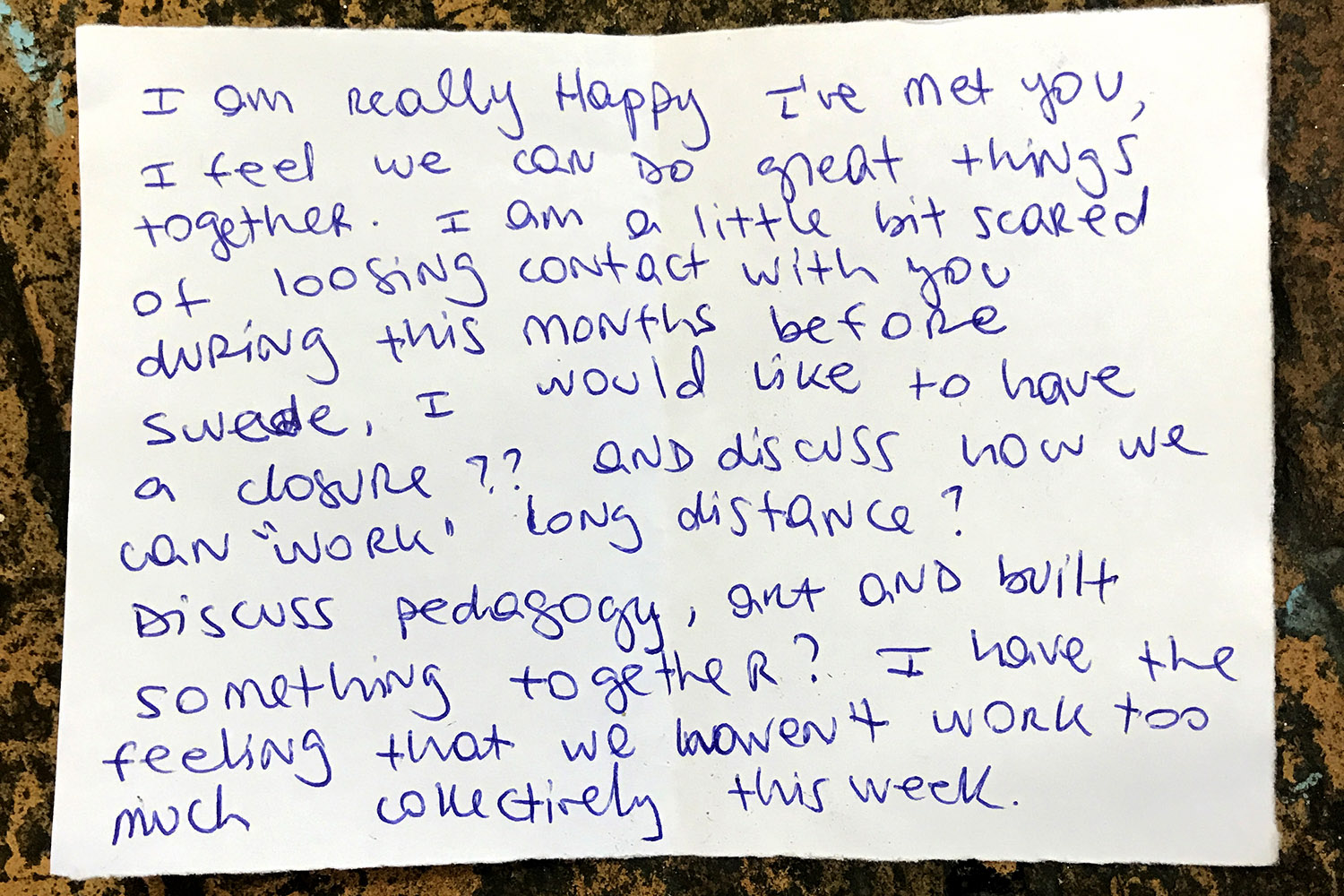

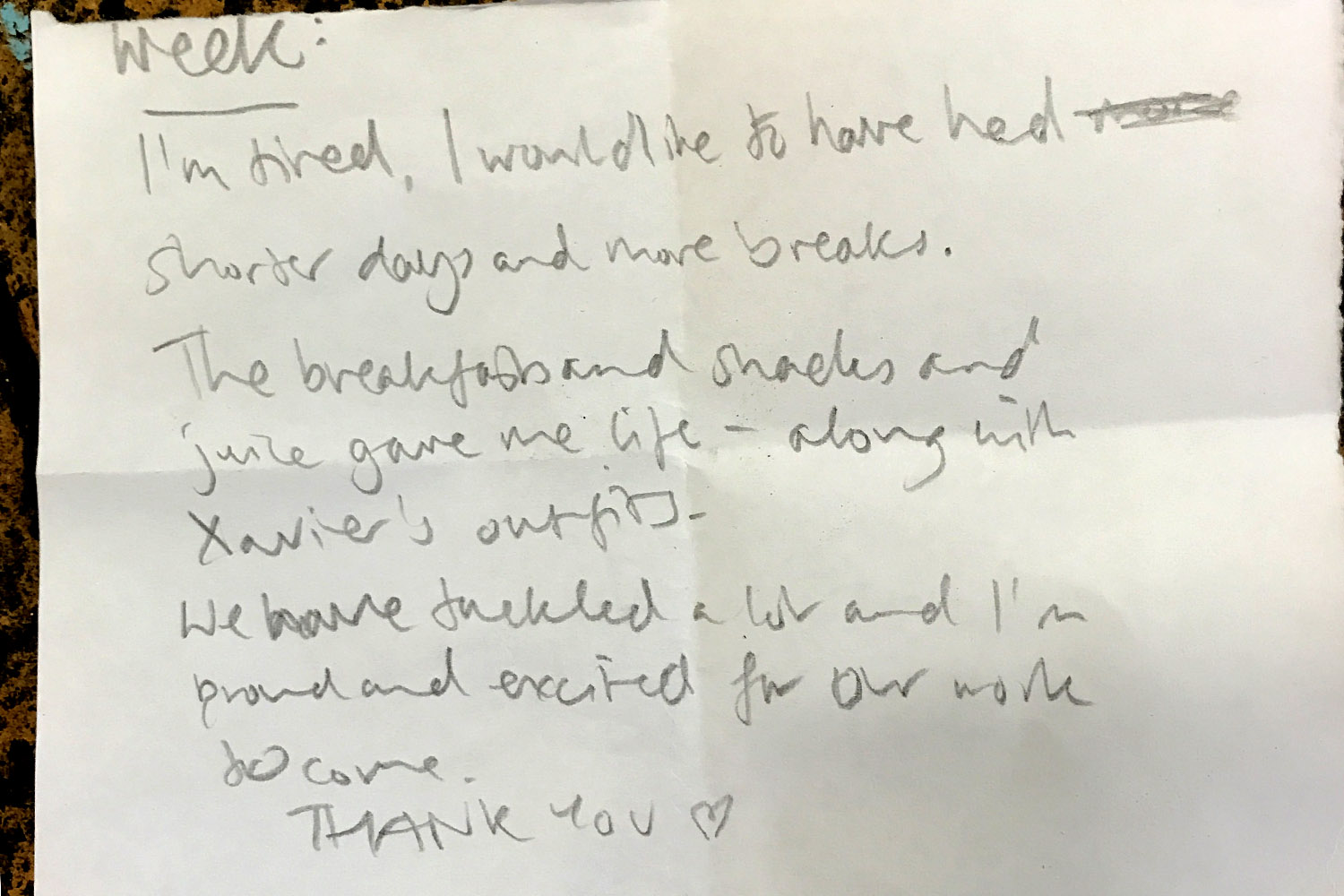

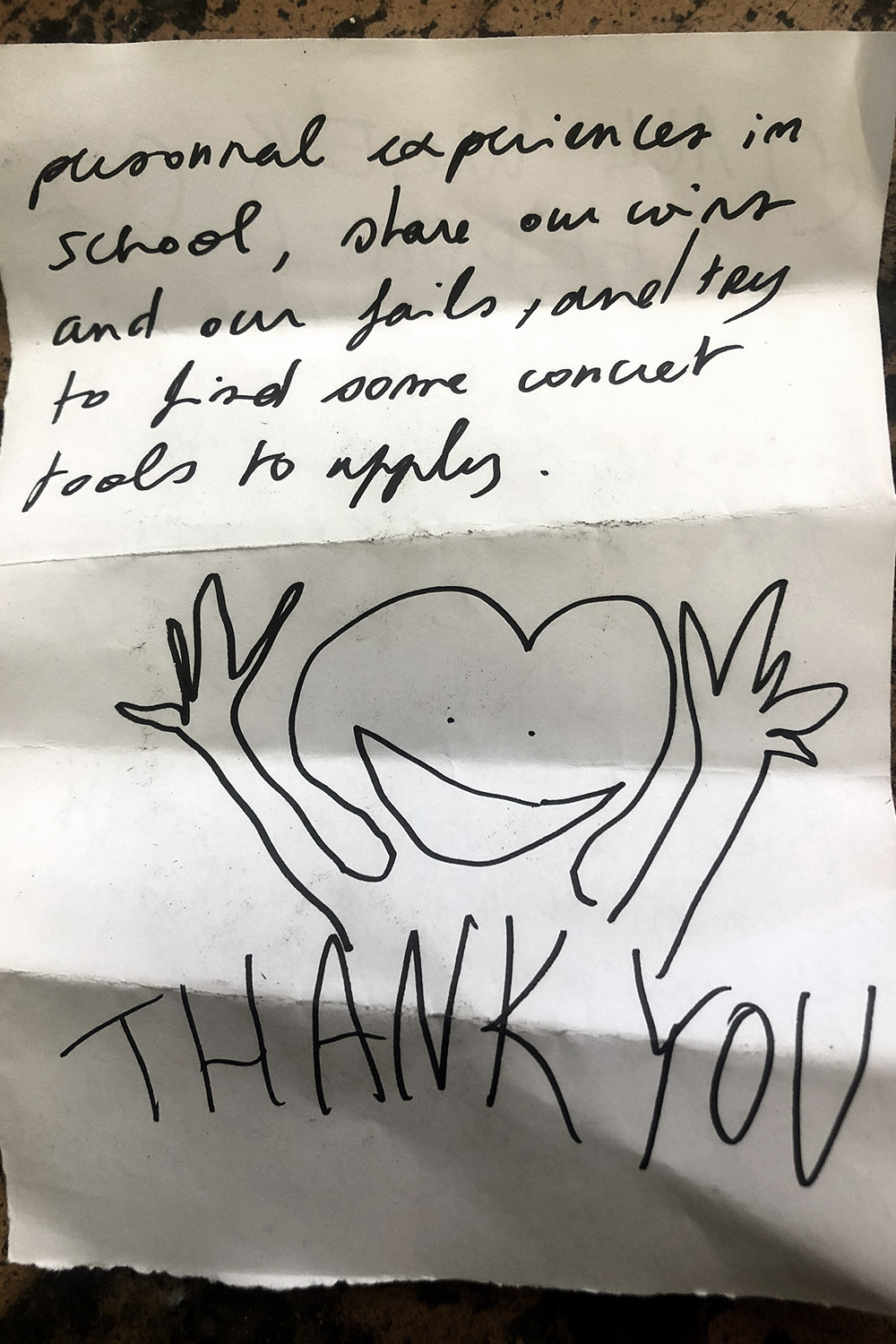

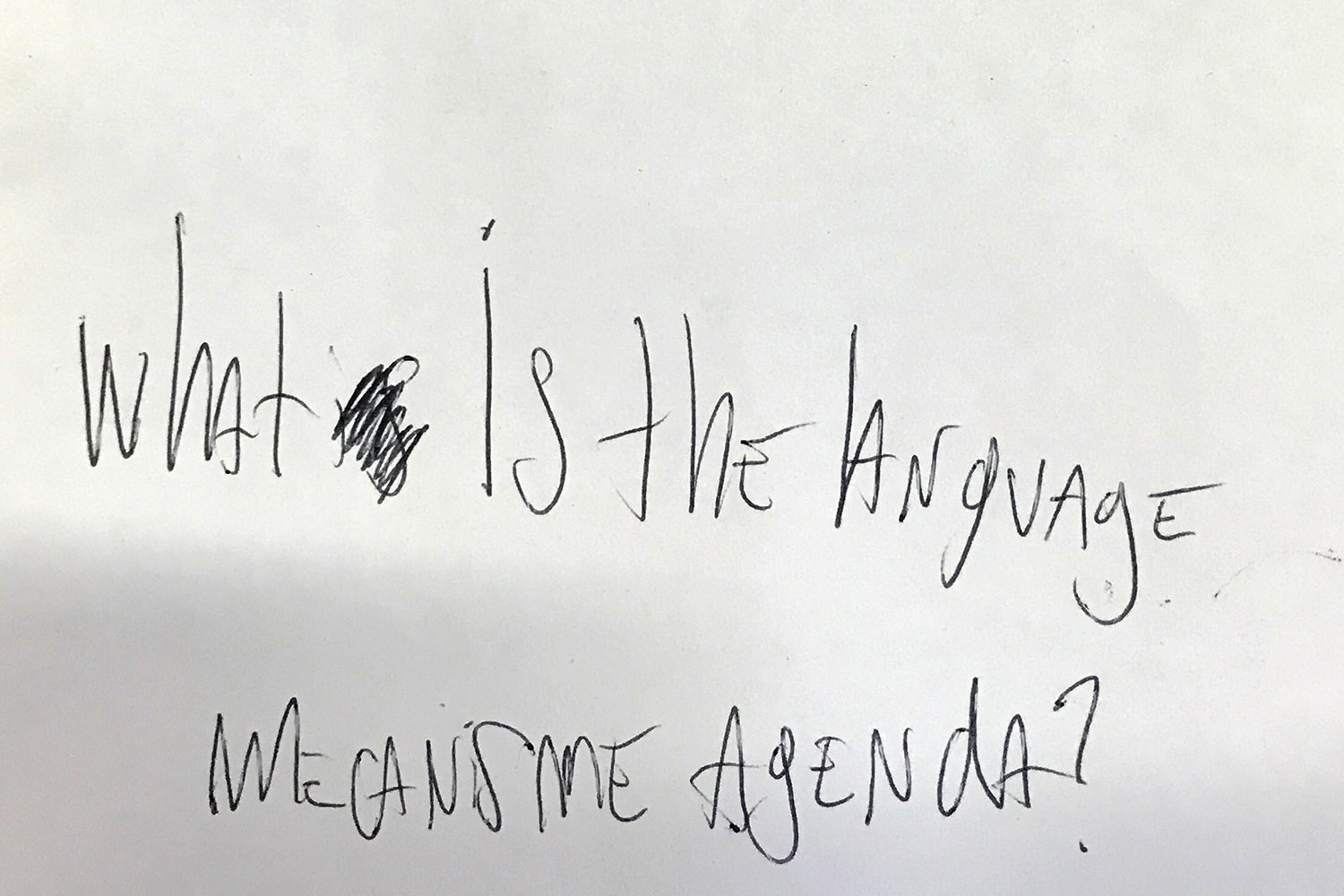

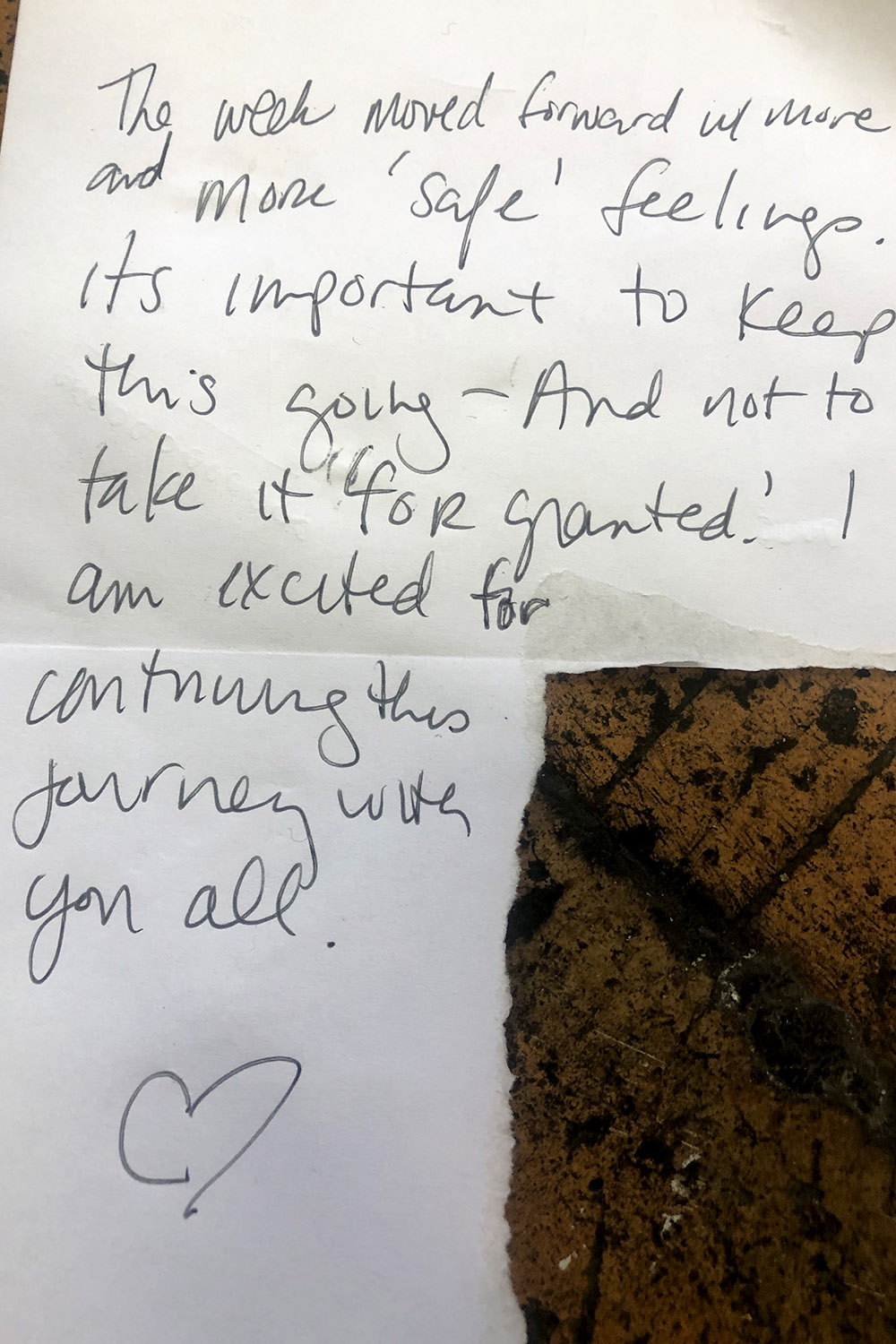

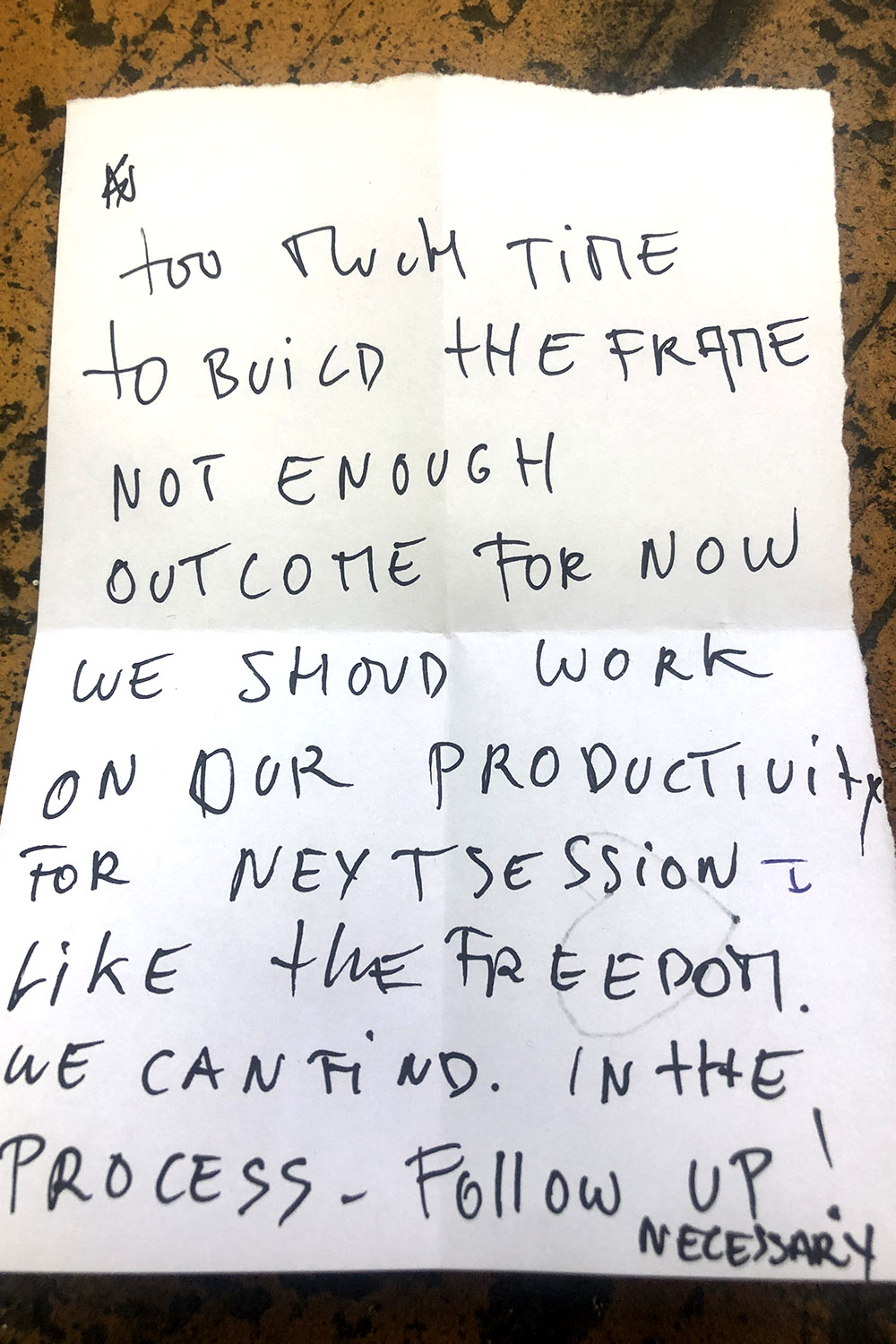

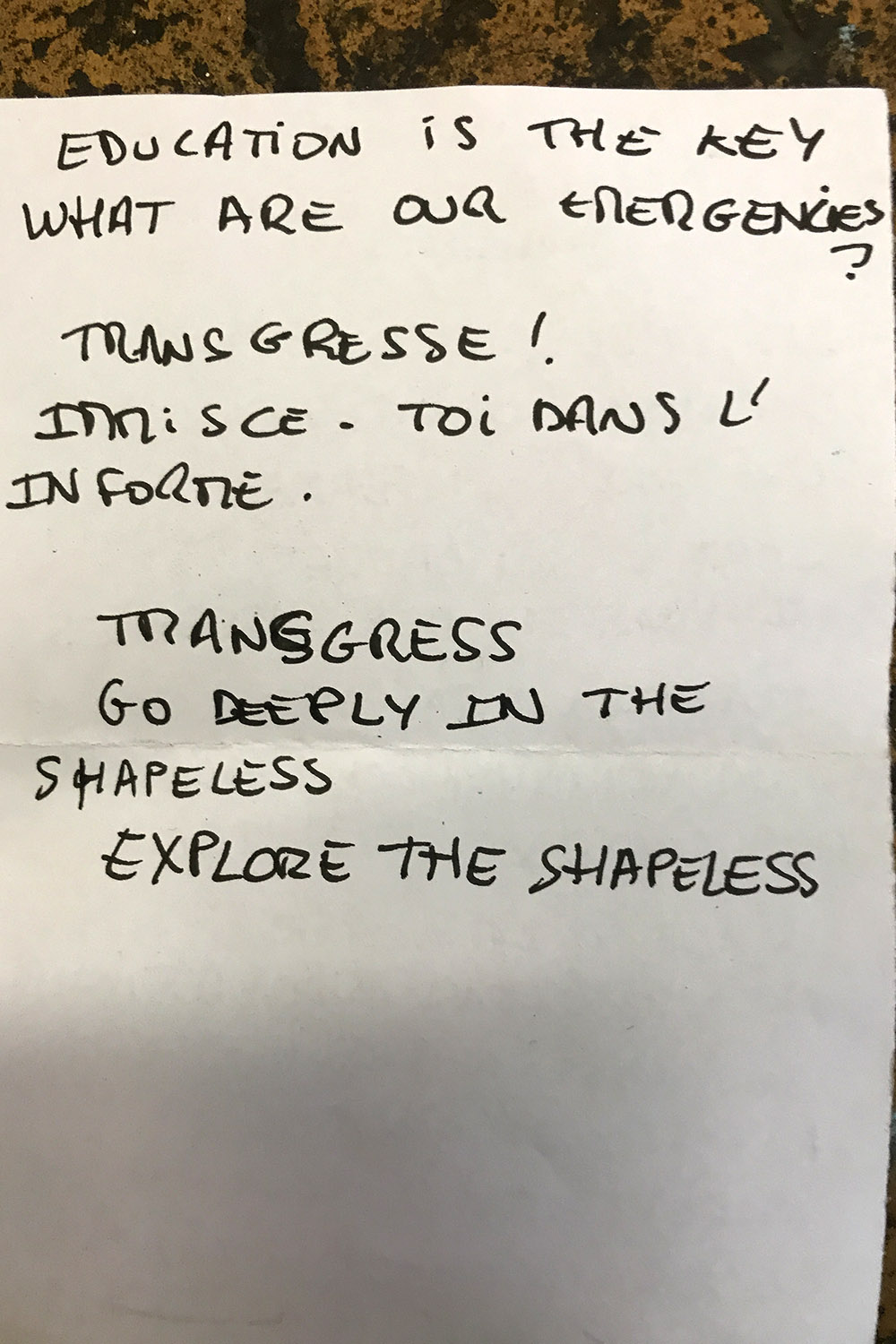

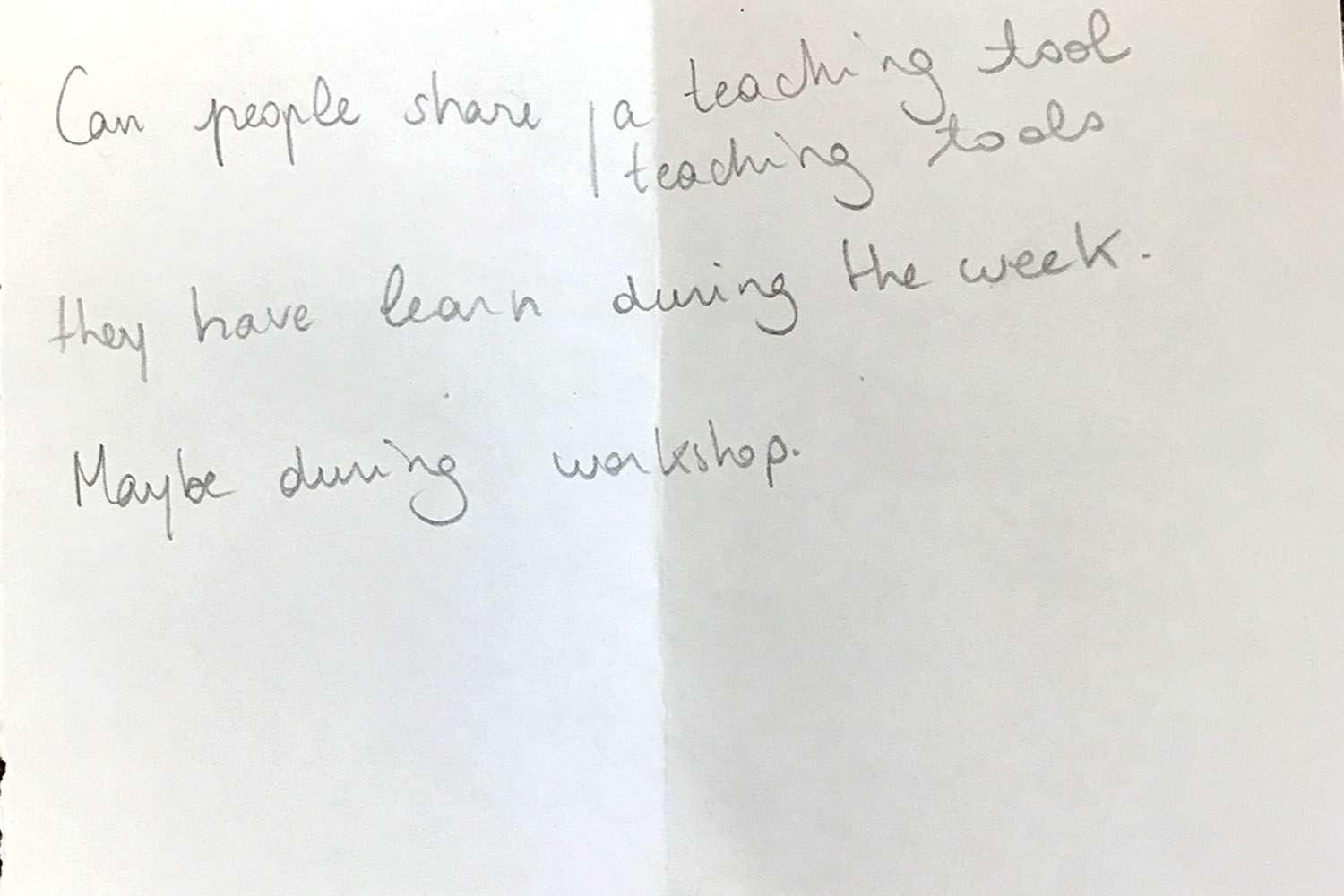

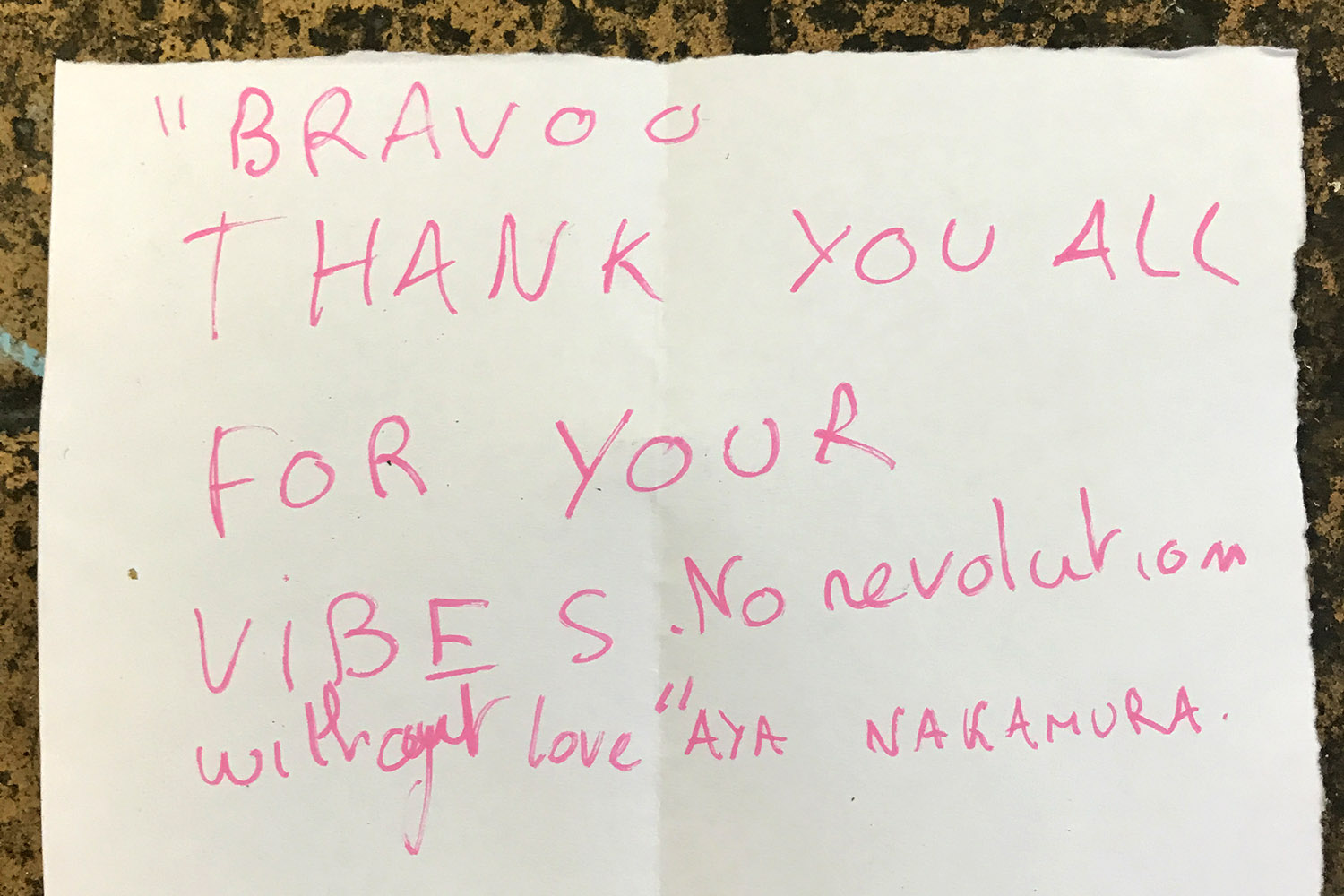

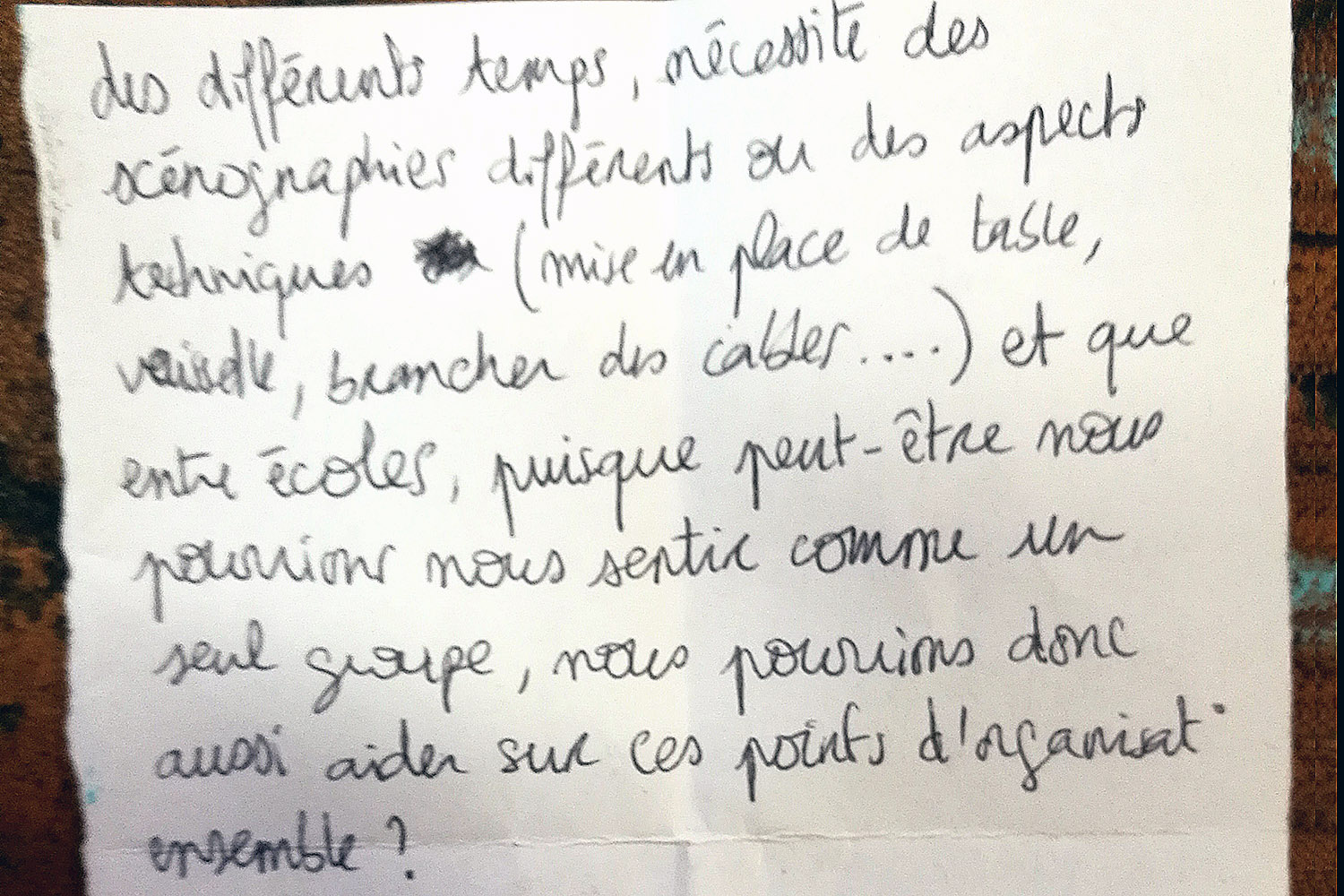

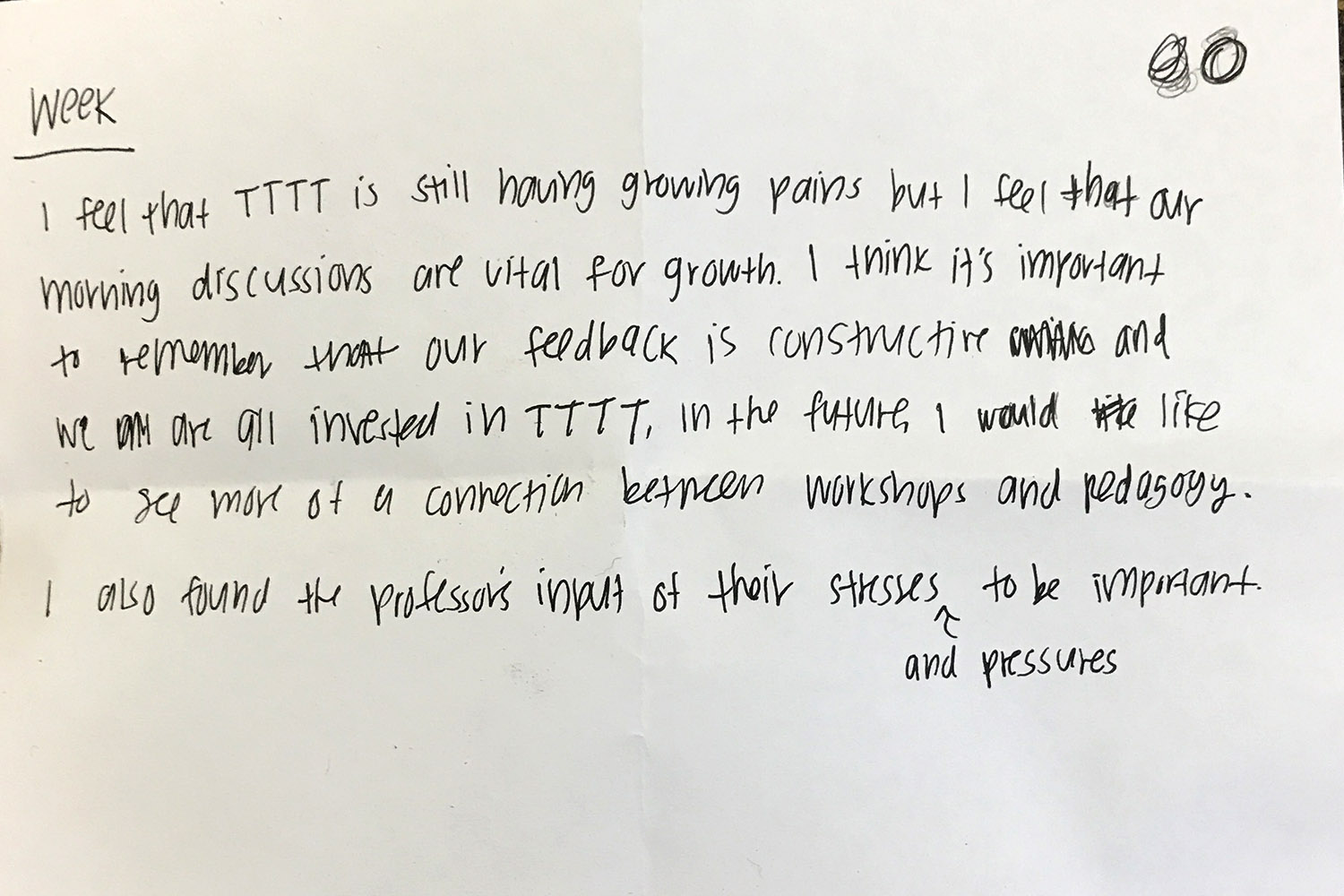

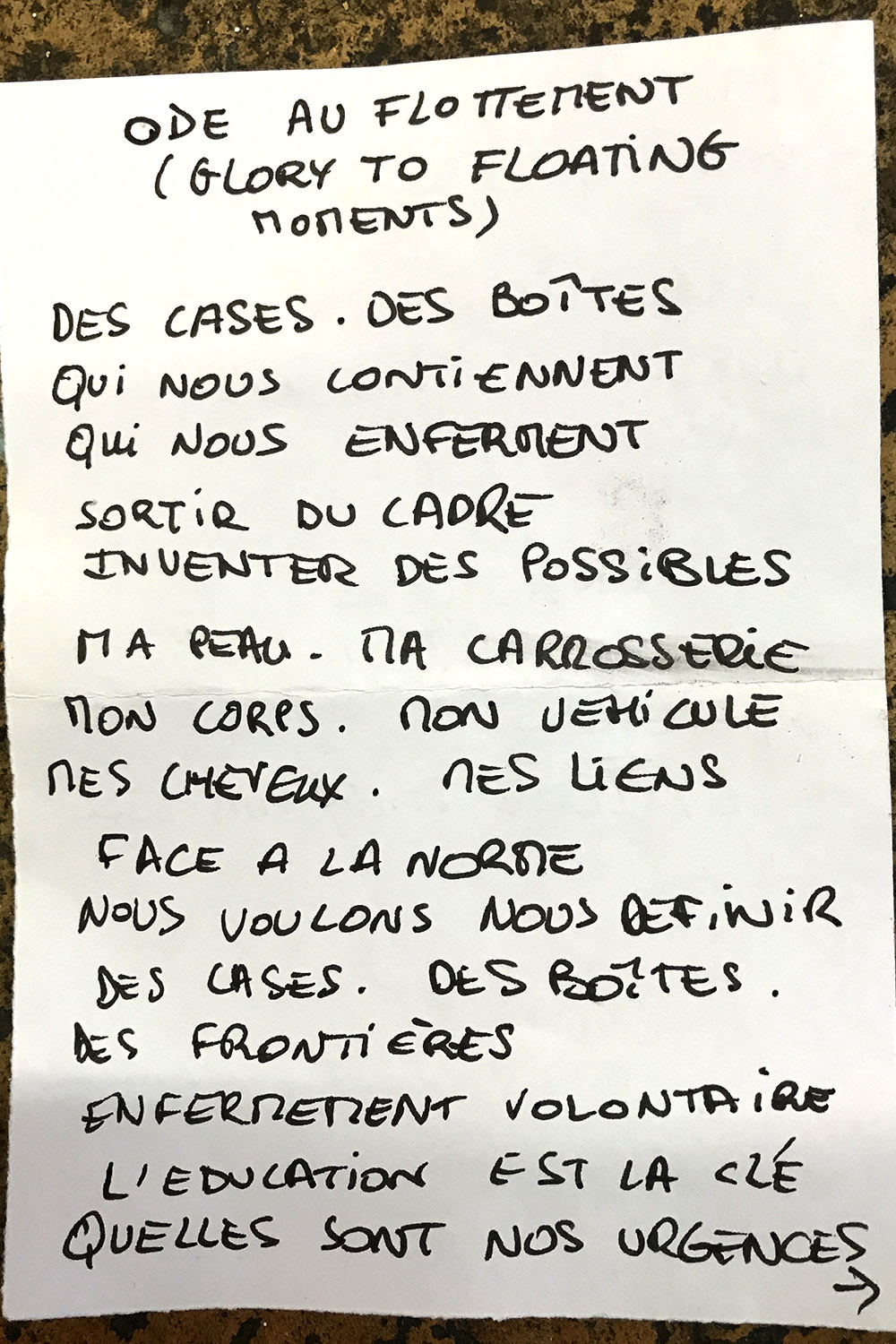

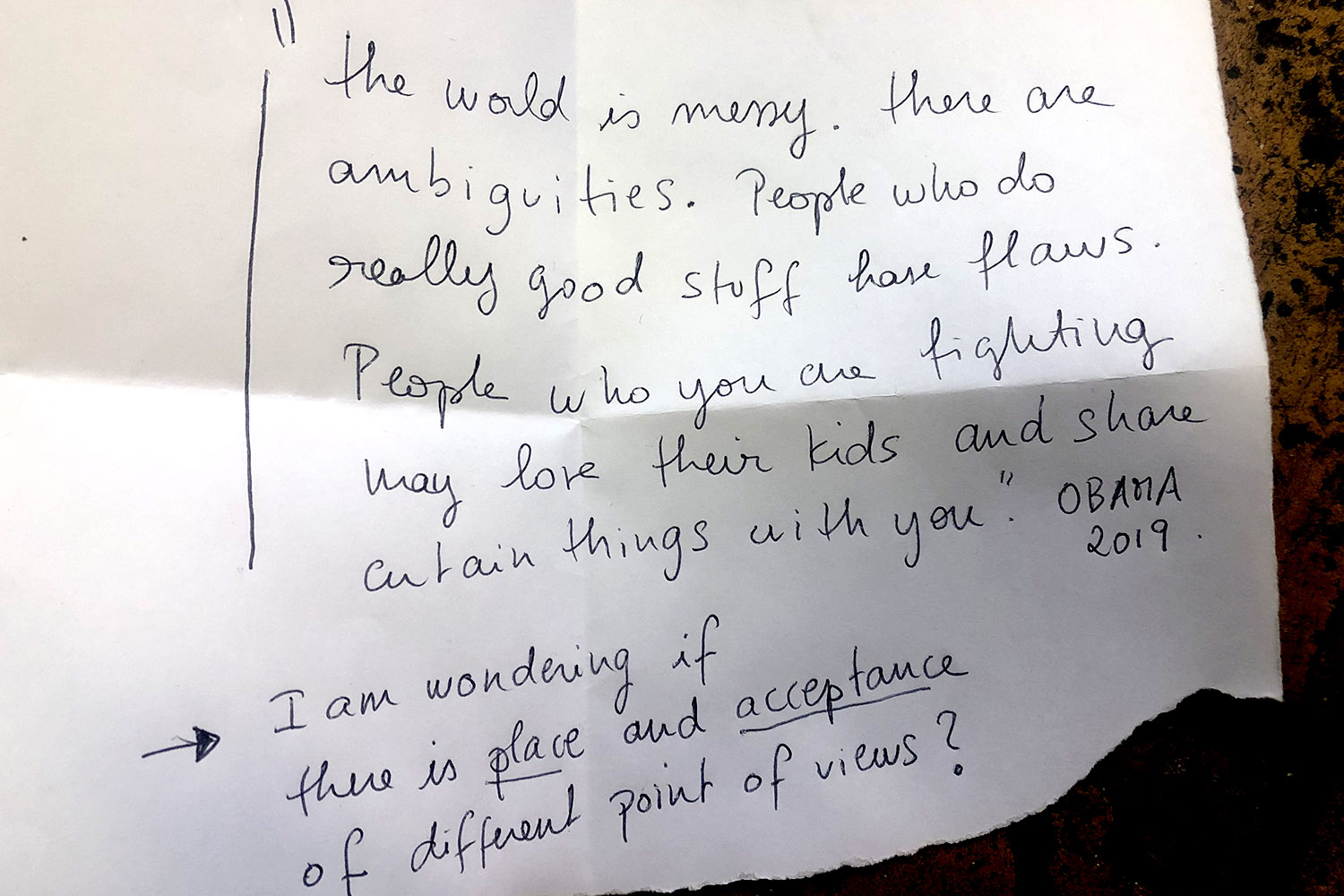

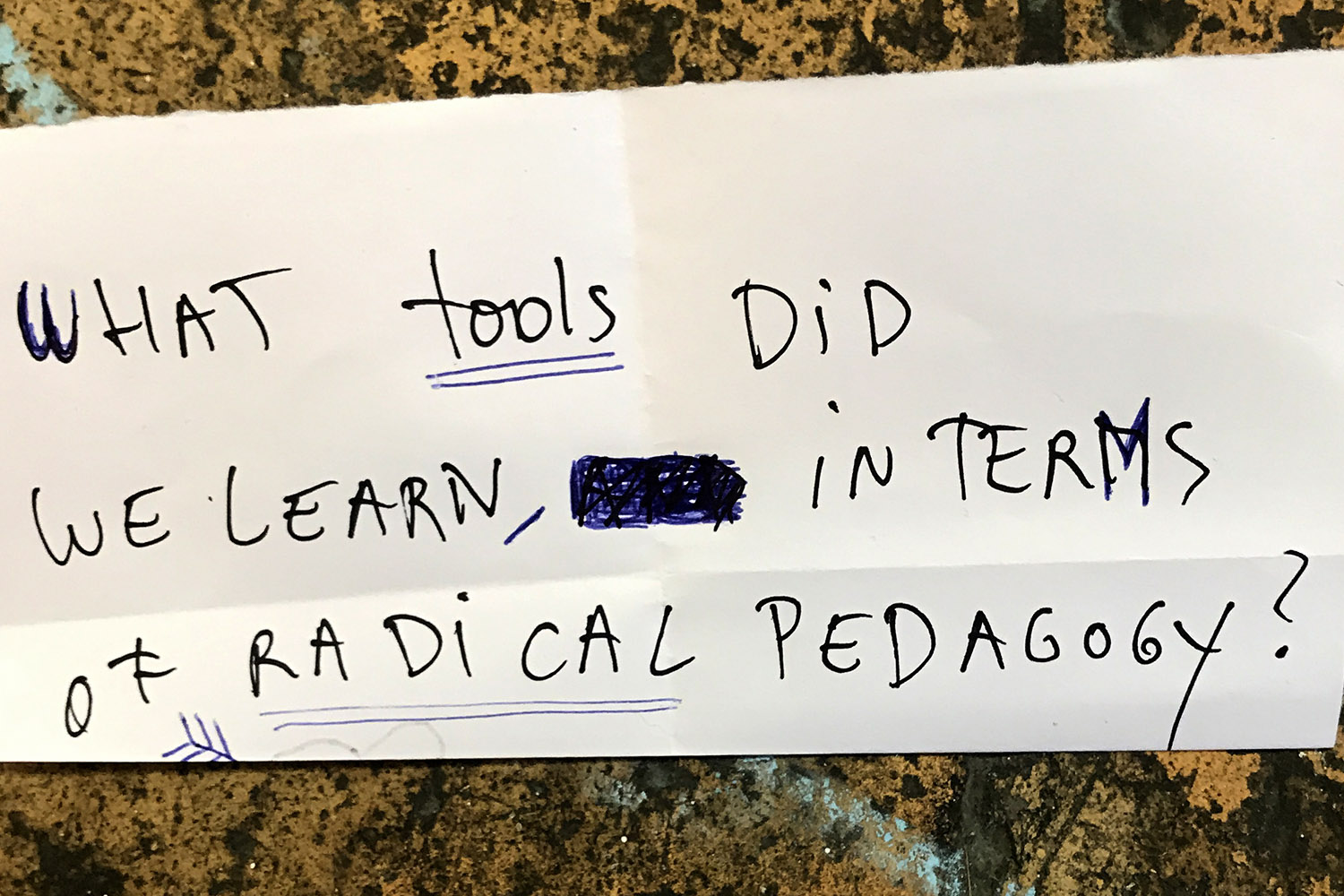

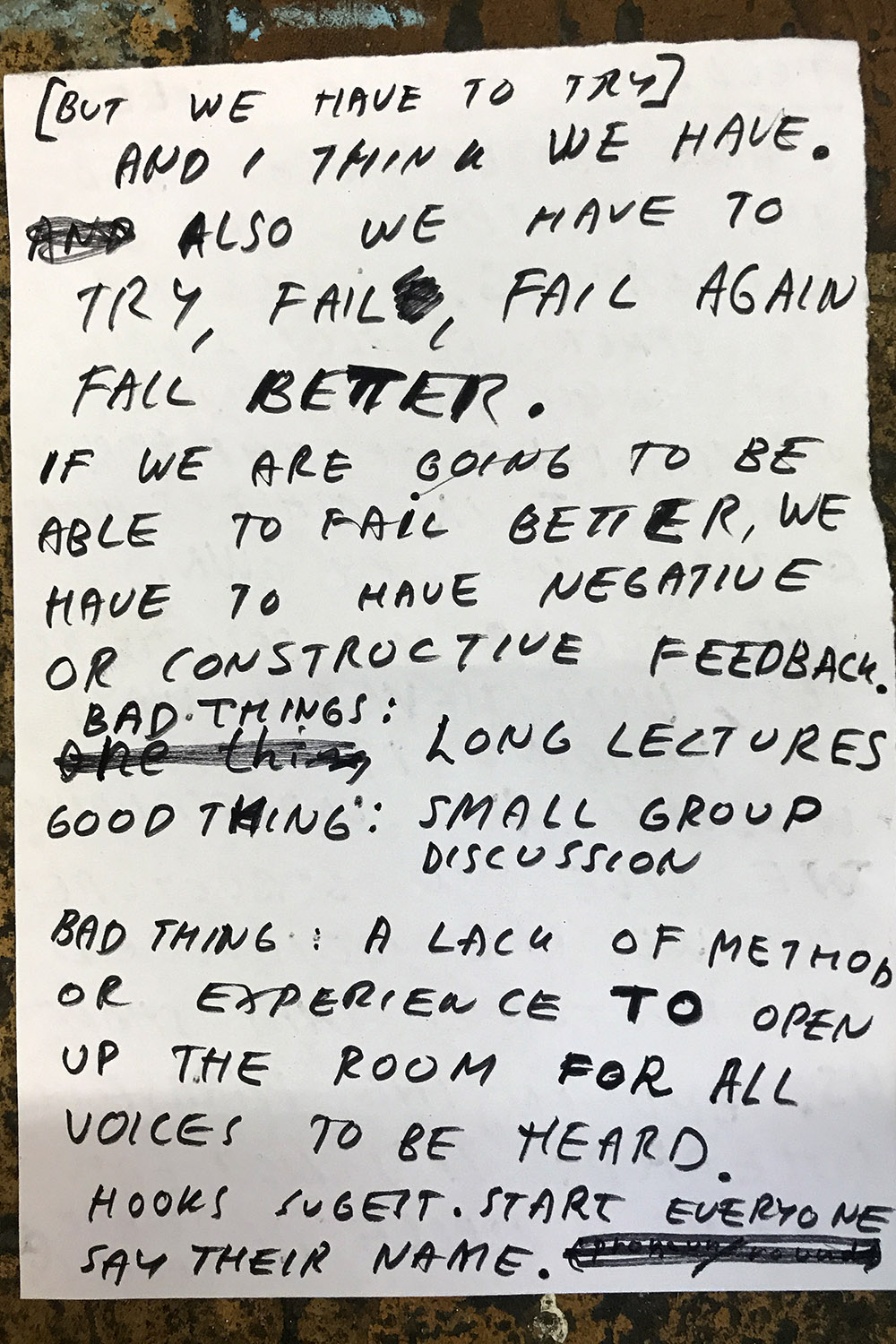

The first collective moments of reflection took place in Brussels, where we had our first and only in-person worksession in January 2020 — just before the pandemic hit. On January 31, 2020, the last day of this one-week gathering, participants and organisers wrote feedback on scraps of paper reflecting on the week that we spent together.

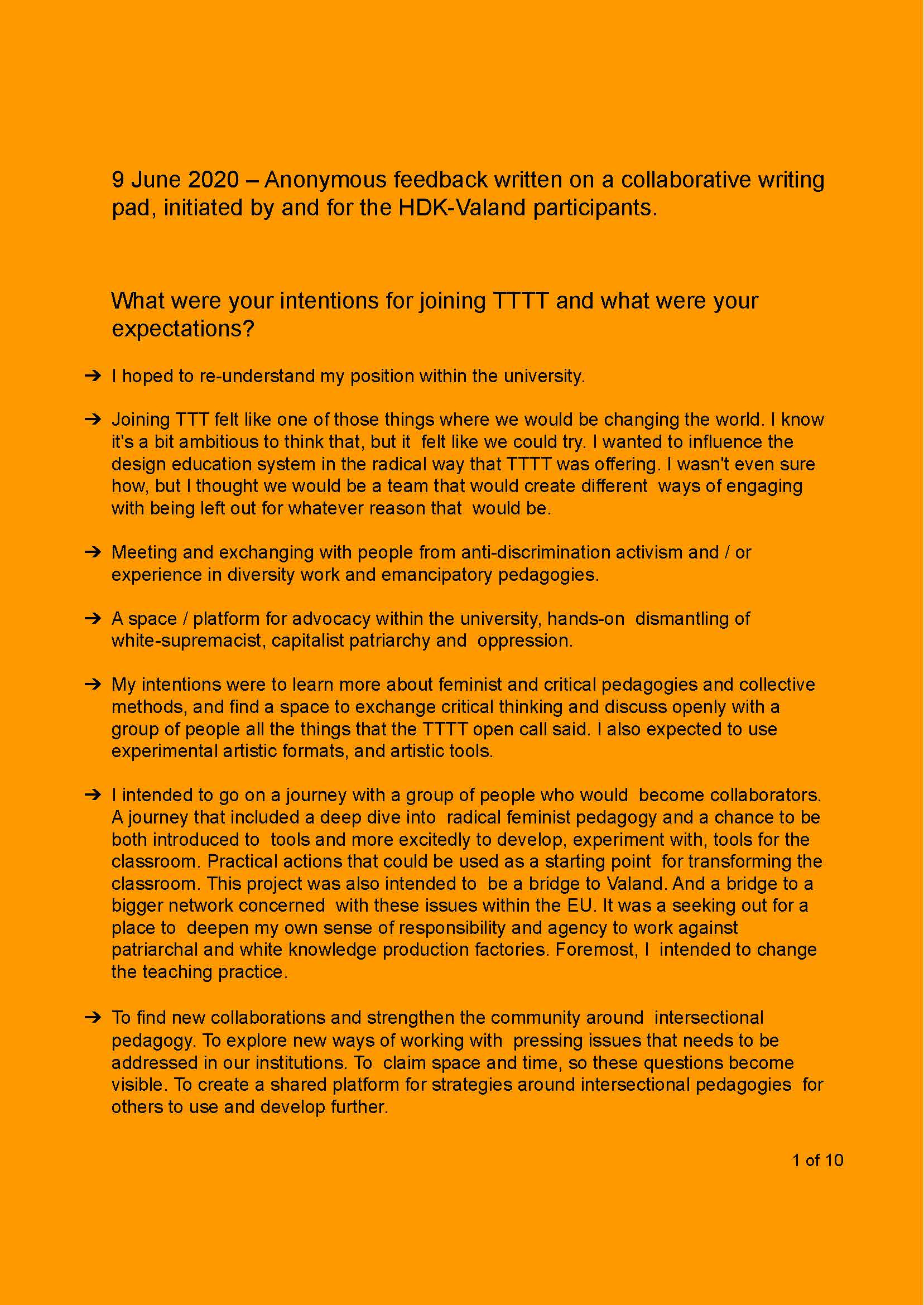

Anonymous feedback, Jun 2020

A second collective moment of reflection on June 9, 2020 was facilitated by members of the HDK-Valand group in Gothenburg, in the form of an anonymus feedback session using an collaborative writing pad. This feedback was guided by the following questions: “What were your intentions for joining TTTT and what were your expectations? How has it been feeling for you? What do you think is working? And what isn’t? What do you need?” Download PDF.

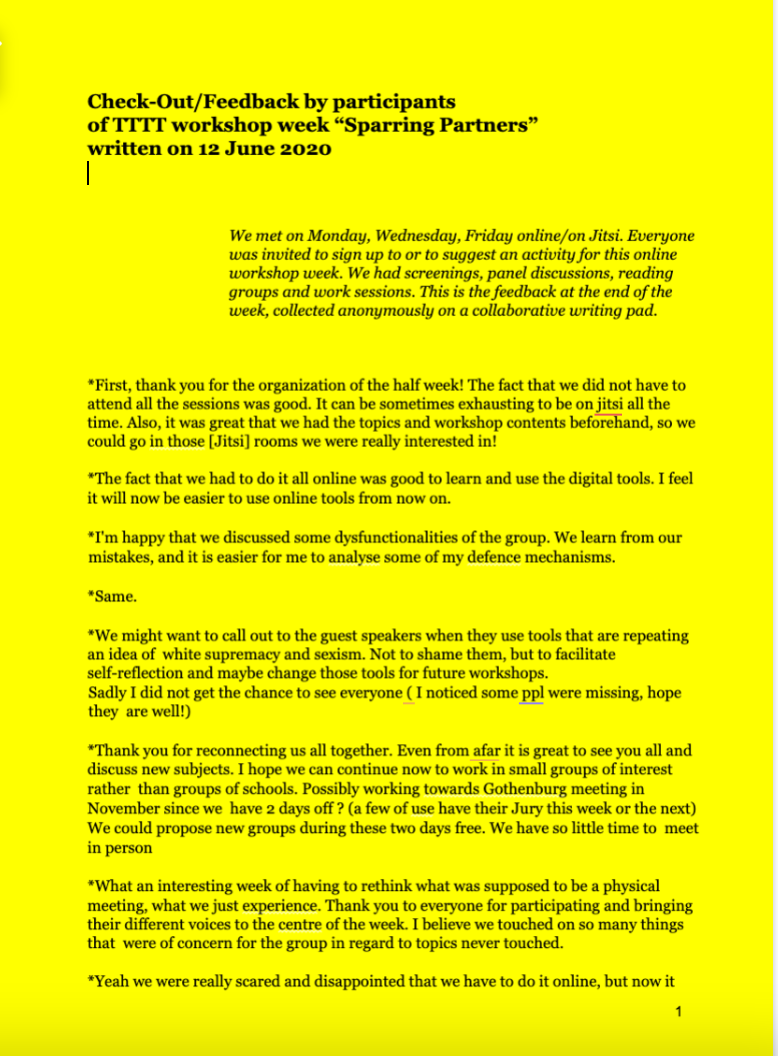

Checking-out, Jun 2020

Another check-out moment happened on 12 June 2020 the last day of the worksession «Sparring Partners» (8–12 June 2020) hosted by HDK-Valand and taking place online. This feedback was looking back at the week and forward to future meetings. Download PDF.

Friendly Peer Review, May–Jul 2020

The friendly peer review sessions took place in May and June 2020 for the working groups to get a fresh view and critical feedback on the works produced — from reviewers both inside and outside the project. These sessions were helpful as a method to share and discuss the resulting works with the group. The received feedback helped to make the individual pieces to be published on the online platform a welcoming and hospitable place for a future reader.

Reflection Workshop, Dec 2021

The Reflection Workshop took place on December 11, 2021 in Brussels and online. All 35 initial participants and organisers in TTTT (teachers, students and administrators) were invited to join. 20 participants, including some that had left the project, took part. Most of them met around a table at erg, others joined via the video conferencing platform BigBlueButton. The workshop was led by cultural worker Teresa Cisneros 1, who on the evening prior to the session had given a public lecture, “Undoing the institution: a person at a time”. The invitation e-mail included the outline of the workshop, and a set of questions that would be discussed.

The Reflection Workshop started with a short introduction round followed by a “grounding” that asked participants to share one compliment and one complaint about the project. It was also discussed how the recording and transcription would be used. A third part looked at participants’ expectations and their takeaways from the project followed by one-to-one recorded conversations, in which participants narrated an issue that had come up in the project, ways this issue had been resolved, and imagined alternative solutions. The workshop ended with a round of closing remarks from everyone present. One person that could not attend the workshop, responded by e-mail. Afterwards, all attending participants could correct the transcription, and leave comments. The transcription was pseudonomized and edited for clarity by the organizers, and by a copy-editor.

Reflection Workshop, Process

Schedule and Questions of workshop

Saturday, December 11, 2021

at erg and online

The following is a brief outline of the workshop on Saturday, as it can help us to prepare for our gathering. We will come together to share and reflect on our experiences. Therefore, we are sending you the agenda and the questions, so you can prepare.

By participating in this process we all agree to share our thinking, our honesty, our feedback. This will be used for future reflection that will inform a future type of publication (PDF, video, audio). The reflection will be anonymous unless we agree otherwise. We will ensure to share with you what will be created and get it signed off by you before publication.

- Hello / Open doors / Arriving / Breakfast 9:30–10:00

- Introduction, briefing, and time for questions 10:00

- Checking-in 10:15–11:00

Questions: Who are you? What do you hope to get from this workshop? What do you hope to give and how you are feeling?

- A moment of grounding 11:00–11:45

Questions: Can you give one compliment and/or one complaint?

- Break 11:45–12:00

- Reflection & Listening 12:00–13:00

Questions: What were the expectations? Where the group may not have met the expectations? Where things did go well? What do you take away from this experience?

- Lunch 13:00–14:00

- Discussion: 14:00–14:30

Questions: How to share the learnings of this encounter? (Which format or vehicle, i.e, transcription or recorded interview, etc.) What might be important to share? (Content or type of information, i.e., what happened in the process) And who would be interested to join the editorial team to work on this?

- Proposal: Sharing information through narrative interviews [one-to-one] 14:30–15:00

Questions: Can you recall a moment in the project when an issue/problem came up? Do you remember how it was solved? Can you think of other ways it could have been solved? (These interviews can be recorded and later transcribed to be shared and discussed.)

- Debrief & Closing 15:00–15:30

We met for this workshop both around a table at erg in Brussels and virtually, on the open source video conferencing platform Big Blue Button. We already had done the introduction and the check-in when we started recording.

Reflection Workshop, Summary

summarized by Femke Snelting

This summary is based on the edited transcript of the Reflection Workshop. It is meant for students, administrators, teachers, and others involved in (art)education that are planning to run a translocal project, or that want to do decolonial and intersectional work in and on institutions. It can hopefully help you anticipate issues and pitfalls, but will also remind you of the urgency and relevance of this work.

Expectations, urgencies and sustained commitment

. Participants (organizers, teachers and students) in TTTT each in their own way committed to decolonial and intersectional work on teaching and learning. They are keenly aware that a trans-European project across different institutional realities would be complex, but nobody doubts the relevance of the project itself. “We would be able to develop a kind of trust and generosity to learn from each other that would allow us to unpack difficult topics.”

.There are different understandings though of how to do the work. Some want to meet others who share the same struggle; others join TTTT for the opportunity to pay attention to processes and reflection. Multiple participants are motivated by the need and the possibility to make radical interventions into existing pedagogies, which they experience as racist and LGBTQ+-phobic. They expect the project to contribute to a change in institutional structures or to design practical pedagogical tools. “I hoped it would be a space of radical and somewhat vulnerable honesty and humility, a place of undoing and building collectively, figuring and building tools to help with the pedagogy around decolonizing – tools, basically, everybody was talking about.”

Things that worked out

“I was changed during the process”

. TTTT has provided participants with deeply transformative learning experiences.

“It was an eye-opener for me and all the materials, the people I met, and the thing I started structuring in my head, helped me a lot.”

. The project helped participants to focus, and to develop priorities for issues that they needed to address in their own practice. “I think that my teaching practice has shifted, hopefully forever.”

. This opportunity to experience different educational approaches was helpful, both personally and professionally, and the result empowering. “They were looking at what was supposed to happen and proposed what they saw could happen as well, not solely receiving, consuming, but actively participating.”

“I take away new relationships and knowledges”

. Throughout TTTT, participants have found occasions to exchange experiences, and listen to each other’s voices across different contexts. Even if many wish that they could have spent more time together. “It was really cool to gather and have a space for your voice to resonate and create and liberate creative energy from those experience of oppression.”

. TTTT constituted networks, communities, and collectives which shared experiences of ways that exclusions operate. “There were so many similarities within the marginalized experiences throughout the contexts.”

. The atmosphere was generally experienced as welcoming and supportive, and making an effort to open up to each others’ practice. “The amount of people who this project managed to get together and the amount of energy that was somehow there. I think that was amazing, and I haven't experienced things like that very often.”

“I learned so much in these small groups”

. The project functioned as a platform for different people to research together, partially due to the digital infrastructure created for the project. Learning happened often in the interstices between activities and groups. “The rubbing-off effects, or the in-between things that I've learned and picked up from listening to other people and working together.”

. Besides sharing materials and experiences, TTTT also provided learning about dealing with emotions and vulnerability as part of collective processes. “The small groups” are referred to as places where that work could be done best. They also gave participants working from different cities the necessary structure, which was important. “Thanks to this project I've learned a lot (…) It’s something that stays. It’s something that will stay with me for the rest of my life.”

“We finally created a tool, which we can all use”

. TTTT, as part of its mission to create a “toolbox”, indeed created and tested some urgently needed methods and devices. “I did have the experience of a trans*person (...) needing assistance with misgendering. And through this project, I was able to tackle it with them and that really quite drastically changed their experience.”

. Participants feel that the resources and pedagogical tools that they eventually created, are and will actually change things. “This was a very, very positive part of the whole project. I do know a lot of people in unions, equal treatment committees, and we can directly take the tool that we created into the institutions and possibly actually change some things.”

Issues and problems that have come up

“It was hard to find clearness when going virtual”

. The impact of the pandemic on a project that wants to work with complex collectivities across different institutional contexts, can not be overstated. Due to travel restrictions and other COVID-measures, two out of four workshops had to take place on-line. “It was hard to develop tools together, simply because we were not together and our computer screens were imposed as our main tool.”

. Participants struggled to find clarity and structure without being together in person. The “missing bodies”

seriously constrained TTTT in its potential for peer learning and collective research.

“This was really bigger than us”

. The obligatory size of an Erasmus+ project, and its administrative rigidity made it especially difficult for those not in the organizing team, to feel ownership of TTTT. “The project just became too big, too exhaustive, the way it was set up.”

. Participants felt that they could not constructively address representational issues, such as the Whiteness of the organizing team. Testimonies of abuse at one of the partner institutions resulted in a break of trust. 3 “There were little or no strategies of addressing the structures that exist at school. I think that there was this expectation that this group would be that, and they would all fight together in some way.”

. The scale and perceived immutability of TTTT seemed to be in the way of focusing on what participants felt they needed. “There were expectations that were not collectively decided, like intellectual outputs, that became the focus rather than a process of creating from the experiences and interests of everyone involved.”

“Can we really do all this work within the institutions?”

. The set-up of TTTT seemed to contradict a project that questioned power structures. The division between paid institution workers and students did not allow for horizontal organising, and also the project was read as pre-defined. “It was supposed to be an open and horizontal environment, but we received from the beginning clear instructions about what to do and how to do it.”

. At the same time, the openness of TTTT was confusing for some, because collective structures for decision-making and responsibility were missing. Without clear agreements, people were coming in and out as they liked. “There was this really difficult paradox of needing more meetings to set collective structures and on the other hand exhaustion.”

. While smaller groups succeeded in working through issues, sharing with the bigger group was much harder to do. “There were so many conversations and it was difficult to hold this common space.”

“There were a lot of conversations that were left halfway”

. Despite the shared desire to do so, TTTT did not always manage to create space for learning together from mistakes. “We didn't really know how … to debrief slowly, and to question our fragility or our toxic self construction.”

. Intersectional and decolonial work cannot be rushed. While it was felt important to connect with each other and each others’ contexts, it was also hard to make time for discussion and constructive re-organization, especially since all of this had to happen on-line. “We didn't have the tools or the time to create a collective story about what the TTTT network is.”

. For various reasons, a few participants left the project before it ended, for example because they felt trapped in a “complaint bubble”

. Some of the ones that stayed in the project signalled that racialized people stepped out because “they were busy with other emergencies than taking care of like, white fragility things.”

. Friendly peer review sessions invited proposals and to mitigate some of the project’s issues. These sessions were generally regarded as constructive, but only a small group participated.

“A contradiction between the rhetoric used and our ways of operating”

. Making time for working through difficulties, meant less time for concrete work. Even if the focus on tools was being reconsidered from the start, they experienced that the practical aspect of creating and experimenting with them, received less attention than hoped. “The initial plan was to create tools and to try them in reality, so every day in schools and so. And I found that we talked a lot about things, but I miss the practice and the fact to create those tools and to use them.”

. A balance between theory and practice, probably also related to going on-line, was not always found. On another level, questions are asked about whether the project managed to practice what it promised. “I’m wondering whether it really is, or to what extent it really is, a contribution to the struggles that we are referring to.”

Recommendations and takeaways

The following takeways and recommendations have been summarized from suggestions that participants made in the Reflection Workshop, based on their learnings from TTTT. Of course, these are easier said than done! “I’m actually hopefully embarking on a new European project and what I’ve learned here will be a starting point to not reproduce the mistakes and take with me the good parts of it all.”

Framing of the project

- Get to know partners well before starting such a large-scale project.

- Be mindful about who is starting a project, and who can be held responsible. Good intentions are not enough.

- Choose four partners if you need three, just in case. Otherwise, keep the project as small as technically possible.

- Be inclusive, but avoid tokenism; make sure people of color, queer, transgender and people with disabilities take part in writing the project, are in the organizing team, and participate (students and teachers). Make sure that all partners do the same.

- Use words such as “decolonial” and “intersectional” with care. It is urgent to engage with these practices, but harmful when a project has no way of doing anything about oppression in their own institutions.

- Try to find a balance between formulating a project that has space to (re)define elements collectively when needed, but which is focused enough to not take on the world.

Legibility of resources, roles and responsibilities

- Find a way to unpack the structure of the project early on. Go through the budget together. What parts are immutable, and what parts can or need to change?

- Create common access to relevant administrative documents for everyone involved.

- Recruitment processes should work the same way in each participating institution. If that is not feasible, make sure differences and expectations are legible from the start.

- Be clear about power relations, by making the different roles and responsibilities of each person as transparent as possible. Avoid terms such as “horizontality”.

- Try to be clear about what results are expected (if any), what criteria need to be fullfilled, and what space for manoeuvre there might be.

- Take time to make agreements (social contracts) about how to work together.

- Include ‘trusted persons’ as part of the roles in the project. Maybe have a permanent workinggroup for check-ins, and following up with people that drop-out or have to step out temporarily.

- If publishing is involved, form an editorial workgroup early on. Decide together how they decide what gets published, for who, and how publications are mediated.

- Follow up with people that leave the project, and feed this information back to remaining participants. Who are they? Are they OK? Why did they leave? Any patterns?

- If addressing problems, it is important to try and contextualize issues as precisely as possible, and also to not take critique personally.

- Help out with listening for problems that are brought up by others, and ask attention for them.

- Clearly communicate with each other about ways that issues, complaints and problems are being followed through (also when nothing can be done).

Modes and methods

- Make small working groups part of the structure, with some autonomy and budget so they can take responsibility.

- If a project feels for whatever reason exhausting, pay special attention to what this might do to already marginalized participants.

- At shared meetings and events, leave space in the schedule for adhoc, self-managed activities.

- Pay attention to emotions, listen to each other's lived experiences. Be gentle, not defensive.

- Create brave spaces where fragility is welcomed, and commit to a feminist ethics of care.

- Reflection is important, but needs to coincide with practice and experimentation.

- Organise regular Friendly peer review sessions to allow participants to come up with proposals and to mitigate issues.

- Don’t be bombastic with beautiful words. Simplify your language if possible.

- Differences are a strength. Everybody has different experiences, everybody has things that they don't understand. Provide support for translation, and learning together.

- Provide Open Source digital infrastructures for collaboration, communication and archiving.

- Involve participants in the activation of project outcomes.

- Allocate common, public spaces for participants so they can share resources with their own institutions (both physical and digital).

- Never underestimate the impact of “going on-line”.

-

Teresa Cisneros is a Chicanx Londoner. Originally from the Mexico-Texas border, “La Frontera”, she practices from where she is from, not where she is. A curandera and arts administrator by choice, currently she is Manager in Culture, Equity, Diversity Inclusion at Wellcome Trust but thinks of herself as a "curator of people.” ↩↩

-

Femke Snelting is based in Brussels and develops projects at the intersection of design, feminisms and free software. In various constellations she has been exploring how digital tools and practices might co-construct each other. She is committed to organising for and with complex collectivities. ↩

-

See Open Letter TTTT responding to the harassment cases at ISBA. Download PDF English. Download PDF French ↩